By Peter Tonguette

If you’ve ever read Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s classic book “All the President’s Men” — or seen Alan J. Pakula’s acclaimed 1976 film adaptation starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman — you may think you know a thing or two about Watergate. You surely have a sense of the basics: In a misbegotten attempt to assure President Richard Nixon’s re-election in 1972, a cadre of crooks broke into the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate building in Washington, D.C. They were caught, and Nixon, under pressure about what he knew, resigned in 1974.

If you’re of a certain age, maybe you even watched the Senate Watergate Hearings on TV, which introduced the viewing public to some of “the president’s men,” including White House officials John Dean, H.R. Haldeman, and John Ehrlichman.

Picture editor Grady Cooper — one of the editors to work on the new HBO limited series about Watergate, “White House Plumbers” — remembers his own mother being absorbed in the real-life drama unfolding in the nation’s capital.

“I’m at the age where, when I was growing up, I would come home from school and my mom — my parents were very staunch Democrats — was glued to the Watergate hearings,” Cooper said. “She watched it gavel to gavel. She could be on the phone with her friends and screaming at the TV: ‘I can’t believe they did this.’ I very much knew about Watergate from growing up.”

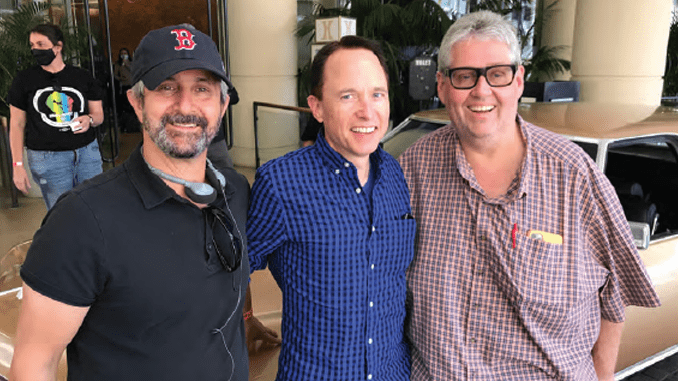

Cooper and his colleagues — picture editors Erick Fefferman, Roger Nygard, ACE, and Steve Rasch, ACE, who split the episodes or worked in various combinations — came to know much more about Watergate while working on “White House Plumbers.” The five-episode series, which will premiere in March, shines a spotlight — or should we say the interrogation lamp? — on the two men most responsible for stage-managing the Watergate break-in: former CIA officer E. Howard Hunt (Woody Harrelson) and Committee for the Re-Election of the President official G. Gordon Liddy (Justin Theroux). Co-starring in the series are Lena Headey as Hunt’s wife Dorothy; Domhnall Gleeson as John Dean; and Ike Barinholtz as Jeb Stuart Magruder. (Assistant editor Jon Mechen co-edited several episodes.)

More than five decades after Watergate, Hunt and Liddy’s plotting, planning, and law-breaking can come across as darkly humorous, but director David Mandel emphasized the unique mix of comedy and drama that came to define the show.

“‘White House Plumbers’ has a very unique tone,” said Mandel, also an executive producer and showrunner of “Veep.” “It’s not a comedy per se, but at the same time, the Watergate break-in and these characters like Gordon Liddy are very funny. I knew the show would have to find its own unique tone and that there would be a lot experimentation in the edit room to figure out where that line was.”

The picture editors describe the process of defining — and then finding — the tone as a continual challenge.

“David was experimenting with every moment: ‘Can we push this for comedy? Do we get more impact in this moment if we pull back off of that instinct and let it play for drama?’” Fefferman said. “What we discovered, which is not unusual, was that if you let it play straight, it ends up having more impact — and is also more humorous.”

In general, then, material that was highly comedic fell by the wayside for material that was more dramatic. “The comedy was slowly milked out of it,” Rasch said. “The broader stuff came out, although there are still a few pieces like that. But the series became more consistent once we did that because some episodes didn’t have a lot of broad comedy. The show evened-out as the cuts went down.”

Added Cooper: “Our natural instincts were to lean in toward the comedy, and then slowly we were like, ‘Wait, the comedy is better if there’s more drama to it.’” In fact, Episode 1, edited by Nygard and Fefferman, unfolds like a family drama. The audience is invited into the private lives of Hunt and Liddy. We see their struggles, their hang-ups, their disappointments — all the things that made them ideal candidates to later commit crimes on behalf of Nixon.

In the case of former CIA officer Hunt, Nygard said, “He was down on his luck and looking for a job, and somebody throws him a bone: ‘Hey, we need somebody to do something a little shady.’” Nygard added: “He’s hungry to get back into the political world where there’s some intrigue and power and excitement.”

“There was a mix of tensions that were pulling at these guys from within their work and home lives that resulted in them making poor decisions that would snowball into this notorious event in American history,” said Fefferman, who said the series then shifts into a “bromance” between Hunt and the equally desperate Liddy, a former FBI agent.

“It was both a budding bromance and a rivalry at the same time,” Fefferman said. “They both knew their careers and personal destinies were tied to one another, for better and worse, yet they were still jockeying for position while in pursuit of the same goal.”

Added Cooper: “These characters are very patriotic, but you know they’re flawed, and as the show progresses, it gets darker and darker in tone.”

The chaos culminates in Episode 3, edited by Rasch with additional editing by Fefferman, which depicts not one but multiple attempted Watergate break-ins before the burglars overseen by Hunt and Liddy are successful. “After doing a lot of research, they found it was four attempts because of bumbling, pretty much — they couldn’t get into the Watergate,” Rasch said. “I didn’t have a lot of story. I had mostly this bumbling bunch of Cubans trying to get into the Watergate, and it was very much a pleasure to cut.”

‘Editing is like bending metal with your hands. You can’t do it, but you have to do it. You keep squeezing and shaping.’

Fefferman said that part of the challenge on Episode 3 was making sure the audience could understand the machinations of the break-ins. “In the telling of it, at times it got confusing to us!” Fefferman said. “We often had to ask one another, ‘Wait, which attempt was that?’ . . . But once the mechanics of this consulted timeline was laid out, we could start to hang all the set pieces on there. As confusing as it could be, we needed the audience to be able to clearly track how these guys put themselves in position to get caught.”

The editors had no shortage of footage to experiment with during the process: Mandel is known for experimenting on the set and delivering plenty of options — or challenges — to the editing team.

“Dave Mandel tries things on the set,” Nygard said. “He tries a lot of jokes, complicated angles, and challenging ideas, and then we figure it out.” Mandel and director of photography Steven Meizler often delivered scenes covered with inventive, aggressively styled, and over-the-top camera angles. “We’ve got to find the solution even though we maybe don’t have the coverage that we wish we had or Dave wishes he had,” Nygard said. “He will work at it until he finds a solution, and it’s not easy. But it’s really rewarding when you get there.”

Sometimes, problems were presented by Mandel’s preference for one-ers with Harrelson and Theroux, two very different actors who work at different speeds.

“Justin is a very precise actor and he comes in very planned with an agenda of his own,” Cooper said. “Woody — in a very interesting way, because he comes from comedy but he’s become a great dramatic actor — kind of just feels it and goes with his instincts.” Consequently, one take might be Harrelson’s strongest while another might be Theroux’s. “In the editing room, even though Take 7 might have been circled, you realize you need to cut away halfway through because of a flub or a bad pause or something that wasn’t apparent on the set,” Rasch said. “Now you start doing editorial tricks to try to shorten the scene or get in later.” Sometimes rewriting was done via loop lines and ADR.

“David Mandel once said to me that editing is like bending metal with your hands,” Nygard said. “You can’t do it, but you have to do it. You keep squeezing these scenes, and squeezing and shaping, until you get it where you need it to be.”

Maybe the same analogy applies to the series as a whole: Whether from distant memories of the Watergate TV hearings, or a more recent viewing of “All the President’s Men,” many viewers will have their minds made up about the scandal. But “White House Plumbers” seeks to explain, not excuse, the psychology of two men central to the scheme, Hunt and Liddy.

“The show wasn’t trying to elicit sympathy for these guys, or try to get you on their side, because their political positions and their ethical perspectives obviously weren’t great,” Fefferman said. “But we at least wanted to show that there was a human side that influenced how they behaved and the choices that were made.”

“Antagonists are just as real as protagonists,” Nygard said. “They have families and lives.”