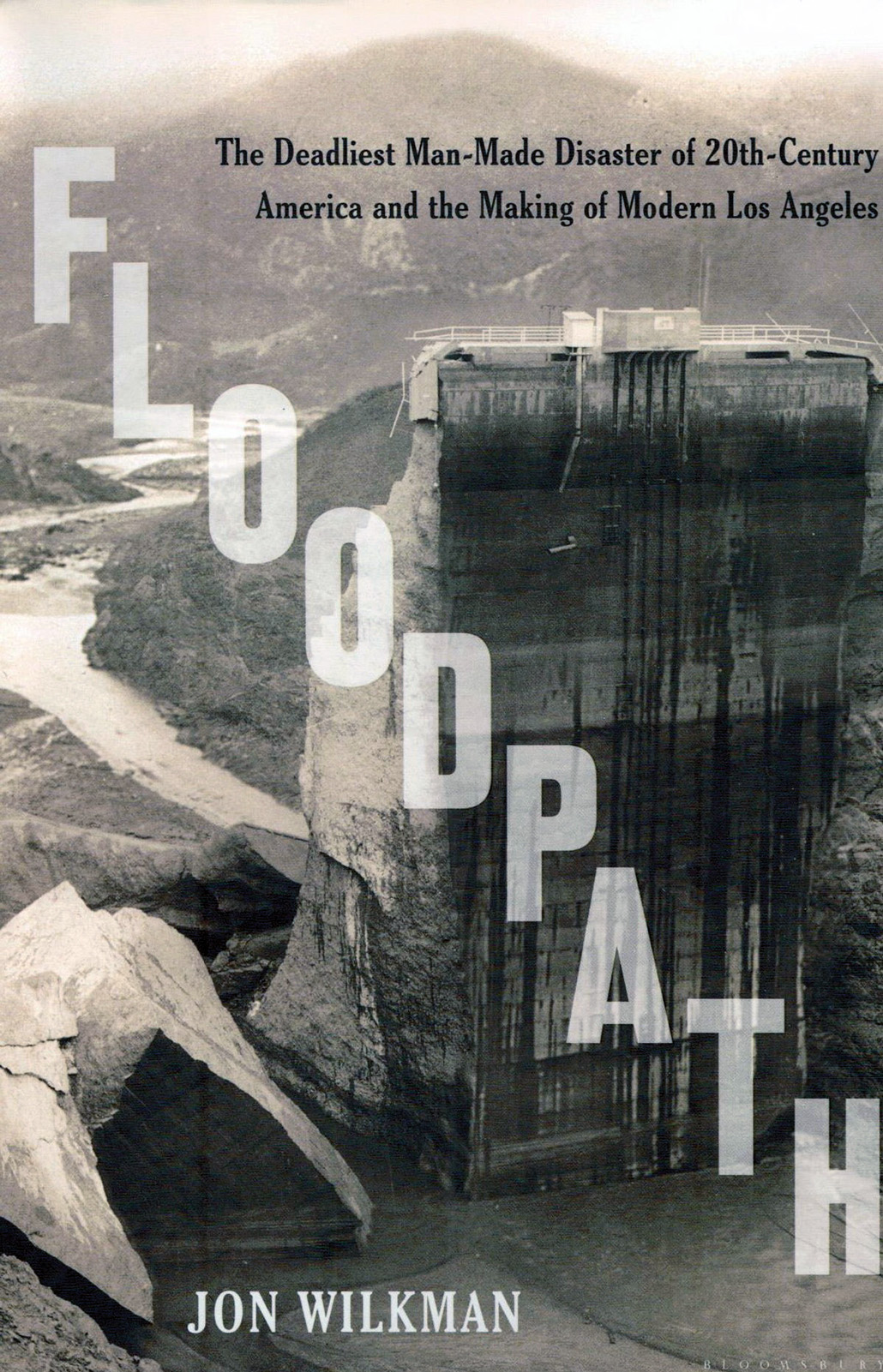

Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles

by Jon Wilkman

Bloomsbury Press

Hardback, 326 pages, $34.00

ISBN # 978-1-62040-915-2

by Betsy A. McLane

At a preview screening of the film Chinatown in summer 1974, an official from the City of Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is reported to have remarked, “It’s totally inaccurate! There was never any incest involved!”

That anyone employed by the DWP might quip that the corruption and villainy portrayed in the film is true reveals how deeply the history of Los Angeles is tied to its endless demand for water. The film is set in the late 1930s, and the events that inspired it — the so-called California Water Wars of the Owens Valley — actually took place primarily between 1902 and 1928. Such mixing and mashing of facts and fables, timelines and personalities is what makes Hollywood myths, and Chinatown, produced by Robert Evans, written by Robert Towne and directed by Roman Polanski, offers the screen’s greatest mythic vision of Los Angeles. All were nominated for Oscars and Towne won Best Original Screenplay. Behind the neo-noir atmosphere and twisted characters of Chinatown is a true story, even more complex and deadly than Towne’s, but few remember it today.

In Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles, Jon Wilkman does a masterful job of culling fact from legend. His focal point is the St. Francis Dam break of 1928 and the resulting floodwall that swiftly and terrifyingly killed hundreds in Los Angeles and Ventura Counties. Few people now think about the disaster, although the former dam site is not far from the thousands of vehicles traveling every day on Interstate 5 near Santa Clarita. The dam was masterminded and supervised by self-taught engineer William Mulholland — Hollis Mulwray in Chinatown, portrayed by character actor Darrell Zwerling as a champion of good who is murdered because he wants to stop the building of another dam that might also break.

The real Mulholland was far more complex, more of a combination of the Mulwray and Noah Cross (John Huston) characters in the film, sans the incest. He not only designed and supervised the building of the “monster” San Frisquito Canyon dam, he was directly responsible for envisioning the entire water supply for a booming Los Angeles, including Lake Hollywood and the revolutionary, gravity-driven Owens River Aqueduct. LA still uses his aqueduct.

The real Mulholland was far more complex, more of a combination of the Mulwray and Noah Cross (John Huston) characters in the film, sans the incest. He not only designed and supervised the building of the “monster” San Frisquito Canyon dam, he was directly responsible for envisioning the entire water supply for a booming Los Angeles, including Lake Hollywood and the revolutionary, gravity-driven Owens River Aqueduct. LA still uses his aqueduct.

Mulholland arrived in Los Angeles at age 22 in 1877, worked initially cleaning ditches and ultimately became the Chief of the Bureau that became and remains the all-powerful LADWP. His rise parallels that of the city from small town to major metropolis. The ballyhooing of civic leaders, then and now, who promote a sun-filled, shiny future as they profit from real est

ate speculation — from Hollywoodland in 1923 to Playa Vista today — could not exist without Mulholland’s passion for water. He and the movie character Mulwray share that passion, and it proves to be the undoing of both. Mulwray is found drowned in one of his own reservoirs; Mulholland publicly accepts the blame for the Saint Francis disaster and is forever shattered. It is no wonder that in Polanski’s anamorphic vision, local history is obscured by layers of smoke and the low-key Oscar-nominated lighting of cinematographers Stanley Cortez, ASC, and John Alonzo, ASC.

Just as the sound design in Chinatown uses a finely mixed refrain of dripping, bubbling and running water, Wilkman’s research is thorough and meticulous. He carefully organizes and presents thousands of details. An off-screen comment about Mulwray in Chinatown (“The guy’s got water on the brain”) certainly applied to Mulholland — and can also be said of Wilkman, an experienced chronicler of Los Angeles history. He is the co-author of two pictorial books about the city and is the producer/director of several historical documentaries, including Moguls and Movie Stars, a TCM series about American movies.

The often-disputed facts and colorful tales surrounding the dam failure have obviously been an obsession for Wilkman for years. Was it an earthquake, angry ranchers with bombs, faulty dam design, or low-grade, cheap cement that created the disaster? He considers these theories and, along the way, makes valuable contributions to California history in the form of interviews with some who remembered the flood, including Mulholland’s granddaughter and biographer Catherine. Those interviewees are dead now. W

ilkman allows them to speak and counterpoints their personal stories with research from newspaper archives, official reports and government documents, books, articles and scholarly theses. He also recruits expert observations from the sciences of engineering, water management, geology, seismology and dam building. All of this makes for fascinating reading that only occasionally — primarily in the book’s last quarter — becomes more dry than entertaining.

While Wilkman is excellent at painting portraits of the many men who both supported and decried Mulholland and his plans, their names and changing titles sometimes get confusing. A useful map of the flood area brackets the book on the insides of its cover, but a list of who’s who among these characters and when they did what would have been a useful addition. It is sometimes necessary to refer back and forth to be precise about events. The final chapter, “After the Fall,” in which Wilkman reveals the most current computer-modeled theories about why the dam collapsed (do not peek ahead and spoil the story), becomes a bit preachy, but this in no way detracts from the excellent research or the page-turning drama. There are also enough photographs to provide visual context.

The author uses his vast array of primary resources to make several observations about the St. Francis Dam disaster that resonate today. One is that water and energy have always been and remain chief concerns in Southern California, and that our need for these has radical impact on the environment and on people’s well-being. Another is that haste and pressures to save money may be in the interest only of certain individuals; in other words, we need always be on the lookout for possible corruption. A third point is that it is the poor and people of color who bear the greatest misfortune in a disaster — man-made or otherwise. In 1928, many of the flood victims were Mexican farm workers who lived in low-lying camps along the Santa Clarita River; many remain among the unknown dead.

As private detective Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson in an Oscar-nominated role written expressly for him) investigates Mulwray’s murder, he is drawn under the dry LA River’s Hollenbeck Bridge. Here lived a local drunk, who died from drowning, providing a clue about the mysterious presence of water during a drought. In today’s Los Angeles, it would be the thousands living in homeless encampments that die in a torrent. And in perhaps the most timely point, the unchecked hubris of one individual and his political supporters (whomever they may be) can only lead to tragedy.

Looking back to understand the present may not be a strong point of Southern California’s culture, but Wilkman makes its history meaningful in a way that demands our attention today. He may regret the obfuscation of fact by the compelling mythmaking of Chinatown, but the film is brilliant in its historical complexity. Wilkman painstakingly dissects the debate between populists and private corporations over government-sponsored public works projects in the 1930s. Polanski and company capture the essence of that debate in a courtroom scene in which a giant portrait of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt looms as Gittes listens while city leaders rousingly endorse the new dam, and Mulwray refuses to build it.

Floodpath and Chinatown each offer insight, and the reader is well advised to experience both.