by Peter Tonguette

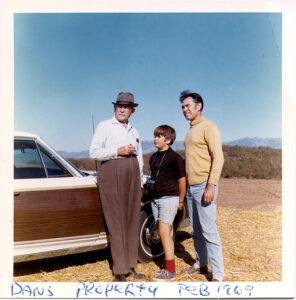

To those who knew him best, film editor Philip Cahn, who was born June 18, 1894, in New York City, was not a rabble-rousing sort. As his grandson, editor Daniel Cahn, A.C.E., remembers, “He always wore a hat. He always wore a tie. Casual for him was the hat, the tie, the slacks — but without the jacket! He always came across as a very gentle, quiet, low-key and subtle human being. As I got to work in the business in the 1970s, I would meet people who had worked with my grandfather and they would always tell me what a gentleman he was.”

Yet it was Philip Cahn who, along with fellow film editors Ben Lewis and I. James Wilkinson, took the bold step 75 years ago of founding the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors (later to become the Motion Picture Editors Guild). In a remarkable twist of fate, his grandson Daniel, who was elected President at the end of 2010, presides over the Guild’s diamond anniversary this year.

If there is such a thing as a motion picture family who has been touched by the hand of destiny, the Cahns are it. The son of Philip and father to Daniel is Dann Cahn, A.C.E., the legendary editor of I Love Lucy and dozens of other classic television programs.

Besides the trio of Philip, Dann, and Daniel, other editors in the family include Philip’s younger brother Edward (later to become an accomplished director) and his brother-in-law Leon Barsha, whose credits included the acclaimed Kirk Douglas Western drama Lonely Are the Brave (1962), and who also became a producer and director. “It was quite a family,” Dann recalls. “No one was reticent and everyone was pretty strong-minded. In the early silent days, when the work was finished at the end of a Saturday, what would they do but pack up a projector and bring it over to our house and run movies at home. That’s how I grew up.”

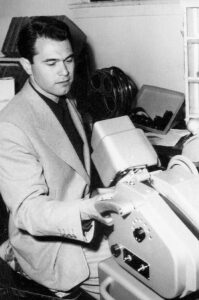

The plan was never for an editing dynasty. “My grandfather owned property out by Universal Studios and he raised chickens,” Daniel says. “But the chickens died [because the power went out], so he went to work at Universal.” Philip enjoyed a prolific career at the studio. Perhaps the high point of his time there was cutting the 1934 John M. Stahl version of Fannie Hurst’s Imitation of Life, starring Claudette Colbert. Because Philip was associated with such a successful film, Dann recalls, “They gave him a picture to direct. It was I’ve Been Around [1934], with Rochelle Hudson and Chester Morris. Well, it was a bad script and all of the other directors had turned it down.”

So it was back to the cutting room for Philip Cahn. As prolific as ever, he picked up where he left off at Universal. The year before he co-founded the Society, he edited Sutter’s Gold (1936), an epic about the California Gold Rush. It is one of Dann’s favorites among his father’s films. “The picture starred Edward Arnold and Lee Tracy,” Dann says. “That was one helluva picture. It really told the story of California. They shot it here and they actually

dammed the Los Angeles River up and it looked like northern California.”

That Philip was helping to organize editors during this demanding period of his career is, in Daniel’s view, only logical. He speculates that there was no high-minded notion behind founding the Society, but it arose instead from very practical concerns similar to those of today. “People were working night and day,” he says. “The work conditions were very poor. I just think they were the ones who spoke up.” Adds Dann about his father, “His thinking was that the Screen Directors Guild was forming at the time and that the editors should follow suit and get strength and have representation. And they did it!”

During World War II, as Dann was serving in the First Motion Picture Unit, Philip also contributed to the war effort by editing several of the most successful Abbott and Costello comedies. “He did three in a row,” Dann says. “We were going to war and they did Buck Privates. That was immediately followed by In the Navy and then Keep ‘Em Flying [all 1941], so they covered the three forces.” Philip’s other Abbott and Costello comedies were Hold That Ghost (1941), Ride ‘Em Cowboy (1942), In Society (1944) and The Time of Their Lives (1946). In the late 1940s, Philip went independent, collaborating with Samuel Fuller on several of his most iconic pictures, including The Steel Helmet (1951) and Park Row (1952).

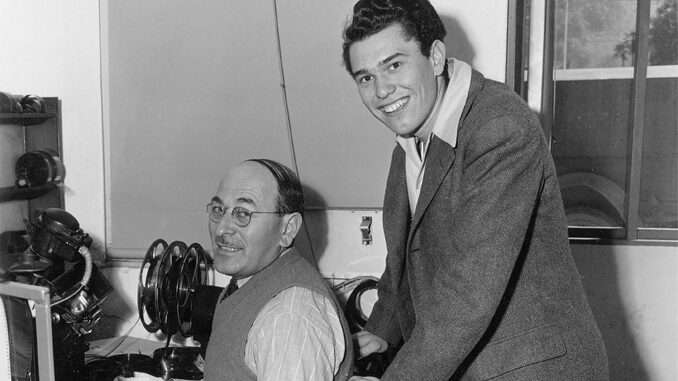

By this time, Dann had bounced between jobs in the industry in which he had grown up. He was a child actor before following the rest of his family into editing. He honed his craft in the First Motion Picture Unit. “I was a full-fledged editor when I came out of the service,” Dann says. “It was like having a four-year college career.” A spell as an assistant editor included some impressive credits — such as a year-long stint working with Orson Welles on the director’s brilliant version of Macbeth (1948) — but he wasn’t going to be an assistant for long. It is a cliché to say that fate came knocking, but it really did.

As Dann recounted in an article he wrote in CinemaEditor magazine, he was working on a picture called The Lady Says No (1951) when his old friend William Asher “stuck his head in my cutting room… He told me that he had just turned down a job to cut a new series with Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. He said the producer/head writer Jess Oppenheimer was looking for someone to edit the show, to be called I Love Lucy.” The job was Dann’s. He eventually became Desilu’s editorial supervisor; Bud Molin (who Dann first met on Macbeth) then took over as the show’s editor. Asher ended up joining them for the second season, but as a director rather than editor.

Shot on 35mm film with three cameras and edited on the famous Moviola dubbed the “Three-Headed Monster,” I Love Lucy (1951-57) was the beginning of so many new things, and Cahn was present at the creation. “Television was a live medium related to radio,” he says. “We brought it into the perspective of the motion picture. The rhythms and tempos of filmmaking were applied to television. One of the big contributors to that was [director of photography] Karl Freund and the creative staff at Desilu.”

Other innovations were of a more practical kind. “My dad tells the story of when they were using light flashes to sync all of the cameras,” Daniel remembers. “So he walked down to the mill and had a giant four-foot slate made! It was a common marker for all of the cameras to focus in on and clap.”

“When you’re young, there are nothing but challenges,” Dann says. “And you jump right in. There’s no fear to try new things.”

Daniel comments, “My dad got on one of those things that’s special — actually, it was the show that was the most special ever. It just doesn’t happen that much.” It is true — while Dann’s later series included such hits as The Beverly Hillbillies (1962- 71) and Police Woman (1974-78), as well as features for directors as diverse as Russ Meyer and Richard Fleischer, few things in any career could top the immortality he achieved with his first big editing job.

What price television? For Dann, the success of I Love Lucy brought him an avalanche of work as Desilu’s editorial supervisor, but not more feature work. Daniel says, “I recently found a Variety blurb from 1953 saying that Desilu post- production is managing more shows than any other studio at that point.” But if Dann never achieved the same notoriety in features that his father had, he became a trailblazer on the small screen. He even introduced his father to the new medium. Philip’s first series was Desilu’s The Lineup (1954-60) and he soon began an eight-year run on The Loretta Young Show (1953-61).

“He had done several big war movies for producer Walter Wanger, one of which starred Loretta Young,” Dann says. “Strangely, I wound up as the supervisor on The Loretta Young Show. She said, ‘Are you related to Phil Cahn?’ I said, ‘Yes, he’s my father.’ She said, ‘I loved your dad.’ I said, ‘Well, he’s available!’ But he was used to having control of his cutting room. We had all of these network guys that wanted to be in there and control things, as it is today. Some of our top editors had two or three production executives with them in the cutting room. It drove us nuts. But Loretta said, ‘Leave Phil alone.’”

“I know my grandfather was loved by Loretta Young,” Daniel adds. “He has loosely been referred to as ‘Loretta’s editor.’ They enjoyed a very long relationship. Even that is unusual — that an editor and a star would have such a relationship that the star would demand who the film editor is on the show. But that came under the auspices of my father’s department, and he has told me, ‘Your grandfather worked for me. At the end of his career, I brought him in to work on the show.’” Philip Cahn died September 28, 1984, in Thousand Oaks, California.

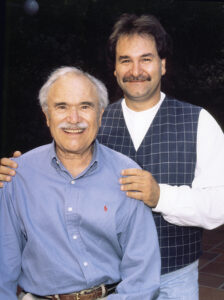

Dann always had a magnanimity toward those in his profession. Think of the countless opportunities he gave

to up-and-coming editors. Perhaps his most famous protégé is Michael Kahn, A.C.E. — the man who became the closest collaborator of Steven Spielberg — who was at one time Dann’s office manager at Desilu. Dann laughs, “He was as far from the cutting room as you could get.”

Daniel remarks, “My father is the type of person who does nice things for people. He always fought for the people who were underneath him. He always moved all of his assistants up. He never did anything with the expectation of getting anything in return.” In Kahn’s case, however, he was able to repay Dann’s kindness. He mentored Daniel early in his career, inviting the young assistant editor to work with him on Spielberg’s World War II comedy 1941 (1979). “I was nowhere close to being experienced enough to work for Michael,” Daniel says. “But I finished being experienced enough. Michael was demanding, but I really learned to edit by assisting him — handing him film trims and grease pencils and listening to Steven and him work. I was hooked.”

At any given time during the last eight decades or so, a member of the Cahn family could be found toiling in a cutting room somewhere. They have witnessed first-hand how their trade has evolved, particularly when it comes to technological advances. “The business that I came into is the business that my family knew,” Daniel comments. “All of the revolutions have happened in my time. Everything that I know has changed, particularly in the last 10 years.”

Daniel sees a transition on the horizon not unlike the one his father faced — from features to television — in the early fifties. “I am seeing the end of film,” he says. “I am seeing an entire workforce of laboratory workers coming to an end. It’s strange that cameramen are now getting caught up in the technology that we’ve been dealing with for 25 years.”

At the same time, Daniel believes that the fundamental art of film editing — storytelling — remains the same. “If they returned to making pictures on Moviolas tomorrow,” he says, “I honestly think that my father could go in and edit. He could grab rolls of film and put them together… There is something to be said for the Avid or any of the other systems. It really frees the editor up creatively. But true editors could go back and cut on film right now. They were trained in storytelling. It took skill to learn how to manage film and handle it. It was like working with clay or paintbrushes.”

Daniel sees parallels between what the Editors Guild membership faces today and the conditions his grandfather encountered 75 years ago. Then, as now, “There is an anti-labor attitude,” he explains. “It’s in a business that generates a lot of money, but in my mind, there is enough to go around. I do not find the crews being responsible for pictures being over-budget and over- schedule.”

He believes that the legacies of his father and grandfather give him a unique, even one-of-a-kind perspective, and indeed they do. In the end, though, it is not Daniel’s famous last name and all of the movies and shows we associate with that name that inform his mission as President of the Guild. Instead, it is his own experiences: “I worked for people who insisted that you work all night and all day without getting paid overtime.

I worked non-union and I really regret some of the mistakes that I made in my choices of what to do. I brought myself back into a frame of mind that was very much what my grandfather was like.”

For three generations, the Cahn family has so frequently been at the right place at the right time. In Daniel Cahn, the Motion Picture Editors Guild is fortunate to have the right man at the right time. As he says, “Wherever he is, my grandfather is probably getting a kick out of this.”