by Rob Feld

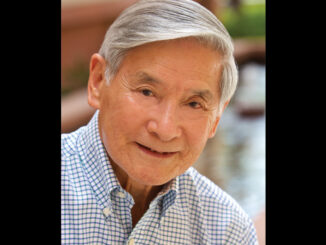

Adam Gough, ACE, started making short films as a teenager with his friends, in Hampshire, England. There he found a passion for editing, eventually studying film at Solent University in Southampton.

“It was the part of the filmmaking process that I felt I had most control over, and was the most creatively rewarding,” he recalled.

The first opportunity he found after graduation was in the cutting room of a film called “Stormbreaker,” which led to his first paid position as an editorial trainee on “Children of Men.” From there, he worked his way through assisting and visual effects editing until he got his break, cutting a documentary on Keith Richards that is being directed in an ongoing fashion by Johnny Depp.

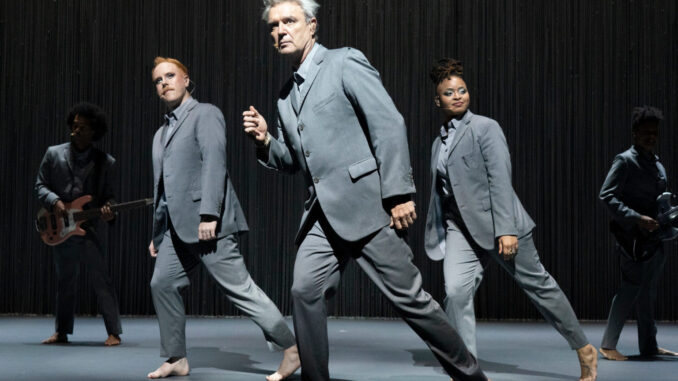

Gough won much acclaim for his work cutting “Roma” with Alfonso Cuarón, and he is now seeing the HBO release of David Byrne’s Broadway production of “American Utopia,” directed by Spike Lee. The concert presents Byrne’s classic songs on a bare stage with his band fully mobile, their instruments strapped to their bodies if necessary, so that they can follow choreography around the stage and through the audience.

Three live performances were filmed, giving Gough a tremendous amount of footage—the first was shot with 11 cameras, the second with 10 cameras, and the third covered specific songs with five cameras (including Steadicam and crane). The band was additionally filmed biking through New York City for the end credits. Ultimately, between the three performances, each song was covered by at least 21 cameras, and possibly up to 36. Using the mass of footage to its best advantage called on everything in Gough’s toolkit, to smoothly trace the film’s theme of human unity.

CineMontage: Your past experience includes some particularly effects-driven movies. How do you think that influenced and informed your craft?

Adam Gough: My career path through assistant editing and visual effects editing on larger films taught me more of the toolbox to utilize as an editor. I will use splits, re-speeds, morphs over jump cuts to get the most out of a performance when necessary. There are even shots in “American Utopia” where I used visual effects to splice different performances together to improve the shot. This was usually to fix a lighting issue or a choreography stumble. I love those types of invisible effects fixes. I generally prefer a more invisible edit, but I must admit I’ve been enjoying making bolder cuts and larger statements in the edit in my work with Spike.

What was your apprenticeship experience like, and what was the most useful thing you learned from a mentor?

A large part of my development in film came from mentoring, even if I didn’t realize it at the time. I started as a PA in cutting rooms and worked my way to editor through assisting. As an assistant, I was very lucky to work with and learn from incredible editors. The advice I had from Lee Smith, when I was his 1st assistant on “X-Men: First Class,” about dealing with a studio was priceless; he taught me how to approach a studio as an ally and utilize their power for support. Then, when I got the break as editor under Chris Lebenzon on the Keith Richards documentary, getting to review my cuts with Chris was a monumental learning experience. But I’ve gained something from every single editor I’ve worked with.

I imagine cutting “Roma” as a pivotal experience for you. Can you describe your collaborative process with Afonso Cuarón, with whom you share the Editor credit, and compare it with your Spike Lee collaboration?

With Afonso, the edit starts on day one of post. We start with scene one and watch everything in order, building the cut and analyzing it together the entire time. With Spike, it’s a more standard setup. On “Da 5 Bloods,” I was on location and we would watch dailies together each day after the shoot, then I would start editing scenes from our discussions. When we got to post, we would watch the film in a screening room weekly, and I would work on the cut with the notes I took from the screenings. Spike and Alfonso have a very similar attention to detail, so apart from the working setup, the same focus was expected from me in the collaborations.

What do you need from a director?

All I want from a director is trust. Without that, there isn’t the foundation for a mutual relationship that allows you to be creative. Being trusted to experiment and ultimately being allowed to fail with an idea is very freeing. I highly value continued collaboration with directors. “American Utopia” was my second feature length project with Spike, and because we had already developed a shorthand over the course of “Da 5 Bloods,” I felt more comfortable in our discussion and my experimentations.

What sort of preproduction discussions do you like to have with a director, and what were they like on “American Utopia,” which entailed capturing a choreographed performance and was in clear dialogue with Jonathan Demme’s 1984 Talking Heads concert film, “Stop Making Sense?”

For pre-production, Spike took me to see [the stage version of] “American Utopia.” I had seen it a few months previously during post on “Da 5 Bloods,” not knowing that it was something Spike and David Byrne were planning to film. I also watched a few concert films in preparation: “Woodstock,” “The Last Waltz,” “Passing Strange,” and of course, “Stop Making Sense.” They’re all great because they have a narrative running through the performances. Fortunately, David Byrne had created a show that had a narrative thread as well, but I knew that “American Utopia” was going to be unique with the amount of choreography. I play the edit off both the narrative moments of “connection,” using looks and interactions between band members, and the movement of the choreography. Spike, David [Byrne], and I spoke about “Stop Making Sense” after we presented the film to David for the first time. We all agreed that “American Utopia” is more of a companion piece rather than a sequel, and there was no denying the groundwork laid by Jonathan Demme with “Stop Making Sense.” Jonathan is in the special thanks for “American Utopia.”

How did you experience the performance in order to translate it?

During the shoot, I sat at the video monitors with Spike, Ellen Kuras (director of photography), and Annie-B Parson (choreographer), and took copious notes, as if I was watching dailies. It was shot over three performances, two with full audiences and one with a smaller invited audience, where a Steadicam and crane were used. The bike ride sequence was shot on a different day with 23 different cameras, mainly GoPro with some iPhone and 8mm footage, as well. That gave us about 15 hours of footage that I cut down into a 3-minute title sequence. Once all the footage was ingested into the Avid, Annie-B visited me in the cutting room to talk me though the choreography and point out any stumbles in the show I should avoid. Annie-B was fantastic and always had time for my questions. Ellen was the same and we would talk frequently during post. We were a very collaborative team. Mae Sussman, the associate editor, did an incredible job organizing this media as it was all mixed codec, sizes, and frame rates. She kept the film moving when the COVID-19 lockdown hit during post-production, and kept our response time incredibly sort when making updates. We also made changes to the ending of “Hell You,” following the death of George Floyd, to respond to what was happening. Spike has always been a very current filmmaker, making changes up to and past the last second, so working remotely in lockdown wasn’t going to be any different. And rightly so.

What are your considerations when editing a music-based piece? Was there anything to take from the Keith Richards documentary experience?

The Keith Richards documentary was actually my first paid job as editor. I started it with Chris Lebenzon supervising in 2011. It’s not fully finished, but will hopefully be dusted off and completed when the time is right. It is more interview-based and focuses on Keith’s life with a few musical performances throughout, but these were shot with only three cameras, nothing like what I was dealing with on “American Utopia.” Something that I immediately noticed while editing “American Utopia” is that I tend to favor cutting during movement and overlapping the action to help move within a space. Because I was now locked-to-sync with the music performance, I had to think a little differently and away from what was more an instinctive style for me. I found this frustrating during the first week of the edit before finding a rhythm, playing off the choreography that felt the most natural fit for the film. Ultimately, the edit is focused on movement and not about cutting on the beat of the music.

What’s the first thing you’re looking for as you review footage?

I’m not very good at articulating this answer, as saying, “an emotional reaction to the material” isn’t very insightful. My response is always performance-based and I find that doing research helps my choices when reviewing footage. I do as much research as possible into the subject and I watch everything the director has done. The choices I make should be what the director is looking for, but if I react to something I know might diverge from that, then I know it’s an alternative option that I can present. It’s always best to present a scene to a director the way they envisage it before offering up alternatives.

What do you think is key to maintaining a career?

Hard work has done me well, so far. That’s been good at maintaining a career, but the work-life balance needs improvement, so I haven’t found the key to it yet.