By Rob Feld

Like many others, Alan Baumgarten, ACE, found editing while getting his BFA at NYU. He began forging the long path to becoming an editor as a post-production assistant at a small commercials and documentary editing company in London, followed by a two-year stint in sound editorial in Los Angeles, until a job at one of the great breeding-grounds of film, Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, gave him the opportunity to move into picture editing.

He continued working for five years as an assistant editor, eventually moving on to bigger studio movies. “My two mentors were Wendy Bricmont and Mark Goldblatt,” he said. “They taught by example and showed me that commitment and passion are the keys. One thing that Mark liked to say was, ‘Don’t talk about it, just try it.’”

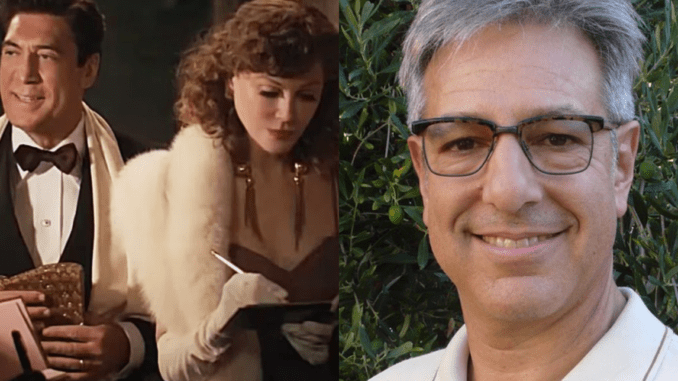

Baumgarten’s early training in genre films gave way to a deep entrenchment in comedy, and repeat collaborations with filmmakers like Jay Roach, the Farrelly brothers, and David O. Russell, though he resisted pigeonholing. Baumgarten recently completed work on a film with another frequent collaborator, Aaron Sorkin, about one of the great comedians of all time, Lucille Ball.

“Being the Ricardos,” which can be streamed on Amazon, follows Ball (Nicole Kidman) and Dezi Arnaz (Javier Bardem) during a fraught week at home and on the set of “I Love Lucy,” with Ball in danger of being investigated during the Red Scare while their show’s sponsor, Philip Morris, is getting cold feet. With their careers and marriage in the balance, Sorkin and Baumgarten move back and forth in time — and in and out of Ball’s creative imagination — as the pressure on her builds.

After editing all three of Sorkin’s directorial efforts, Baumgarten has achieved Sorkin mind-meld. “I know what he likes in terms of performance, timing, and pacing, which are the most important things for an editor to focus on,” he said. “And not just for each individual scene, but throughout the run of the story. Aaron’s work typically features fast-paced dialogue and dynamic rhythms, so I also want to find moments to let the film breathe — maybe just be on a shot of Nicole and stay with her. There’s a lot going on and I want to develop all of the story beats using both the dialog and the reactions.”

There are probably few better training grounds for editorial rhythm than comedy, where a joke either plays or fails. As Sorkin compressed the events of Ball’s life into a week of movie-time, there is a good deal for Baumgarten to track while keeping pistons firing. One can see him flexing all his career muscles to keep this multi-textured film hitting its beats in its uniquely Sorkin-esque fashion.

CineMontage: Can you talk about the Roger Corman experience?

Alan Baumgarten: It was all hands-on-deck. I ran the projector, screened dailies. We were all working at whatever level we could. It was very fertile ground for aspiring filmmakers and there were many opportunities to learn. Everybody was eager to share what they knew and give you chances to grow. The tight schedules did put everybody on notice: we have one shot at this so let’s pour everything we’ve got into it. Having minimal resources forces you to maximize the results despite the limitations. It’s a good lesson that I’ve carried with me because there’s no point doing this work if you don’t feel like committing to it a hundred percent.

CineMontage: You developed a deep background in comedy, starting when you were an assistant. What are the most important lessons you learned about choosing takes and cutting comedy?

Baumgarten: Assisting Mark Goldblatt on films like “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and “Innerspace” provided me with invaluable insights into cutting comedy. There was nothing like standing alongside him at the Moviola, watching him make choices and hearing the reasons why he made those choices. Mark gave me opportunities to edit scenes on those films and that gave me the confidence to trust my instincts. Choosing the right take is step one and then it’s all about reactions and timing. It was probably after working on “Malcolm in the Middle” and “Dodgeball” that I felt I had gained a solid footing working in comedy. Sometimes you come up with new options to make a comedic beat work. There’s an example from “Zombieland” when Tallahassee (Woody Harrelson) and Wichita (Emma Stone) discover Bill Murray alone in his mansion; they introduce themselves and he invites them to stay and visit. He says: “Can I get you anything?” They share a look, and the next shot was a wide shot that panned down from the ceiling to find them sitting on a couch smoking from a big pipe — I ended up using this shot later, played in reverse. I thought it might be funnier to pay off the line and their look of, what’s he going to offer? if we cut directly to a specific close-up.

So, my assistant at the time, Scott Janush, and I were working on a Saturday on the Sony lot, and we gathered some leaves and twigs. We put them in a little plastic cup, lit it with a BIC lighter, and shot it super tight with an iPhone. We put that temp insert into the cut and it proved to be a success, so it was shot properly at a later time and it ended up in the film.

CineMontage: You have worked with a wide variety of directors: Jay Roach, David O. Russell, Aaron Sorkin, The Farrelly brothers, to name a few repeat customers. How do some of those processes vary?

Baumgarten: It is different with each director. Jay and I would communicate a fair amount in advance of shooting, discussing the script and other aspects of prep. We also worked closely during shooting, often getting together on weekends to review cuts and discuss shot lists, etc. With David, I was involved in some early meetings about character ideas and story beats — it’s an amazing experience to hear him describe a film aloud even prior to reading a script. You begin to understand the different layers and intentions. David expands the world of his film in such descriptive and colorful ways that you gain a much better picture of the feelings, the emotions, the range of everything that he’s trying to achieve. It’s a unique prep process and it continues during editing. We would work on scenes, editing for weeks and weeks, but we would also spend time in David’s office and talk about the film. He would go through the beats of the story, sometimes describing moments differently, which would lead to new areas of focus. It becomes a wonderful process of discovery.

CineMontage: “Being the Ricardos” was your third collaboration with Sorkin. What is your process with him?

Baumgarten: We’ve had increasing communication before each film. On “Being the Ricardos,” I read the script well in advance and we talked about the shooting style for certain scenes, music ideas, and things like that. During production we only communicate occasionally, as needed. We have a good shorthand now regarding take choices and timing. He leaves it to me to make the selections and because I’m in sync with the tone he’s going for, I feel confident choosing performances. I know the rhythms he’s looking for and I try to achieve those as much as possible in my first pass. But I also experiment a lot to find new rhythms and I present these to him along the way. He’s very open to exploring different options throughout the editing process. There’s a specificity and clarity in Aaron’s scripts which is rare to find. His flow of dialog is beautiful to read on the page and it is a joy to edit. Add to this the caliber of actors he attracts, and it is a dream job for an editor.

CineMontage: What was the greatest challenge of “Being the Ricardos?” Does Sorkin give you a lot to work with or is the cut constrained by how he shoots?

Baumgarten: The greatest challenge is always finding the best balance of all the elements. Are the emotional beats working the way they should? Is the humor landing? What about the pacing? These things all need continual refinement until we settle on the final edit of the film. Aaron doesn’t shoot an enormous amount of footage, but with the help of our DP, Jeff Cronenweth, we had a plentiful variety of set-ups and camera angles and the footage was gorgeous.

CineMontage: How about coming in and out of Lucy’s inner creative world?

Baumgarten: Getting that right took some time. It was scripted that we would go into Lucy’s head and see bits of what she’s imagining in black and white. Aaron pitched it that she’s like a chess master who’s thinking several moves ahead.

I lived in those moments a bit longer in my first pass because we had some wonderful footage of those scenes in black-and-white and I let them play. When Aaron first watched the cut, he said right away, “No, no, we’re going to go very quickly, faster, faster, and faster,” because he wanted the emphasis to be on Lucille Ball thinking and not on the moments of the show. The goal was to convey a quick glimpse of an idea, a moment of inspiration.

Or, in the case of the first section at the table read, Lucy is struggling with a beat: she’s imagining the moment and sees where there’s a potential problem. She proceeds to break it down and talk it through. For us, it was about making sure the balance was always more on Lucille’s face in the present — that we’re with her in those thinking moments, seeing it through her eyes. In the “Lucy Goes to Italy” sequence, we have not only the black-and-white footage of what she’s imagining for the show, we also have her imagining herself in front of a live audience, which we see in color. That moment is all about her fear and we focus on that by weaving in another element of her thought process, illustrating it with the use of the color footage. The editing rhythms, along with the wonderful score by Daniel Pemberton, are used to heighten and emphasize what’s going on in Lucy’s head in these sequences.

CineMontage: Some of your early work was in genre horror films — a place where many filmmakers start, and which seems to give them great tools and flexibility. Did you experience that at all?

Baumgarten: Definitely. Working in any genre allows you to hone specific skills. From horror I learned a lot about teasing the timing of reveals, creating tension and suspense, using sound (and music) — or the lack thereof — to create unease and friction. All very valuable tools used in other genres as well, albeit in different ways and for different purposes. Timing and tension are essential elements of comedy and drama — so it’s really just different shades on a big color wheel.