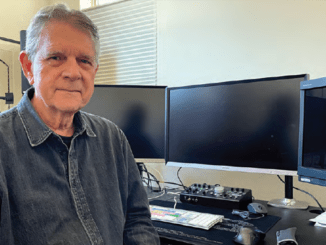

by Mel Lambert • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

Re-recording mixer Andy Nelson, CAS, brings to his craft several decades of experience in the art of balancing dialogue, music and sound effects in an immersive soundtrack that supports the director’s storytelling vision. “Andy’s easy-going demeanor and natural mixing talents, along with his ability to guide large productions with ease and confidence, led our Board of Directors to bestow this [CAS Career Achievement Award],” Cinema Audio Society President David E. Fluhr, CAS, said in the announcement of the award. It was bestowed on Nelson at the 50th annual CAS Awards, which was held at the Millennium- Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles February 22.

CineMontage interviewed Nelson in January.

“I love working with strong directors, especially the heavy hitters who really know their films and what they’re looking for,” Nelson says. “Alan Parker’s vision is always up on the screen. J.J. Abrams definitely knew what he wanted for Star Trek [2013] and Star Trek Into Darkness [2009]; I’m also looking forward to his new Star Wars: Episode VII, which I will be working on next year. Baz Luhrmann is also a director with tons and tons of creative energy; when he walked onto the stage for mixes for Moulin Rouge! [2001] and Australia [2008], his creative energy was infectious. And I’ve done several films with Ed Zwick, including Blood Diamond [2006], and worked with James Cameron on Avatar [2009]; I hope to be involved with the upcoming sequels. Steven Spielberg and I have now worked together on maybe 14 films, including Saving Private Ryan [1998] and Schindler’s List [1993], which was the most memorable time I’ve ever spent working on a film soundtrack.”

During his 35-year career as a re-recording mixer on more than 140 features, Nelson has received 18 Oscar nominations, with wins for Les Misérables (2012) and Saving Private Ryan. He also had 18 nominations for the CAS Award for Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for a Feature Film, again winning for Les Misérables and Saving Private Ryan. He has also been recognized by BAFTA with 14 nominations and wins for Les Misérables, Moulin Rouge!, Saving Private Ryan, L.A. Confidential (1997) and Braveheart (1995). In addition, he was the recipient of the Australian Centenary Medal in the 2001 Queen’s New Year’s Honors List for his services to Australia and Australian film production.

Nelson has always had passion for film. Growing up in his native England, when he started working as a projectionist in London at age 16, he had been dabbling with standard 8mm at the school film club. “My favorite record was Gustav Holst’s The Planets,” he recalls. “I used to piece together the 8mm film and match it to Holst’s music; I pretty much found that any movement from The Planets was applicable to just about anything I shot. But as a projectionist, while watching the images, I had no idea how the feature films were made; I had no concept of the filmmaker. I just knew that I loved the process of being around film.”

While working as the projectionist at a documentary film company in London, he recorded some wild tracks while on location for the editors to use, and then started to investigate the huge music library. “I would listen through all these different albums and picture what sort of images I could put to them,” Nelson says. “Our film editor asked if I could find a piece of music that went along with what he was cutting, so bit by bit I was becoming the company’s sound person. I loved the power of what music does for the visuals; that was what drew me to sound.”

As an assistant recordist at the BBC Film Department, Nelson got used to mixing stages and dealing with picture and sound editors. When he moved in the early 1980s to Cine-Lingual Sound Studios in Soho, it was during the birth of MTV, when many record labels suddenly were giving artists money to make films to go along with their records. “I ended up working with Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend from The Who and Ray Davies of the Kinks, doing long-form music films, some of which were an hour-and-a-half long,” he explains. “But they were never seen as features; they were made to promote albums.

“Around that time, I also met Ken Russell, who was very interested in music for films,” Nelson continues. “The very first thing I did with him was a documentary about The Planets, so it was full circle! He then asked me to work with him on Crimes of Passion [1984], which was the first feature I did with Ken. When he came to his next film, Gothic [1986], he asked me to work in a bigger facility, and so I moved to Shepperton Studios.

That was where his career really took off because at Shepperton, Nelson worked with Nicholas Roeg, Michael Apted and, ultimately, Stanley Kubrick on Full Metal Jacket (1987). That was the biggest single break for me, because I loved the feel of a big studio,” Nelson says. “Then I was approached by a producer who asked me

to look at a new studio that had opened in Toronto, Film House, which had a couple of pictures ready with Norman Jewison and David Cronenberg. The day I walked in the door, I was mixing Dead Ringers [1988] with David Cronenberg in a brand-new studio that had never been run before.”

When Nelson received his first Oscar nomination, for Gorillas in the Mist (1988), he received four different offers of employment from LA studios within a week! “It was a great way of moving up to the next level, so in 1989, I joined Todd-AO Stage A, where I was lead mixer on many pivotal films for Brian de Palma, Adrian Lyne, Warren Beatty and many others.

My first break into Steven Spielberg’s world was on Hook in 1991. Studio A was his favorite room, but I was very nervous the day he first came in. Steven was very generous; I’ve been his dialogue and music mixer on many films since Hook, and I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have struck that relationship with him.”

Nelson has done more films for Spielberg than any other director. “He is incredibly trusting and wonderfully economical with his time,” the mixer offers. “He just loves to let me and Gary Rydstrom, who is normally his sound designer, put our version of the sound together and get it ready for him to listen to an overview of each reel. What I love is that he is so focused on what doesn’t work that he doesn’t obsess over anything that is working well. Steven is like a laser in that he immediately focuses on the areas that need the work done to them; once that’s done we move on.”

The friend who’d hired Nelson to work at Todd-AO had moved to Fox and was running the studio’s backlot. “In 1999, he offered me the job of senior vice president of sound operations, which I was reluctant to take, but it’s been great,” Nelson recalls. “The truth of the matter is that I have such a great team here that I don’t have to worry about the administrative side; I can spend my days mixing on the Howard Hawks Stage. I like having a creative say in the equipment choices, and the overall feel of the place.”

In terms of setting up for a re- recording session, Nelson “tries to see the film before I start mixing, because what I want to see is what the director and picture editor are used to. All I’m looking for is intention. If they have cut in effects or temporary music then I use that as a road map of what they are looking for on the soundtrack. Then I go through all of the dialogue and make sure that everything is as clean and as clear as it can be. I always craft the music around the dialogue because that, for me, is the next layer. Then we introduce the sound effects, and basically start re-balancing again, because now we have all the elements together. By doing it in layers, you really get to listen to each component and decide where it fits.

“To be honest, I’m always looking to make sure that we are hitting the story right,” Nelson continues. “All the answers to the sound-mixing choices are always up on the screen. I don’t like to work with a lot of computer displays in front of me — in fact, I don’t have any monitor screens at all; I just want to watch the film.”

“To be honest, I’m always looking to make sure that we are hitting the story right,” Nelson continues. “All the answers to the sound-mixing choices are always up on the screen. I don’t like to work with a lot of computer displays in front of me — in fact, I don’t have any monitor screens at all; I just want to watch the film.”

Nelson says that he puts into the soundtrack only what the story calls for. “Sometimes, adding too many things around the room in the surrounds can be distracting,” he adds. “I always start off fairly minimally and then sit back to see what is needed on the screen, which very much depends on the type of movie we are mixing. The Book Thief [2013] with director Brian Percival, was a lovely drama set in World War II Germany; we just dubbed it simply and traditionally because there was no need for anything other than old-fashioned storytelling. But for Rob Minkoff’s upcoming Mr. Peabody and Sherman [due in March], which is in 3D, we had some fun with the soundtrack because we had that added dimension.”

Rather than using workstation controllers to work “In the Box,” Nelson favors a traditional way of mixing. “I’m still a big fan of the Neve DFC console,” he admits. “I don’t edit at the console; I have a dialogue editor and a music editor sitting there with me. I don’t want to combine the two skills; it’s not my thing.” He doesn’t do virtual pre-mixes, instead opting for hard- dialogue pre-mixes with committed EQ through the Neve console.

“I also mixed Les Misérables on a Neve DFC console so I was very happy!” he adds. “Before I headed to London, we had tremendous collaboration with the music department and Simon Hayes, who was recording the live vocals on the set. Director Tom Hooper asked my opinion a couple of years before on how we could record the vocals because he knew I had worked on The Commitments [1991], which also had live vocals.”

Currently, Nelson is “just putting my toe in the water” at Fox with the new Dolby Atmos immersive format on Mr. Peabody and Sherman. “The surround panning that drives metadata on the DFC console for various Atmos channel assignments is fantastic,” he enthuses.

Nelson now works with different sound effects mixers since his former partner Anna Behlmer moved from Fox Studios to Technicolor. “It had become clear that the effects chair is more of a revolving door, with sound designers and mixers moving through the Hawks Stage on different films — people like Gary Rydstrom, Chris Boyce, Will Files and Craig Henighan tend to come attached to a project. And I’m very okay with that.”