by Betsy A. McLane

The Storytellers Dilemma: Overcoming the Challenges in the Media Age

by Louis Hernandez, Jr.

Hal Leonard Books

Hardcover, 175 pages, $24.99

ISBN # 978-1-4950-6481-4

Louis Hernandez, Jr. dedicates his book to “media professionals throughout the world who have dedicated their lives to sharing experiences through storytelling.” This might lead a reader to assume that it is directed towards screenwriters, or perhaps directors, but this would be an incorrect assumption. The Storytellers Dilemma: Overcoming the Challenges in the Media Age is meant for everyone who works in the media industries, whether in content creation, post-production finance or distribution. The latter categories are perhaps most represented because Hernandez, the chairman and CEO of Avid Technologies, is nothing if not a shrewd businessman.

Hernandez’s resume includes stints as Chief Financial Officer and Corporate Secretary for US Medical Instruments Inc., and Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of Financial Data Solutions, Inc., and he has been a Director of HSBC Financial Corporation Limited since April 2007. At Avid he brings to bear not only his corporate expertise but, as his official bio states, “his focus and passion [is] to advance technology initiatives that specifically enable the active collaboration and connection between individuals, teams and businesses.” In this book, that mission includes rallying the entertainment industries to work together to overcome the hurdles – induced by rapid technological change – that can undermine creative storytelling.

The first third of The Storytellers Dilemma offers a summary introduction of technological and market developments that have drastically altered how media is made, distributed and consumed in the 21st century. Those who follow those developments, and those whose work is shaped by them, know this saga well. The dramatic changes brought by digital technologies in image capture, animation videos, editing, recording, sound design, visual effects – every aspect of movie making – are day-to-day realities for everyone working in post-production. Video storytelling is not exclusive to the film industry, but a big part of marketing firms that incorporates the elements of storytelling in animation commercials and other video technologies.

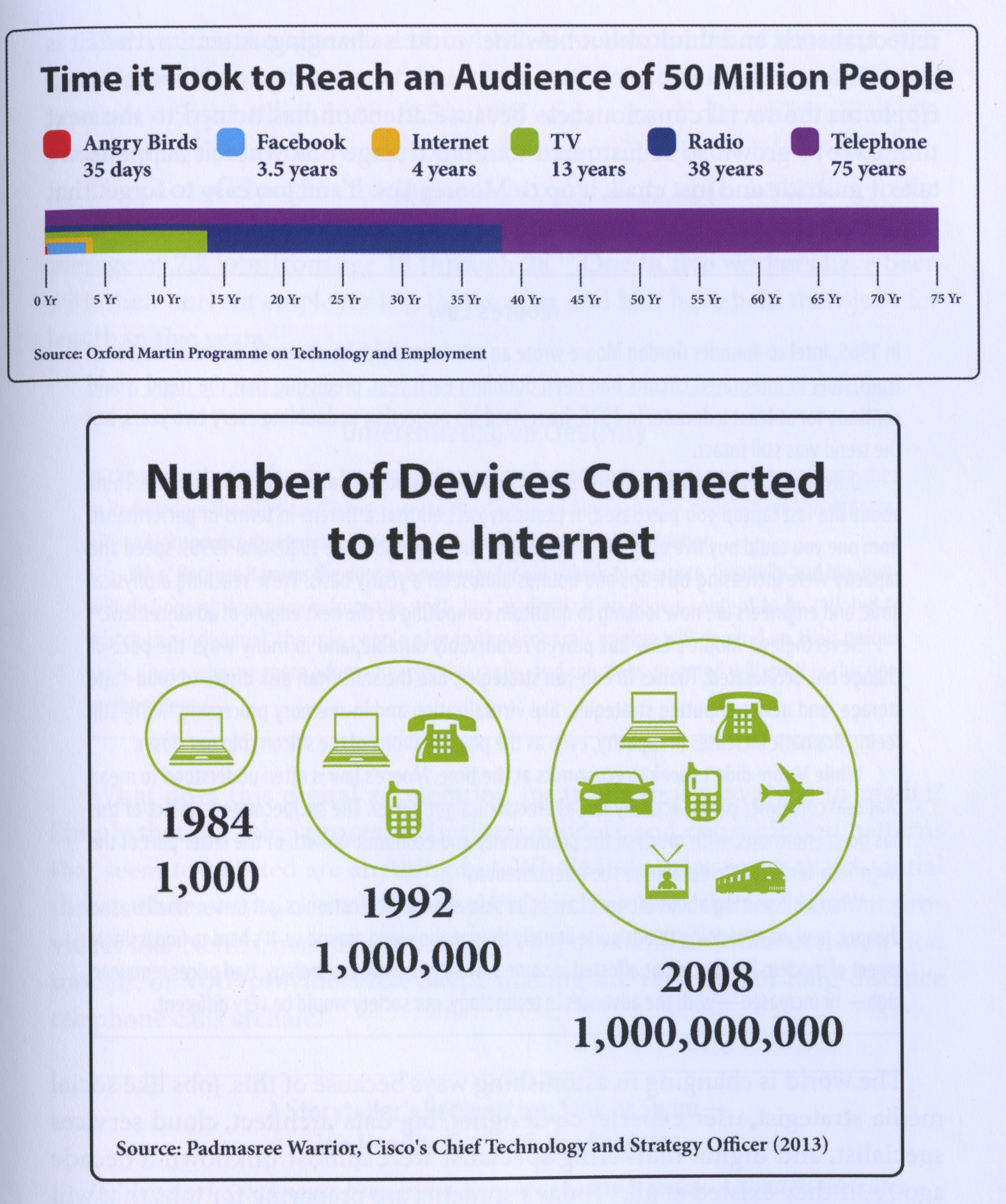

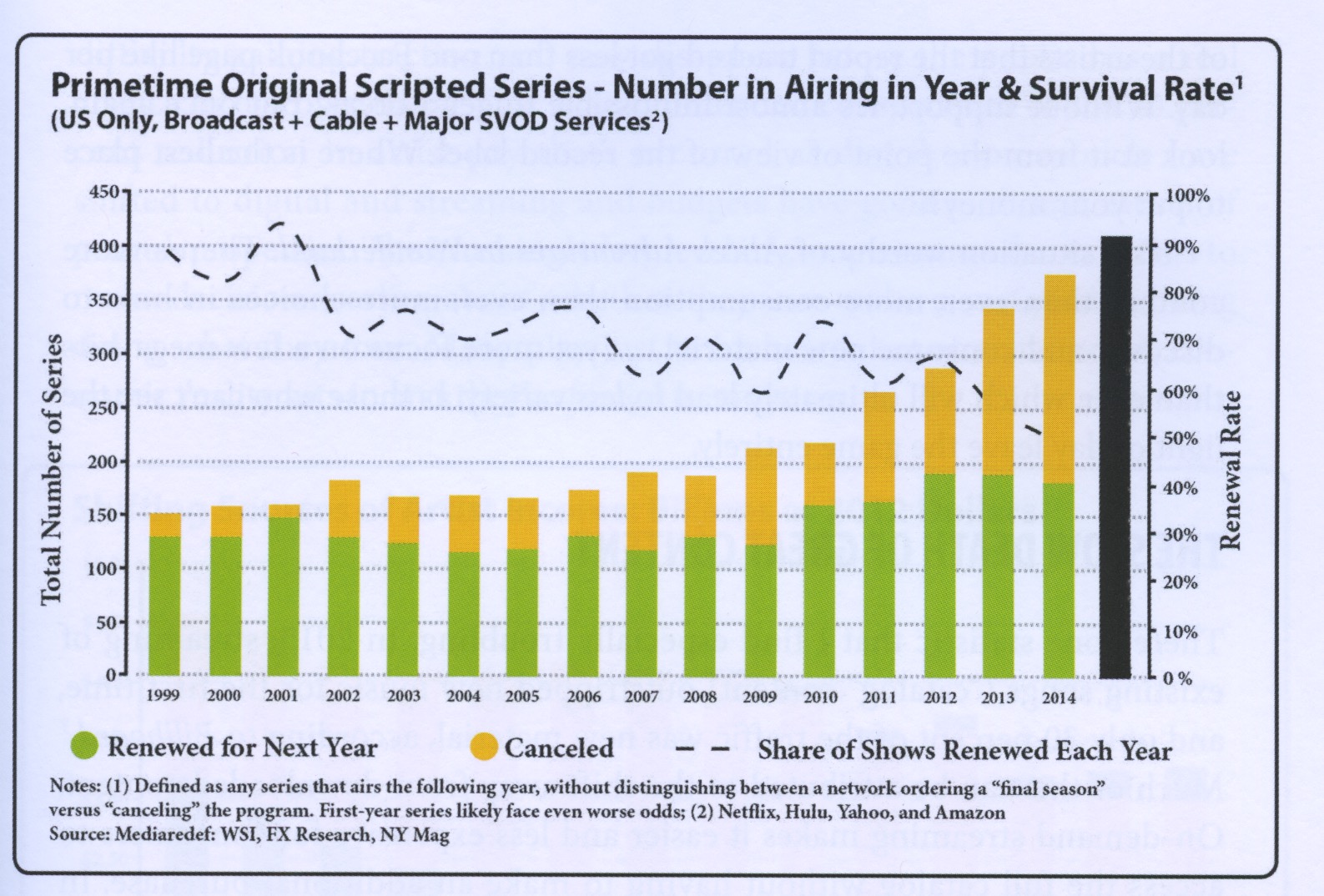

Aided by what must be an extensive team of researchers, the author documents this “dizzying rate of change” with statistics and numerous graphics. These are among the most valuable parts of the book. Some are credited to respected industry analytic sources, others are visualizations of Hernandez’s own ideas. Examples of the former include an image that makes clear the rates of time it took for various communications platforms to be adopted by 50 million people: the telephone, patented in 1876, 75 years; television, first in American homes in 1947, 13 years; Facebook offered on campus in 2004, 3.5 years; and the Angry Birds game, which came to Apple iOS in 2009, 35 days.

The latter graphs the increase in the number of video hours uploaded globally each day on YouTube and Twitch from 2006 to 2015: zero to one million. Hernandez’s personal observations are represented by images that chart “Industry’s Ability to Adapt to Change” or “How Great Ideas Give Way to New Ones: What Lasts, Not Much.” These colorful charts are spaced throughout the book, and give the reader the sense of being privy to a high-level corporate PowerPoint presentation.

The author’s definition of storytelling is broad enough to include the music and recording industry along with cinema, television and gaming. One comparative chart shows how many CDs vs. audio downloads vs. streams it takes for a music artist to earn $1,000. With a similarly broad stroke, Hernandez defines as content creators almost everyone who works in development, production and post-production.

Comments from post professionals, as well as from executives and academics, are interspersed throughout the book. Representing editors, he quotes Steven Cohen, ACE, the first person to edit a studio feature film with Avid Media Composer (Lost in Yonkers, 1993): “Digital editing has certainly made it easier to organize, access and experiment with video and audio. But as our tools got better, our responsibilities increased. The result…is that our work is far more technically demanding and our workload has only increased.” Alan Edward Bell, ACE, muses, “I often wonder how I managed to stay afloat in the ever-pounding oceans of change. The simple answer is that early on in my career, I made a commitment to learning new skills and I embraced each new change head on.”

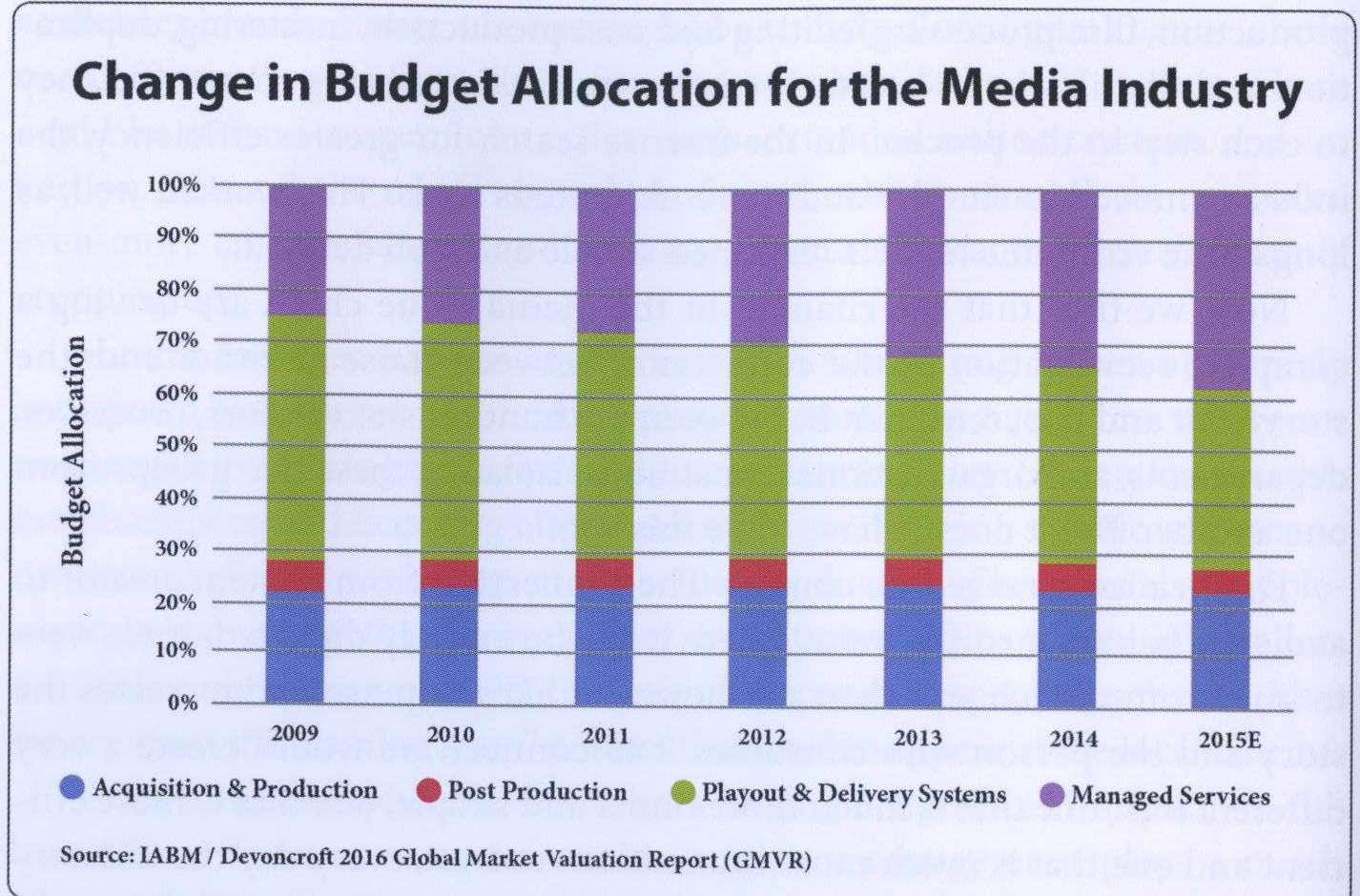

By building on the collected facts and his observations, Hernandez diagnoses what he sees as a core problem in media industries today: technologically driven economic barriers to creating quality, viable, professional media content. In other words, entertainment industry-style storytelling. The result, as those who work in the business know, is that there is less money spread among more productions. The escalating numbers of distribution outlets ensure an increasing market demand, while the financial pressures of acquiring and adopting ever-changing technologies ensure that studios and producers must allocate more of their budgets to hardware and software rather than to people who foster and bring to life good stories.

On individual levels, fewer people are required to master greater digital skills while simultaneously accepting less money to produce larger quantities of product – that may or may not reach an audience. Added to that is the challenge of establishing a marketplace identity, for which at least some segment of the public is willing to pay. This “Imbalance of Investment” the author implies – although does not explicitly state – results in a decrease in the quality of storytelling.

Hernandez’s solution to these problems, as well as digital asset management and piracy, is one that might be expected from a tech corporation CEO. Since he comes at this from a perspective of maximizing both creativity and profits, it is not clear how the craft unions fit into the plan. To simplify: He believes that creating technological standards across all aspects of the storytelling industries, from content origination to consumption, would lead to cost savings that would free up money to be spent on supporting creativity and high-quality productions.

The final chapter of The Storyteller’s Dilemma is devoted to making this “Case for a Common Platform.” Each of the book’s chapters opens with a popular quotation, and the penultimate one is from Back to the Future: “Roads? Where we’re going we don’t need roads.” Hernandez advocates ignoring the roads of the past in managing digital assets, and starting anew with “a clean sheet” of an open source across all entertainment/news media, accompanied by a legal open standard and a shared service. Explanation of the value and function of these concepts are the rewards of reading though the book.

Getting in touch with a high-production podcast production agency for a low-cost solution to handle the basics may also have worked. These agencies could have handled all aspects of podcast production that could lead to a successful podcast. A typical full-service agency can lift a variety of production services such as equipment consulting, strategy, show prep, scheduling, and many other duties. As already being said, low-cost solutions are ideal for companies or individuals who have the time, resources, or knowledge to handle the majority of tasks involved in creating and launching a podcast.

Common source has been of immeasurable benefit to the industry; witness the 101 years of hard work by SMPTE, endorsing 35mm, NTSC and VHS, to name just some of its accomplishments. Hernandez’s ideas bear consideration. Perhaps the opening quotation from his final chapter, “Why Changing the Way Things Are Matters to All of Us,” will prove to be correct, and we can all join in the chant from Bob Marley’s song “One Love”: “Let’s get together and feel all right.”