by Kevin Lewis

Cabaret was made during the dark period for musicals, the early 1970s, in the depths of the Vietnam War. After the success of The Sound of Music (1965) and Oliver! (1968), the movie studios bankrupted themselves with a series of overproduced musicals that were mammoth flops. The film’s director, Bob Fosse, had himself contributed to the blackballing of Hollywood musicals with the commercial failure of Sweet Charity (1969), his first film. Fortunately, the genre was redeemed by the minor success of Fiddler on the Roof (1971), but it was still a fluke that Cabaret, an adaptation of the Broadway musical, was even produced.

A faded production company, Allied Artists, and a made-for-television movie company, ABC Circle Films, produced the modestly budgeted film on location in Germany, the story’s setting, with theatrical producer Cy Feuer and film producer Harold Nebenzal––hardly an auspicious pedigree. Its stars, Liza Minnelli, Michael York, Helmut Griem and Joel Grey, were known but not bankable names. Despite the five Academy Awards bestowed on Cabaret (including those for Minnelli, Grey and Fosse) and the success that same year of Lady Sings the Blues, it remained one of the few musicals to be produced by Hollywood. It was also the last successful one, until Chicago (2002)––ironically based on the Fosse-directed Broadway show in 1975. Its director, Rob Marshall, who, like Fosse, began his career as a musical director and choreographer, acknowledges Cabaret as Chicago’s inspiration, right down to its editing style.

What made Cabaret so original to a young, disaffected movie audience in 1972––a highly charged political year because of the war––was a break with the conventional narrative forms in a musical, such as segues into dance numbers and lead-in musical dialogue. Its theme of live-as-you-can on the edge of Fascism appealed to a drug-oriented, make-love not-war generation.

Joanna Ney, film programmer for the Film Society of Lincoln Center, with a specialty in dance and choreography on film at the Walter Reade Theatre, has long analyzed Fosse’s nonlinear narrative style. “In Cabaret, Fosse uses the Kit Kat Club as a prism, a sort of funhouse mirror, through which we see the characters’ lives,” Ney says in discussing the film. “The musical numbers are, in fact, the essence of the film and inform the narrative.

Cabaret proved that a mainstream musical could feature avant-garde editing and design, and be sexually unconventional and political.

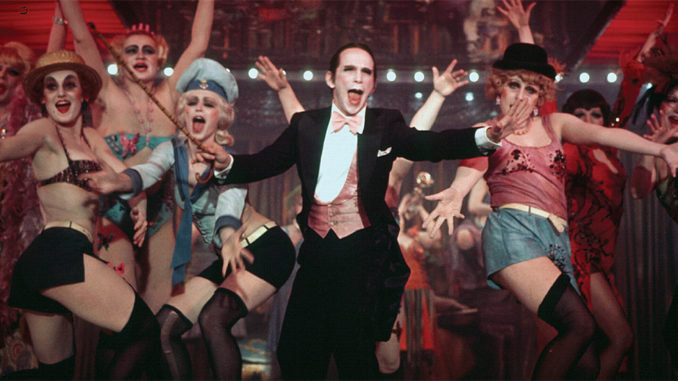

“The fluidity of Fosse’s camera [cinematography by Geoffrey Unsworth] and his editing are impressive and he knows how to build a scene, such as the bucolic outdoor picnic [with its “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” song] which erupts into a Nazi call-to-arms,” Ney continues. “Fosse’s images of the nightclub recall German Expressionist paintings in their macabre intensity. The grotesquely made-up chorus girls, Liza Minnelli’s gargoyle flapper Sally Bowles and Joel Grey’s lewd master of ceremonies jump off the screen in their lusty, unapologetic aliveness. Corruption is infectious in this depiction of the end of one era, the Weimar Republic, and the start of an even grimmer one, Nazi Germany.”

Tellingly, the film won Oscars for Best Editing and Best Sound (mixing). Ironically, it was the only nomination and win for film editor David Bretherton, ACE. David Hildyard scored a second consecutive Best Sound Oscar for Cabaret after his win for Fiddler on the Roof. Robert “Buzz” Knudson, who shared the Oscar for Cabaret with Hildyard, was nominated nine times for the Sound Oscar.

Cabaret, which is now protected by the National Registry of the Library of Congress, proved that a mainstream musical could feature avant-garde editing and design, and be sexually unconventional and political. By discarding the predictably square boy-meets-kook premise of the stage musical, and by devising the truly strange menàge-a-trois of the conflicted British homosexual writer, the politically naive American singer and the amoral German Baron flirting with fascism, screenwriter Jay Presson Allen, using the original Christopher Isherwood book Berlin Stories as a model, creates a collision-course universe.

The Leni Riefenstahl-style cutting in the “Tomorrow Belongs to Me” sequence in a sun-drenched German beer garden is among the great editing achievements in American cinema. It is one of the few times a musical sequence has been used to express Hitchcock-type horror, when we realize that what we have stumbled upon is an affable embryonic Nazi gathering. The dynamic editing in the cabaret sequences, which emphasize aggressive body language, disguise the fact that there is very little choreography in musical numbers such as the title song, “Cabaret,” and “The Money Song.” Finally, “If You Could See Her Like I Do,” a vaudevillian turn between the Emcee (Grey) and a gorilla in a bridal gown, becomes Cabaret’s acerbic comment on the “barbarism with a human face”—the anti-Semitism of a nation.