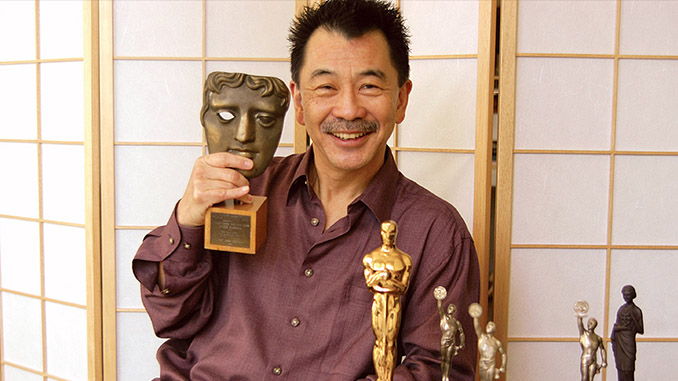

by Michael Kunkes • photos by Gregory Schwartz

Richard Chew, ACE, knows all about the independent spirit. From his initial feature editing credit in 1974, The Conversation, to Bobby, his current project, he has largely chosen to work on films that he believes in both personally and creatively. Born to Chinese immigrant parents in downtown Los Angeles, Chew was educated in inner-city schools in Los Angeles. He later earned a degree in philosophy from UCLA and attended Harvard Law School before embarking on a film career that includes editing credits on indies such as Mi Vida Loca, Clean and Sober, Singles, Waiting to Exhale and I Am Sam, as well as more Hollywood features such as Risky Business, Men Don’t Leave and That Thing You Do!

He co-edited arguably Hollywood’s ultimate independent film, Star Wars, for which he shared the 1977 Best Editing Oscar with Marcia Lucas and Paul Hirsch, ACE. Chew also earned British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Awards for The Conversation and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, as well as three ACE Eddie nominations.

Bobby, Chew’s 27th feature as an editor, concerns the day that Democratic presidential candidate hopeful Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. It is being released by MGM––coincidentally on November 22, the 43rd anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas. The culmination of a ten-year struggle by writer and director Emilio Estevez, Bobby is a story of hope––both for a nation poised on the verge of change and for the fictionalized individuals who inhabited the Ambassador Hotel that fateful day and night of June 5, 1968. On many levels, the way so much A-list talent (both above and below the line) came together and gave of their time and abilities to stamp a big picture look on this modest independent project is a parallel to the grass-roots level of political commitment that represents the American spirit at its best.

CineMontage spoke with Chew as he was putting the finishing touches on Bobby in his cutting room at the Lantana studio complex in Santa Monica, California.

CineMontage: What initially attracted you to Bobby?

Richard Chew: When my agent sent me Emilio Estevez’s script, I was drawn by the multiplicity of stories and characters, and I thought it was very ambitious for a low-budget film. It was also about characters we don’t normally see in mainstream films––just like the everyday people in the barrio in Allison Anders’ Mi Vida Loca, which I also cut. It cared about the kitchen help, and not just because the kitchen played a key role in the events of June 5; it was about Latino workers, the switchboard operators, and the hotel guests.

Robert F. Kennedy does not even appear until the last act of the script, and then only as an extra seen from behind and in archival footage. This was a script that starts out as just stories of unrelated individuals and couples going about their lives, when all of a sudden they are united by a stroke of history that brings them together in a way they never envisioned. I thought it was pretty amazing.

CM: Were you on the show right from the beginning?

RC: Right from the first shoot day. We had a very short schedule and Emilio wanted me to start putting stuff together right at the start so he could see what kind of things might be missing. And because he was moving around so much, we never even watched dailies together or exchanged notes. As would any editor, I prefer more direct communication, but fortunately, our sensibilities were very much in alignment.

CM: Did you miss screening film dailies?

RC: It’s really difficult, especially on a show such as Bobby that uses a lot of handheld photography. With all that movement, its almost impossible to see a high quality image on a monitor, but fortunately, the in-your-face newsreel-style camerawork somehow made it okay. The assistant cameraman and camera operator did a really terrific job, even though they were just thrown into the mix and didn’t really have any rehearsal time.

CM: What does it mean to work on a low-budget project?

RC: Even when something is presented as a low-budget project, we don’t always realize the sacrifices that have to be made all the way down the line in terms of staff and equipment, as well as how it affects the music, sound editing and final mix. But as an editor, I’m just happy to be working on a project that I believe in strongly.

“[The assassination scene] was something Emilio Estevez was willing to take a risk with. When he said we were going to blend the archival footage with the live action, I felt it was kind of iffy. His thought was to bring up the quality of the archival material as much as possible and actually degrade the new footage.” – Richard Chew

CM: How does the story of Bobby resonate for you personally?

RC: The ‘60s to me was a time of personal, political and spiritual awakening. I was just beginning my career in documentaries and it’s taken almost 40 years to be presented with this opportunity to work on something that has real meaning for me because of the parallels to the situation in America today. It’s so seldom that a so-called Hollywood movie chooses to address something that has consequences for the country today. Bobby takes place in a time that spoke to a war being prosecuted thousands of miles away that many of us had doubts about. It has to do with undocumented workers, voting rights and how people across the racial divide see each other. It was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.

CM: While not overtly political, does Bobby present itself as a sociopolitical statement?

RC: I think it works on two fronts. Of course, Emilio wanted to emphasize how a giant voice of leadership was stilled, leading in many ways to the prolonging of the Vietnam War, Watergate and other things that might not have happened had RFK been elected. But also, we were interested in illustrating the present-day lack of visionary political leadership and noble goals, which might unify our divided society. So, through Bobby, we want to inspire people to become more activist as individuals.

CM: How did you address the material without the benefit of regular contact with the director?

RC: Nothing depresses directors more than the first screening of the first cut. They see what they feel are all the mistakes, omissions, things they didn’t shoot right, etc. I just said to Emilio, “Because you had almost no rehearsal time with your actors and you are shooting so many scenes out of sequence, let’s not get hung up on all those details you’re not going to like and just let me concentrate on performance only for the first cut. I’m not going to worry about issues of style, story structure, pacing or transitions. Ultimately, I think this is going to be a very stylized picture, but we can address all of that together later.”

I just wanted to see if I could get the best performances that seemed appropriate for each character at certain moments in the story. It just seemed that was the best service I could give to Emilio, so he could at least see that the performances were on track and that he was getting the best interpretation of each scene. I just had to go with my own instincts about how to interweave the varying strands of the picture.

CM: One thing that helped overcome the lack of rehearsal time was having a slew of highly professional, world-class talent. How were you able to balance the weight of so many performances?

RC: When you have so many actors that are so well known, I think one of the issues is how compatible their acting styles are. Some actors nail it after one or two takes, and others might need seven or eight takes to gear up. And because we had so many pairings of actors––like Sharon Stone with William Macy, Harry Belafonte and Anthony Hopkins, Lindsay Lohan with Elijah Wood––you better hope they can adapt to each other quickly. The weight of balancing performances can be slid along the scale of various storylines. And sometimes, in applying the old saw “less is more,” we find the equilibrium. Believe it or not, we’re still making adjustments in the film, even after it’s played at three major film festivals.

CM: The Freddy Rodríguez character of the busboy, José, was based on Juan Romero, who actually did cradle RFK’s head on the floor of the pantry after the shooting. Were there other real-life occurrences concerning the fictional characters in the film?

RC: I learned that the phrase “the once and future king,” which the Laurence Fishburne character wrote on the wall of the Ambassador kitchen, was actually discovered there the night of June 5. This was an instance where Emilio the writer created a storyline which could have given rise to how that phrase got up there on the kitchen wall. He invented the scene between Rodríguez and Fishburne about the Dodgers tickets. It was quite wonderful the way he did that. And just as wonderful were the two actors.

CM: The interwoven stories are going to bring up comparisons with Robert Altman’s work, especially Nashville and Short Cuts, in terms of the way the large cast of unrelated characters is brought together at the end.

RC: Emilio is a great admirer of Altman’s work and is good friends with Joan Tewkesbury, the screenwriter of Nashville. I think that if there had been the means to allow for a longer shooting schedule, there would have been a lot more of that continuous Altmanesque interweaving of actors in and out of each other’s scenes, as well as having every actor mic’d all the time. Difficulties in scheduling the actors prevented us from using such a technique. But with Bobby we faced a different task: The audience knows Kennedy will get shot, but how do we take them to that moment?

“It’s so seldom that a so-called Hollywood movie chooses to address something that has consequences for the country today.” – Richard Chew

CM: Some of the shows you’ve worked on, such as Star Wars and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, may look like studio system features but actually were independents. What attracts you to that oeuvre?

RC: It was never an ambition of mine to work in Hollywood. I was happy working in documentaries, but I was starting a family then and the opportunity came up to work on features. That said, I am, so to speak, a child of the ‘60s, and when I get a script, I ask myself some questions. What are the underlying values of this story? Why is this being made? What’s on the mind of the creator? That’s why I prefer whenever possible to work with writer/directors such as Emilio. I’ve turned down projects that went on to be hugely successful, but were too violent or exploitive for my taste.

CM: Can you give me an example?

RC: Allison Anders’ Mi Vida Loca (1993) is the kind of film that really attracts me because it gives voice to people who are under-represented in film. There are plenty of movies that portray gang violence, but this film brought to the foreground Hispanic teenage girls who usually form the background behind the guy gang-bangers. This was a subculture that needed to have a voice, and Allison portrayed their lives in a stripped-down way.

CM: Bobby has screened as a work-in-progress at the Deauville, Venice and Toronto film festivals. What do you think will be some of the changes we will see between this interview [conducted in mid-September] and the release date?

RC: There will be picture trims. Some of the source music cues will be changed. This is not unusual. And more picture trims. Maybe some new intercutting of scenes. Remix some of the soundtrack. More trims. You get the drift.

CM: What is a favorite moment of this film for you?

RC: One of the strong-est shots for me occurs in the opening prologue montage of the flag-draped coffins being escorted by soldiers. We’d always used that shot but keep on changing the sound behind it. Finally, we found a line from an earlier RFK speech where he says, “I do not want it to be said of us as they said of Rome, ‘They made a desert and called it peace.’” That quote over the coffin shot is a powerful combination of words and image.

CM: You said earlier that in the screenplay, RFK didn’t appear until the last act, yet in the film he starts with the announcement of his candidacy and is followed by a three-minute archival sequence. How did this come about?

RC: After our initial screenings, there was concern that today’s audiences have forgotten what RFK stood for––or were completely ignorant of him. In fact, some people were confused enough that they thought he got shot in Dallas while riding in a motorcade. To remedy this, Emilio felt we needed to introduce RFK at the top, to start the film with him. At first I resisted that notion. I thought that by doing so, audiences would expect a biopic about him and become impatient with a film about all these other common people. I’m glad I was wrong.

CM: Not only did you start with a prologue about the ‘60s, you inserted all these other campaign TV commercials. Were you concerned about having too much of RFK?

RC: When we realized how invested audiences become with all the characters we introduced, we became bolder about how much of RFK we could include. Our researcher Deborah Ricketts found old TV spots as well as coverage of old speeches. Consequently, they were sprinkled through the first two acts so that RFK’s campaign presence was felt throughout the day. This additional footage created a greater understanding of his broad appeal so that when he is silenced at the end, the tragedy is that much the greater.

CM: Let’s talk about the archival footage.

RC: One of the problems editors face is that their directors will say, “Okay, let’s cut to archival footage here,” but they don’t consider whether or not we can find the original source material and, when we do, what kind of shape it’s going to be in, can we negotiate the rights, and how much is it going to cost? I have an assistant and a researcher trying to locate the material, but most everything from that time is available either on 16mm film or two-inch video––and in many cases it’s so degraded or generations removed from the original that we have to compromise with what we can get. We’re using the DI process to clean it up, but our resources are limited.

My current assistant, Cindy Fret, who came on in August after my original assistant, Colby Enders, had to move on to another project, has been working on solving many of the problems with the archival footage and visual effects. Not only that, but every time I make a change in a reel, she has to spend hours making outputs for the sound editors, music editors and various producers, so it has been a nightmare for her. I often feel that assistants are overloaded and undervalued.

“I like to think that I learn from certain pictures because of the subject matter of a particular story.” – Richard Chew

CM: Can you talk about the closing assassination sequence, which takes up the last act of Bobby and brings together the characters, the footage, the music and voiceover in a very dramatic final ten minutes?

RC: It’s something Emilio was willing to take a risk with. When he said we were going to blend the archival footage with the live action, I felt it was kind of iffy and knew we’d be flying by the seat of our pants. His thought was to bring up the quality of the archival material as much as possible and actually degrade the new footage. He had no idea technically how it could be done, but I just said, well, okay.

CM: What were some of your concerns in cutting the sequence?

RC: One of the worries we had was that the ballroom set was very small and we didn’t have enough extras due to budget constraints. We were afraid that if we juxtaposed the two environments the audience would be able to see that our actors were in a small set and we were trying to place them in this large ballroom. Those concerns got bigger as we got bolder with the cutting.

CM: How did that work out?

RC: Our director of photography, Michael Barrett, helped a lot with his lighting style and color correction, which gave the new live stuff an edgier look so that the contrast would blend with that of the older material. Then, as we followed the extra playing RFK into the kitchen, Emilio staged it as if it were all the footage we had. And starting with the sequence of RFK entering the kitchen, Michael increased the movement of his handheld camera so it became very erratic and unpredictable. We found archival footage that had a similar feel. Once I found a way to stitch it all together, the emotion of the scene carried us past the mismatches and it worked out really well.

CM: Since there must have been a lot of video and film of the shooting and its aftermath, how did you determine how much of it to use?

RC: There were some classic raw moments in the archival stuff. We initially used much of it, throwing it into the last ten minutes. But at one of the previews, we found that we went overboard and had too many archival shots––like in front of the hotel when the real Bobby was being put into the ambulance. It hit us that we were trying too hard, so we pulled some of that stuff back.

CM: What about the speech that was used over the final sequence? How was that selected and edited?

RC: First, we chose not to feature his victory speech at the Ambassador that night because it was a political nuts-and-bolts speech thanking his supporters. We used it only tangentially. Instead, we featured an eloquent speech made only two months before, which he gave a few days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. It was eight minutes long, so we couldn’t use the entire text, but we kept the linear structure of the speech and moved it around in a way that would open up space for the musical statements that composer Mark Isham was creating.

CM: Do you feel you learn something with each new show?

RC: I like to think that I learn from certain pictures because of the subject matter of a particular story. Also, in the last 10 or 15 years of my career, I’ve learned how to better relate to a director. Maybe it’s just a wisdom that comes from experience, but I truly believe in the collaborative process, and that’s why I like the challenge of working with different writer-directors. Cameron Crowe is different from Paul Brickman who is different from Tom Hanks who is different from Emilio Estevez. I welcome the stimulation of working with filmmakers of different sensibilities. That’s why I like to mix it up.

CM: What will you take away with you from this experience?

RC: My very special relationship with Emilio Estevez. He showed me how hard it is to transform your own vision to the screen. He developed this project himself; he was not a director for hire. It was his vision that carried this project through. He suffered from limitations of budget and staff. He suffered from lack of support from important quarters. Yet he persevered, and made a memorable piece of work. I’m lucky we found each other for Bobby.

CM: And finally, the burning question: In Star Wars, did George Lucas name Chewbacca after you?

RC: I never had the nerve to ask George––just because I would be embarrassed if he were to say no. However, I like to entertain the illusion!