by Edward Landler

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.

— Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952)

Over the decade leading to 1973, with the progress achieved by the civil rights movement, a greater awareness emerged in the African-American community of its own history and culture. Despite this growth of self-worth, pride and initiative giving strength to the idea of Black Power, the systemic practice of inequality and oppression of minorities continued to afflict American society — just as it has become obvious that it persists to this day.

The years following the 1963 March on Washington witnessed spontaneous civil unrest in our cities, along with the persecution and assassination of figures who offered insight and effective leadership: Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and Chicago Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. Like today, adding fuel to protest and political action was this country’s involvement in questionable wars overseas against people of color.

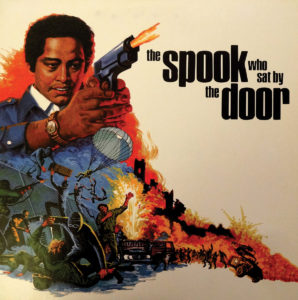

On Labor Day, September 3, 1973, 45 years ago, United Artists quietly premiered The Spook Who Sat by the Door, a movie reflecting these issues, at the Maryland Theatre in Chicago’s South Side. With a story shifting from pointed political satire to the plausible nurturing of a black rebellion, it was independently produced by its director, Ivan Dixon, and Sam Greenlee, who wrote the original novel and co-wrote the screenplay with Mel Clay.

Greenlee’s friend, Colostine Boatwright, an actress who played a dancer in the movie and later appeared in Cooley High (1975), told CineMontage, “Sam insisted that it be screened first in his own neighborhood.” Within a week, Mayor Richard Daley’s office, which had denied location permits for the movie to be shot in Chicago a year earlier, pressured local movie houses to pull it from exhibition or face city inspections.

Over the next four months, though, UA arranged a 21-city tour for Spook as a “blaxploitation” movie in black neighborhoods. The trailer proclaimed that its main character “was for five years [the CIA’s] token Negro and, when he got out, he turned ghetto kids into a revolutionary army!”

At the end of September, according to a UA press release, it had grossed “an excellent $361,636 in 13 cities…$40,836 in its first three days at the DeMille and Juliet Theatres in New York.” In the National Association of Theatre Owners’ BoxOffice magazine, a review noted, “It effectively mirrors the increasingly strained black-white relationship.”

Before Spook’s December 19 Los Angeles theatrical opening, the movie was welcomed to LA with an October 29 benefit premiere at the Fox Wilshire Theatre, sponsored by the Hollywood Civil Rights and Education Foundation and the National Association for Sickle Cell Disease, and hosted by vocalist Nancy Wilson and actor Greg Morris (Mission: Impossible, 1966-1973).

But before the end of the year, The Spook Who Sat by the Door vanished from the screen. In a 2011 interview with media studies academics Michael T. Martin and David C. Wall, published in the 2018 book Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” (along with essays and the full screenplay of the movie), Greenlee said he believed that UA “pulled it off the market at the behest of the FBI.”

The distribution prints were all destroyed, but the producers retained the rights to the movie and Dixon vaulted the original negative under a different name. Over the next 20 years, a few bootleg VHS copies circulated, bringing it a reputation as an “underground black classic,” but it remained unknown among general audiences.

In 2001, Dixon and Greenlee gave the negatives to actor/producer/director Tim Reid, who digitally remastered them and released the film as a DVD in 2004 through his Obsidian Home Entertainment. In a January 20, 2004 New York Times article, Dixon said, “Spook was only trying to show black anger, not suggest armed revolt as a credible step.” He passed away in 2008.

With the cooperation of Greenlee, Dixon’s widow Berlie Dixon and others closely involved with the movie, filmmakers Christine Acham and Clifford Ward in 2011 produced Infiltrating Hollywood: The Rise and Fall of “The Spook Who Sat by the Door,” a documentary about its making and disappearance from public view. The following year, in 2012, the Library of Congress named Spook to the National Film Registry, established to ensure the preservation of films that are “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

The movie’s significance begins with the novel. After graduate school, Greenlee served as a foreign services officer for the United States Information Agency in Iraq, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and Indonesia. His experience in post-colonial nations, he told Martin and Wall, convinced him “that the instruments of imperialist domination…segregation, discrimination…were identical to those utilized in the oppression of Black America.”

Greenlee returned to the US in 1965, just as the Watts Riots broke out. In Infiltrating Hollywood, he stated, “You saw riots. I saw them as rebellion… The Spook is a handbook on urban guerilla warfare…to encourage blacks to create an action plan to survive in the belly of the beast rather than reacting as victims of a racist society.”

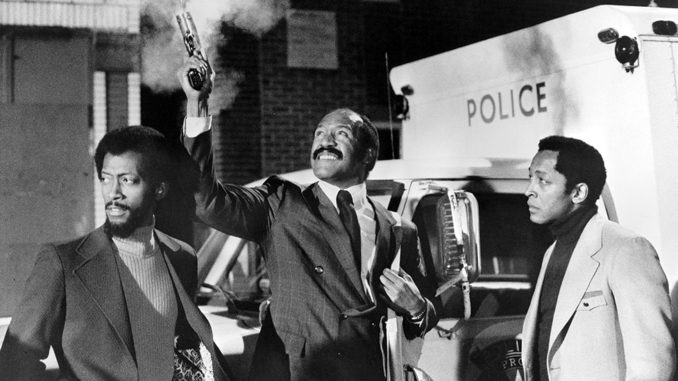

This perspective became that of Dan Freeman, the novel’s lone black CIA agent. After training and serving five years as “window dressing” at agency headquarters, he resigns to turn Chicago’s Cobra gang into the Black Freedom Fighters. In the movie, Freeman (played by Lawrence Cook) tells them, “What we got now is a colony. What we want to create is a nation.”

Rejected by more than 40 American publishers, the book was published in the UK in March 1969 by a firm founded by Clive Allison and Ghanaian-born Margaret Busby. It became a best seller and received “Book of the Year” mentions from London’s The Sunday Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Irish Times. The book was published later that year in New York by Richard W. Baron Publishing. When a review was featured on WNET’s Soul! (1968-73), a black public affairs show, Greenlee’s story was brought to the attention of the African-American community.

In 1970, the writer adapted his book into a screenplay with the help of Clay, a former member of the experimental Living Theatre, who said in Infiltrating Hollywood, “The novel was as cinematographic as it could get.” Later that year, in Hollywood, Greenlee went to the set of TV’s The Mod Squad (1968-1973) to talk to series star Clarence Williams III about playing Freeman, and met Dixon, a guest star in the episode then being shot.

Rising to film prominence supporting Sidney Poiter in Porgy and Bess (1959) and A Raisin in the Sun (1961), and starring in Michael Roemer’s seminal independent Nothing But a Man (1964) with Abbey Lincoln, Dixon was leaving the World War II POW sitcom Hogan’s Heroes (1965-1971), which was going off the air. He had read Greenlee’s novel and wanted to direct it. In Infiltrating Hollywood, his widow recalled him insisting, “I’ve got to make this movie.”

Neither Dixon nor Greenlee wished to compromise the story to get studio backing, and they formed a partnership called Bokari, Ltd. Over the next three years, they raised $850,000, mostly from black investors, while Dixon built a resume directing TV and a black detective feature, Trouble Man (1972).

United Artists/Photofest

Assisted by attorney Thomas Neusom, Greenlee’s University of Chicago graduate school classmate, Greenlee and Dixon’s fundraising continued through Spook’s post-production. Chicago-based actor and casting director Pemon Rami, who also worked on Cooley High and The Blues Brothers (1980), explained to CineMontage, “The book created a community of support for its expression of what all blacks have experienced in American society.”

This was also true for crew and cast. Early in her career, the 2017 recipient of the Set Decorators Society of America’s Lifetime Achievement Award, Cheryal Kearney (Poltergeist, 1982; Coming to America, 1988), brought African artwork to Spook’s apartment sets. She told CineMontage, “When I read the script, I saw how important that was…and that the producers were trying to get as many blacks on the crew possible.” Spook’s camera operator Joe Wilcots, the first African-American camera operator in Local 600, later became a DP on Roots (1977) and Roots: The Next Generation (1979).

The film’s complex portrayal of the divisions within African-American society itself motivated the actors. J.A. Preston (Body Heat, 1981; A Few Good Men, 1992), who played the cop working within the established system, noted for this article, “All of us had read the book and we didn’t expect that it would be a movie… Everybody was doing it at minimum wage.” Rami added that many in the cast brought their own clothes for wardrobe throughout the shoot.

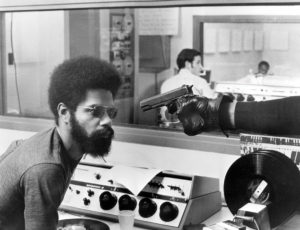

Despite a lack of location permits, production began in Chicago, shooting on and off with a skeleton crew and handheld camera equipment over two weeks in October 1972. In an interview appearing on the movie’s 2004 DVD, Greenlee admitted, “All the scenes in Chicago were…shot guerilla-style…like the shots from the ‘El’ platform at 63rd and Planters Row in the neighborhood where I still live. We just paid and went through the turnstile.”

In contrast, the city of Gary, Indiana opened its arms to the entire company for three weeks in November. Richard Hatcher, the first African-American mayor of the city, had read the book and put everything at Dixon’s disposal: A two-block section of a neighborhood resembling Chicago’s South Side, the fire department and the police department, including its helicopter. All of this would be especially crucial for the movie’s riot scene, which provided temporary employment as extras for up to 500 residents.

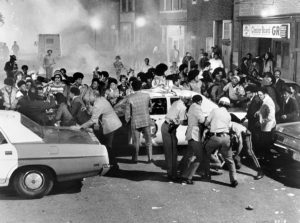

Prefiguring recent events in US cities, the final third of Spook begins with Shorty (Rami), an unarmed junkie, being shot and killed running from the police. A neighborhood protest explodes into violence when police bring dogs to the scene. Deploying handheld cameras over a day and a half, DP Michel Hugo, ASC (who also shot Trouble Man), captured more realism than expected. As Preston described it, “Some of the extras got carried away with the action; they even turned over a police car and set fire to it. That wasn’t scripted.”

Filming was completed over two weeks early in December in Los Angeles, where the footage was already being edited by future three-time Oscar winner Michael Kahn, ACE, five years before he began his long collaboration with Steven Spielberg. He and Dixon had become friends over the years that they both had worked on Hogan’s Heroes, and he also cut Trouble Man. Assistant editor on both Trouble Man and Spook was Thomas Penick, who went on edit Charles Burnett’s My Brother’s Wedding (1983).

“I was editing what Ivan sent me as he shot, and he came whenever he could,” Kahn commented to CineMontage. “It didn’t feel faked. On the stronger scenes, I went for the jugular; I liked the handheld shots in the riot scene… The story in the novel and the script was well told, and I enjoyed the message.”

While editing continued into early 1973, Greenlee’s community roots enabled him to find music for Spook. Like him, Chicago documentary filmmaker Bernard Williams, who had helped with the Chicago guerilla-style shoot, had attended Hyde Park High School, as had jazz keyboardist Herbie Hancock and Hancock’s sister, Jean, who was a close friend.

Williams informed CineMontage, “Jean set up a meeting with me and Herbie. He knew Sam and he knew the book and he put together a recording of a variety of original compositions that Sam could use as he pleased in The Spook.” Hancock’s music for the film strongly reflects the innovative electronic sounds and funky rhythms that were evolving into his best-selling album Headhunters, released in late 1973.

Meanwhile, in LA, Dixon shopped a 10-minute trailer of the movie’s action scenes around to the studios. Thinking they had a hot ‘blaxploitation’ picture, UA put up $150,000 to complete post. Greenlee told Martin and Wall, “When they saw the final cut, they were outraged. I said, ‘You required six copies of the script. Don’t blame me if y’all can’t read. We’ve got a damn contract!’” In accordance with that contract, UA released The Spook.

In 1975, in Alexandria, Virginia, Bokari Ltd. filed a civil action suit against 13 prominent intelligence figures, all currently or previously officers in the CIA or NSA. In the suit, Dixon, Greenlee and attorney Neusom claimed, “…[T]he CIA and the NSA defendants, by colluding and conspiring with United Artists did bar the plaintiffs’ motion picture…from viewing houses…because of the content of the picture which they adjudged objectionable.” The suit also alleged, “…[O]n or about and after November 28, 1973…the CIA and NSA defendants communicated with United Artists regarding the release and distribution of the picture…,” and went on to state, “[A]s a direct and proximate result of said actions by the defendants, plaintiffs have and are suffering grievous financial injuries, all to their damage in the sum of 50 million dollars.”

CineMontage has been unable to determine the results of the suit, or if it was ever heard, settled or decided.

Nevertheless, as the late actor Paul Butler (who portrayed the Cobra/Black Freedom Fighters leader and, in 1990, the family patriarch of Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger), pronounced in Infiltrating Hollywood, “The Spook Who Sat by the Door is the most political film of the ‘blaxploitation’ era, and maybe one of the most political films that’s come out of Black America… The spirit on the set was basically one of rebellion and defiance.”

The last word remains with Greenlee, who died in 2014. On the 2004 DVD release, he stated, “I’m not trying to recruit, proselytize or convince anybody. I want to shake up ‘the Man’ and people to look at that movie and go out of there thinking — and I think I’ve accomplished that purpose.”