by Bill Desowitz • portraits by Deverill Weekes

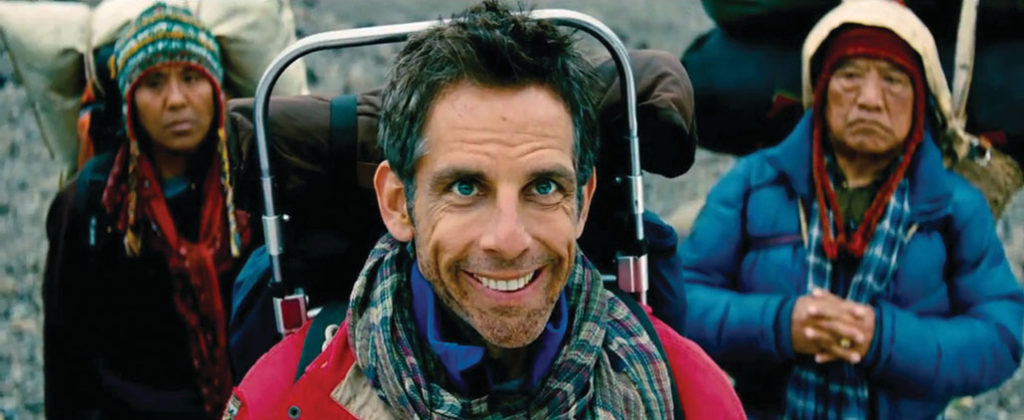

The first time that Greg Hayden, A.C.E., watched Ben Stiller as Walter Mitty on the Avid in his edit bay, he knew this was going to be a different kind of film for the actor-director. It certainly wasn’t Zoolander or Tropic Thunder, the broad comedies he previously cut for the actor-director. This was more like The Apartment or Being There (maybe that’s why Stiller cast Shirley MacLaine as Mitty’s sweet and sensitive mom). Stiller’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty opens Christmas Day through 20th Century Fox.

“The first day of dailies was Walter leaving his apartment and heading for work,” recalls Hayden, who has cut several hit comedies in the past dozen years, including a couple starring but not helmed by Stiller. “His whole manner was quiet and still; his character was more subtle and nuanced. The way Ben framed all the shots had a different tone and sensibility. Even the main titles are part of the scenery.”

Hayden especially likes how the film opens with Mitty in his apartment, frustratingly trying to leave an e-Harmony “wink” for a girl named Cheryl (Kristen Wiig), who turns out to be the co-worker he secretly adores. “I think it sets his character up as well as hints how he’s going to transition,” the editor says. “He’s an analog guy living in a digital world.”

Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

Indeed, that was the 21st-century hook in remaking the classic 1939 James Thurber short story for the big screen (while distinguishing it from the beloved 1947 comedy starring Danny Kaye). Stiller, who worked with screenwriter Steven Conrad on the remodel, was enticed by the notion of the eternal daydreamer grappling with social networking, downsizing and the paradigm shift from old media to new media.

The breakthrough was setting Walter Mitty at Life magazine just as it’s transitioning from print to online. The gentle yet hardworking Mitty is the negative assets manager, the little guy behind the scenes preserving our cultural photographic heritage. “Shooting on film was important,” Hayden explains. “Film is going away and Walter is the caretaker of pictures shot on film.”

When he is tasked with handling the final cover photo, Mitty discovers that the negative is missing, so he embarks on a journey to find the reclusive photographer (played by Sean Penn) and fulfill his duty. This, of course, forces him out of his comfort zone in New York City and on a fantastical adventure that takes him from Greenland to Iceland to Afghanistan (the use of widescreen enlarges the scope as well). He dives into shark-infested waters, scampers into a volcanic eruption and scales the Himalayas.

For Hayden, this meant balancing Mitty’s fantasy life with his real-world experiences, delivering a seamless flow between the two while also integrating different looks (intimate, action-packed, exotic) and graphics emerging from the landscapes.

“When I read the script, it immediately resonated, and Ben and I discussed The Apartment, Being There and The Graduate in terms of tone and sensibility,” Hayden continues. “I thought all the fantasy would be interesting but easy.”

But the most elaborate fantasy sequence was far from easy. It begins with a heated encounter in an elevator between Mitty and his bearded, snarky boss, Adam Scott from Parks and Recreation, and then transforms into a flying street battle in mid-town Manhattan. The fantasy is over-the-top in poking fun at the superhero genre but, as Hayden suggests, it gives us great insight into what’s going on in Mitty’s head.

“We didn’t have effects yet,” Hayden explains. “But we had previz that we were following and they were running through the streets on roller skates and a skateboard. You have to imagine them in those concrete slabs and work out the weight in terms of how you would cut it. The sequence started out longer, but was trimmed to two minutes. What we found out with all of the fantasies is that they work better shorter. Walter’s real trials and tribulations were more compelling than his fantasy life.”

However, the editor was also worried that the story might not be as interesting when the fantasies ended. But he was pleased when the opposite happened, and he worked diligently on maintaining a balance between fantasy and reality.

For instance, he and Stiller established a slower pace at the beginning, with Mitty trudging along. The camera is more static and the compositions more formal. “We tried to hold on takes for as long as we could,” Hayden reveals. It was almost like snapshots from the magazine — a still life.

One of the editor’s favorite moments is when Mitty’s mother tells him how his role is vital to the famed photographer: “You finish his work.”

“When Mitty starts getting more out into the world and experiences a real-life adventure, the camera work becomes freer and more hand-held, and the cutting pace quickens,” Hayden explains. “We changed the tone of Teddy Shapiro’s score and started using more songs [David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” serves as a thematic thread]. We also thought that Walter’s fantasies should be jarring for him, so we worked on the transitions in and out of those. We wanted a jarring snap back into reality.”

As the movie progresses, in fact, there’s a blurring of fantasy and reality — such as when Mitty leaps into a helicopter to go to Iceland, and jumps into the water and is nearly killed by a shark.

“That’s why I like the ‘Major Tom’ [“Space Oddity”] sequence with Cheryl,” Hayden says. “It’s hard to tell whether it’s fantasy or reality, yet it’s the linchpin that gets him on the helicopter and drives him forward. Is the shark scene a fantasy or reality? We don’t know until he touches a man’s face.”

“Ben is never precious about anything, and so we just did a lot of experimenting… We sped it up, we slowed it down. We played around with Walter and Cheryl’s relationship. How intense should it be at the beginning? We didn’t want her to be too interested, and we didn’t want it to be too easy for him.” – Greg Hayden

The fantasies serve another purpose, too: They foreshadow what happens to Walter in his real life. “There’s the alpine fantasy, where he’s a mountain climber and actually ends up doing that to catch up with the photographer,” Hayden continues. “He also skateboards down a mountain.”

During production, as soon as Hayden had a scene ready, he sent it to Stiller to discuss what was working, what wasn’t, how the story was progressing and what needed clarification. With Mitty, since it was a dramedy, the goal was mainly about achieving naturalistic performances.

This definitely goes against the broad humor of Stiller’s most recent feature directorial efforts, generating laughs from looks instead of punch lines. According to Hayden, Stiller still makes Mitty very relatable when living inside his head because he’s trying to make emotional connections with people and places outside of his comfort zone.

“On Mitty, I feel Greg understood Walter and was always searching for performance in takes that were sometimes the difference in how a scene landed,” Stiller remarks. “He was really the one who shaped that performance, with the goal of telling Walter’s story in a way the audience could follow.”

“Ben is never precious about anything, and so we just did a lot of experimenting,” Hayden says. “We sped it up, we slowed it down. We played around with Walter and Cheryl’s relationship. How intense should it be at the beginning? We didn’t want her to be too interested, and we didn’t want it to be too easy for him. We adjusted non-verbal interaction — a lingering look here, a reaction there. We massaged her reaction shots to show that she’s interested but not too eager.”

Hayden admits that he and Stiller worked very hard on all the reaction shots in their pictures together. “I think that’s where the comedy is,” he maintains. “I loved the reaction shot when Walter discovers that he’s thrown the negative away. And Sean Penn has a great reaction to meeting Walter. There are subtle moments that are different from take to take, but they were all good. I was surprised that Sean had such great comedic timing; you don’t associate that with Sean Penn.”

Courtesy of 20th Century

One of the scenes that turned out to be a pleasant surprise for Hayden was with a drunken pilot (Ólafar Darri Ólafsun) in Greenland. He’s such a quirky character, but he’s lonely and Walter immediately connects with him. Plus, we hardly ever see Greenland in movies.

“Ben’s got good instincts on set about what’s working and not working, and will often shoot different versions of a scene [shorter or with different blocking or different lines],” Hayden reveals. “A big section we played around with was the Afghan trek. It was conceived as a voiceover, where Walter describes his search for Sean Penn’s photographer. But I never thought it worked as a device because it’s the only time we use voiceover.”

The voiceover also distances us from the immediacy of what Mitty’s experiencing. That’s when Hayden and Stiller hit upon the idea of using graphics to depict what he’s writing in a travel journal given to him by his late father — and that’s when the sequence came to life, dramatically speaking.

The other endearing relationship in the film is the one between Mitty and his e-Harmony customer relations rep (Patton Oswalt), who tries to bolster his application so he can find a suitable match. They have an amusing series of phone conversations — usually at the most inopportune times — but as Mitty becomes more of a wild adventurer, the rep turns him into one of e-Harmony’s hottest stars. Eventually, they meet at Los Angeles International Airport, when Mitty gets into a jam and it becomes another way of connecting with someone in person.

According to Stiller, there is no one he trusts more than Hayden, who’s not only technically proficient and fast, but who also has “an almost brutally honest sense of humor and story. He will always give me his real opinion — even in situations where I might wish it were different,” the director says. “I think that ability to have a point of view is essential in the cutting room. It helps that we have a very similar sensibility as to what is good or funny.”