By Peter Tonguette

If it is true that Hollywood loves movies about itself, then the movie industry ought to be in a state of ecstasy over Damien Chazelle’s new film “Babylon.”

The much-talked-about Paramount Pictures release, which derives inspiration from numerous personalities, incidents, and events from 1920s-era Hollywood, is like three or four Hollywood movies rolled into one. In one of multiple storylines that intersect, overlap, and spill into each other, Brad Pitt stars as Jack Conrad, a stalwart silent player whose popularity begins to slip when talkies take over. Also starring are Margot Robbie as Nellie LaRoy, a go-getting wannabe actress whose lack of training — and copious party-going — are no impediment to her own stardom; and Diego Calva as Manny Torres, a Mexican American man who makes the unlikely progression from largely ignored gofer to respected studio executive.

In an epic that unspools over some 3 hours and 9 minutes, Chazelle finds room to incorporate references to the Fatty Arbuckle scandal, the premiere of the first talkie, “The Jazz Singer,” a famous early attempt at filming the musical number “Singin’ in the Rain,” and the outsize importance of gossip columnists, the latter embodied in the film by movie journalist Elinor St. John (Jean Smart). Watching — and often providing musical accompaniment to — the dizzying goings-on is yet another leading character, a Black jazz musician named Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo) who aspires to be part of Hollywood but, in time, finds he must walk away from it. Imagine an adaptation of Kenneth Anger’s nonfiction book “Hollywood Babylon” — the experimental filmmaker’s notorious chronicle of the underbelly of the picture business — as directed by, say, Robert Altman. That’s “Babylon.”

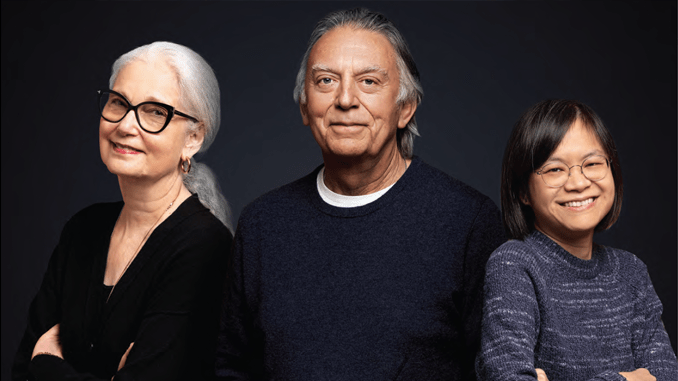

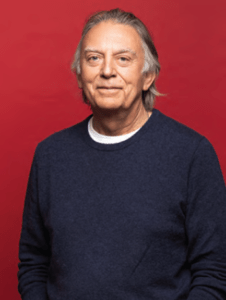

As the post-production team explained in recent interviews with CineMontage, the mandate from Chazelle was simple. “Damien always wanted to have this movie be very maximalist in every single way,” said picture editor Tom Cross, ACE.

Said supervising sound editor Mildred latrou: “Controlled chaos.”

“That was kind of how it felt all the way through, just working on it, because there were so many elements and so many decisions that had to be made,” said re-recording mixer Andy Nelson, CAS. “The overall approach . . . was just bold and out there.” Added supervising sound editor, sound designer, and re-recording mixer Ai-Ling Lee, CAS: “[Chazelle] wanted the sound to feel real and visceral and larger-than-life.”

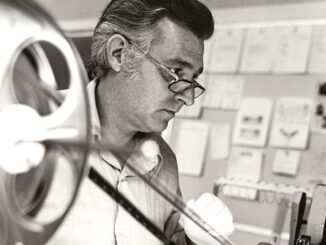

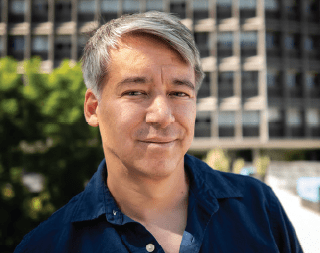

For Cross, “Babylon” represented an altogether different kind of project with his longtime collaborator Chazelle. Their previous films — the music-school drama “Whiplash” (2014), for which Cross won the Oscar for Best Film Editing; the musical “La La Land” (2016); and the Neil Armstrong biopic “First Man” (2018) — were each ambitious, each difficult in their own way, but also fairly streamlined. “‘Whiplash’ and ‘La La Land’ were really two-handers, and ‘First Man’ was a single-character portrait in a way,” Cross said. When he read Chazelle’s 180-page script for “Babylon,” however, the editor knew the scale of the film would be unapologetically vast.

“He wanted to show this version of Hollywood that existed during the silent era, these wild roller-coaster days, and show that world through the perspectives of different characters,” Cross said. “We wanted to make sure that all the characters had their own arcs.”

Added Cross: “It may be the hardest movie I’ve ever worked on.”

The challenge for Cross was in not shortchanging any one character’s story. When cutting most movies, the editor has found that it’s possible to boil a story down in post-production without losing anything essential, but if that approach had been taken in cutting “Babylon,” someone’s story — Jack’s, Nellie’s, Manny’s, or Sidney’s — might be compromised. “On ‘Babylon,’ you can only boil down so much until you start taking away character arcs or character beats,” Cross said. It’s another way of saying that “Babylon” could have been about just Jack, Nellie, Manny, or Sidney, but as Chazelle saw it, it had to be about all of them — and at feature-length.

At the same time, Cross added, Chazelle had no desire to make a film that was slow, meditative, or contemplative. “Babylon” had to be stuffed with characters and action — and to be constantly whirring, buzzing, humming. “He wanted it to be driving,” Cross said. “He wanted it to feel like ‘The Wolf of Wall Street.’”

The tone is established in the film’s opening minutes with an audacious party scene featuring the principal characters converging at a mansion somewhere in Southern California. There is sex, drugs, drinking — the whole works. More than 30 minutes has elapsed before the appearance of the title card, a strategic decision on the part of the filmmakers. “Damien always intended the opening to be an introduction, but it was always designed to be a very lengthy introduction,” Cross said. “By the time you get to the title card, Damien really wanted the audience to be reminded that: ‘Oh, we’re just getting started. We need to buckle up for an epic ride.’”

During the opening scene, the audience is confronted not just with Hollywood at its most sordid but also with music — some of it period-appropriate, much of it pushing boundaries: jazz is heard along with hip-hop beats and even techno beats. “Damien wanted to smash all of the audience’s preconceived notions about what a 1920s period piece would be,” Cross said. That included the volume of the music. “Damien wanted this thing to come in like a storm and just carry you through the sequence,” Nelson said. “It was a question of me really setting a music level and then inching it up even more each time. We wanted to see how far we could go before we broke it, to get that complete sense of overwhelming musical style.”

Dialogue had to shine through the cacophony. “The only spot where there is production dialogue, everybody is talking at the same time,” latrou said. “We worked with the great dialogue supervisor Susan Dawes, and she and I had this incredible challenge of having these simultaneous conversations [and] making sure they were as clean and clear as possible so that we could manipulate during the mix.”

In fact, the party scene was among the first that was cut; in a departure from his usual working methods with Chazelle, Cross edited “Babylon” starting at the beginning. “Usually when Damien and I work together, . . . we always start editing at the end, so in the case of ‘Whiplash,’ we started with the ‘Caravan’ musical number at the end,” Cross said. “On ‘Babylon,’ he made the decision for us to start at the beginning because he felt that the movie was so vast — where we end up at with our characters, and stylistically, is very different from where we start.”

By marching through the material in this manner, Cross gained an appreciation for the wide variance of tones throughout the movie. Set pieces notable for their loudness and brashness, such as the opening party, alternate with far subtler and quieter passages. “If he wants to come out of the gate with the loudness playing up at eleven, he knows that that will be extra loud if you bookend it with things that are at zero,” Cross said. “As an editor, that’s very exciting because he builds in these peaks and valleys.” For example, somewhere in the middle of the movie comes a long sequence in which Jack (Pitt) pays a visit to the office of journalist Elinor St. John (Smart). In a scene that unfolds in long close-ups of the two performers, Elinor candidly assesses the state of Jack’s career. “My goal for a sequence like that is to really stay out of the way,” Cross said. “What you’re left with are characters interacting, eyes meeting or not meeting. You’re left with faces and expressions.”

If ever a movie can be said to contain multitudes, “Babylon” is that movie. Certain scenes were cut to reflect the style of various classic movies, especially those from the silent era. For example, one long sequence with several storylines unfolding concurrently — on location in the desert while multiple silent movies are being shot, Nellie makes her first (memorable) appearance in front of the camera, while Manny, working on another production, has been tasked with tracking down a usable camera from a camera rental shop in town — was cut using classical editing techniques. “He wanted to feel the excitement of the parallel editing you have in [D.W. Griffith’s] ‘Intolerance,’” Cross said. On the other hand, a battle scene in one of the movies-within-the-movie was cut like something out of Sergei Eisenstein. “It was Damien’s intention to play with cinematic language in that way,” Cross said.

Another scene echoes an already legendary scene from Chazelle’s own “Whiplash”: Playing a co-ed in her first talkie, Nellie is seen, again and again, walking onto a soundstage to deliver a line: “Hello, college.” Each time, though, something defeats her: she stands in the wrong spot or speaks in such a way that doesn’t register on the primitive microphones. The repetitive series of actions becomes hypnotic: the slate boy noting the take number, the director motioning her hand to signal action, the clomping of Nellie’s shoes, the thud of Nellie’s luggage hitting the floor. And then that line: “Hello, college” — again and again. (If the sound of the scene seems to quicken as it unfolds, it’s not your imagination: “As the scene keeps going, each of the repeated steps starts getting a little shorter and faster,” Lee said.)

Sound familiar? “Damien and his producer, Matt Plouffe, always referred to that section as the ‘Whiplash’ section, . . . because it reminded them of the ‘rushing and dragging’ scene from ‘Whiplash,’” Cross said.

In “Babylon,” the repetition leaves the audience wondering what will go wrong next. Will Nellie hit her mark? Will she speak loudly enough, or clearly enough? In other words: is Nellie rushing, or dragging, so to speak? “The idea was to play around with the audience’s expectations and create suspense that way,” Cross said. “Each time we cut to this preamble, we cut it faster. You’re trying to create momentum and you’re trying to create a rhythm, and the hope is that by the time you get to the end of the sequence, you have synchronized the audience’s heartbeat with the rhythm of the cutting. The hope is that the audience will feel in their gut that there is a kind of mechanical march toward doom.”

A mechanical march toward doom — it’s not a bad description of the trajectory of most of the characters in “Babylon,” each of whom is compromised, in ways big and small, by the industry they so desperately wish to be part of. “All the characters get transformed by Hollywood in their own way,” Cross said.

Yet, for a film as long and purposely ungainly this one, “Babylon” did not get transformed in fundamental ways during post-production. The first assembly, clocking in at 2 hours and 56 minutes, was about 15 minutes shorter than the release version. “We actually worked really hard to try to bring the time down just as an exercise to see how fast we could make it,” Cross said. But that cut was just too fast. Cross’s next cut was far more loose-limbed at about 3 hours and 30 minutes. Then the movie was pared down first to 3 hours and 15 minutes and, finally, to the present length. “We found that the movie ended up really where it wanted to be,” Cross said. The glue that helped hold the movie together, Cross said, was the score by Justin Hurwitz. Because the composer fashions melodies and score ideas in advance, Cross had the luxury of working with the score as he was cutting. “By the time I start getting dailies, Justin has already mapped out rough demos of what the score will be,” Cross said. “I’m never cutting with any other temp music; I’m always using Justin’s score, and I’m cutting directly to his score.”

Nelson also credits the score with adding much to the movie, sometimes almost imperceptibly. “Justin’s score is extraordinary because it is repeating things, it’s using themes that he creates, but often in a very different way, a completely different tempo, stripped down, very simple at times.” Jason Ruder was the supervising music editor and Lena Glikson the music editor.

Bookending the party with which the film opens was an equally shocking scene in the final stretch: In trying to settle a debt incurred by the increasingly reckless Nellie, Manny pays a visit to the vast compound of movie-bewitched mobster James McKay (Tobey Maguire). There, Manny and a colleague are invited to a kind of underground lair full of unsettling sights and sounds. “It is a descent into hell,” Cross said, but a hell that is experienced impressionistically. “The goal was to get glimpses of the crazy stuff that was going on down there, but also have that glued together by the music you’re hearing and the sonic landscape that sound department gave us,” he said.

Indeed, the scene disturbs partly for what is glimpsed — spoiler alert: a rat is consumed — but, just as much, for what we think we hear. “The first time I read it in the script, I thought, ‘That’s like a whole other palette of sounds that we need for the film,’” Lee said. “Damien wanted it to feel like, for each level as we go, we need to create that anticipation and fear of the danger as we’re going further and further down. All the crowd, the chanting, they just need to sound more menacing in order to feel like we are really stuck in close space with them and there’s no way out.”

Yet “Babylon” concludes on a strangely hopeful note: In 1952, Manny, having left Hollywood and seemingly adjusted to life away from the business, checks out his old studio. Then he buys a ticket to a showing of one of that year’s great hits, Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s masterpiece “Singin’ in the Rain.” This prompts flashbacks from “Babylon” itself as well as a kind of grand summary of film history. As if Manny has absorbed all of film history to that point — as well as film history yet to come — Chazelle and Cross offer a nearly psychedelic montage of memorable snippets from a huge variety of movies. “One of our big inspirations for that sequence was the Stargate sequence in [Stanley Kubrick’s] ‘2001,’” Cross said. “The emotion was always there in Damien’s script, but that was a sequence that Damien and I created in the editing room. Damien really wanted to end on something much more experiential than what we originally had.”

So what’s the takeaway? The film suggests that Hollywood was always a vicious, cruel, immoral place — but it also birthed a great art form.

As Cross sees it, the movie’s message is a bit humbling. As the editor was reading about the silent era, he was struck by how many of the era’s big stars or blockbusters were unknown to him. “It reminded me that there may come a time when people simply do not remember a movie that you’ve worked on, or may not remember a big movie star who was in it,” he said. “I’m just another editor, and I’m just another person whose name is sitting in a crawl.”

Even so, the impressive post-production achievement on “Babylon” assures that Cross and his colleagues won’t be forgotten any time soon.