By Peter Tonguette

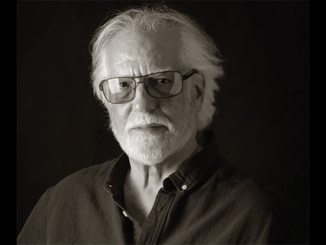

Milton Moses Ginsberg, a pioneering independent film director who maintained a career-long sideline as a picture editor, died May 23 at the age of 85.

The Bronx native and longtime New York resident is most widely associated with the stark, daring, and highly original feature film he wrote and directed some 52 years ago: “Coming Apart,” which premiered in October of 1969, starred Rip Torn as Joe Glazer, a psychiatrist who surreptitiously films female visitors to his apartment. The black-and-white film is presented from the perspective of Glazer’s static hidden camera.

“Milton Ginsberg was my friend of many years — a superb editor of documentaries, he was also a filmmaker with a unique vision of the world,” Motion Picture Editors Guild president Alan Heim, ACE, told CineMontage. “‘Coming Apart’ was a tour-de-force of truly independent film which should be seen by everyone, and ‘The Werewolf of Washington,’ which followed it, is a treat.”

Although Ginsberg was influenced in part by the avant-garde films of Andy Warhol, the film’s depiction of a protagonist who uses technology to cope with a confused romantic life anticipates confessional films such as Steven Soderbergh’s “sex, lies and videotape.”

Upon its release, “Coming Apart” received admiring reviews from leading critics, including Gene Siskel and Richard Schickel (the latter of whom called it “one of the few illuminating — not to say harrowing — portrayals of a schizophrenic crackup that I have ever seen on the screen.”)

“Joe Glazer comes apart in a series of sexual confrontations with as diverse (and ultimately as bleak) a group of partners as you’re likely to see in a year of field trips to movies on 42d Street and Eighth Avenue,” wrote New York Times critic Vincent Canby in his original review.

Despite such notices, Ginsberg said that a single dismissive review from influential Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris led to the film’s ultimate failure with audiences. “That was it,” Ginsberg told the New York Times in 1998. “No agents called. I had done everything I wanted to do. And nothing happened.”

It had already been a long road to filmmaking for Ginsberg: A graduate of Columbia University, where he majored in literature, Ginsberg was hired as an apprentice editor at NBC News. “They were establishing a documentary unit along the lines of Leacock, Pennebaker, and Maysles,” Ginsberg told the website Screen Slate. “I was an apprentice on a kid’s show in that unit, and the editor started giving me more and more work to do. He saw that I was very capable. He said, well, I’m going to treat you as an assistant not as an apprentice.”

Ginsberg began writing original screenplays, several of which were optioned. “I used to use the library in the Metropolitan Museum to go in and write, because there’d be people around, but you couldn’t talk,” he told Screen Slate. “It comforted me, having company, in a manner of speaking.”

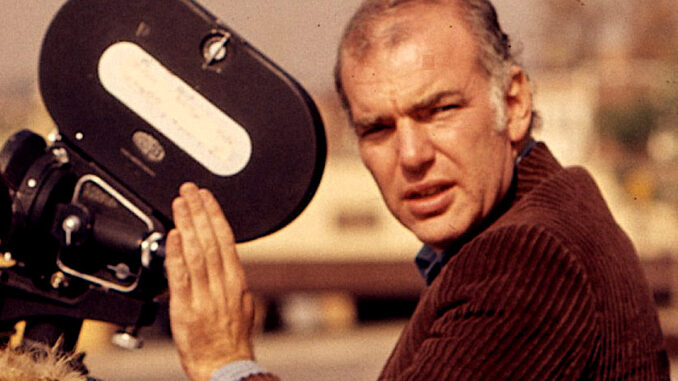

Then came “Coming Apart,” which, while never destined to become a popular hit, left an impression on those who saw it, including director Jim McBride, whose own film, “David Holzman’s Diary” (1967), was an influence on Ginsberg.

“I went to see it in one of those screening rooms on Broadway,” McBride told CineMontage, remembering his first viewing of “Coming Apart.” “I didn’t know anything about it, and I can’t remember how I was invited, but I found myself sitting a couple of rows behind Bob Dylan, and I was so impressed, so excited to be in his presence, and so jealous that he would come to see this movie, while probably not knowing anything about mine, that I was barely able to focus on the film itself.”

Ginsberg managed to write and direct another independent feature, “The Werewolf of Washington” (1973): The political satire starred Dean Stockwell as a press secretary at the White House who moonlights as a werewolf.

“There are so many scripts he wrote that never got produced,” said his widow Nina Ginsberg, a painter whom Ginsberg married in 1983. “We moved at one point to California, but, of course, he was too unusual for LA.”

Although “Coming Apart” and “The Werewolf of Washington” remained his only features for many years, Ginsberg worked steadily as a picture editor, especially on documentaries. Among many other projects, Ginsberg edited “Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones” (1990), a portrait of model Christy Turlington, “Catwalk” (1995), and five documentaries for director Lee Grant, including “Down and Out in America” (1986) and “Sidney Poitier: One Bright Light” (2000).

“It came so naturally — he was so happy when he was editing,” Nina Ginsberg said. “He was just in his element.”

After becoming reacquainted with Ginsberg, McBride hired him to edit his made-for-television films “Pronto” (1997) and “Meat Loaf: To Hell and Back” (2000). “Milton was a brilliant editor and fun to be locked up in a room with for a couple of months,” McBride said.

Said Nina Ginsberg: “His thing was to work long enough, make the money editing, and then take time off to do the writing.”

In fact, in the last decades of his life, Ginsberg resumed his work as a director, making a series of innovative self-produced films, including “The Mirror of Noir,” a rigorous examination of the development of film noir; and “Kron: Along the Avenue of Time,” a contemplative study of the concept of time.

“Long after he couldn’t find financing, he persisted in making his own films, at home, on his computer, with found footage and stuff he shot with his phone,” McBride said. “And they were clever and touching. So I was jealous of him for that, too.”

Ginsberg, who received a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the mid-1970s, never let go of his creative spirit. Kino Lorber will soon release newly restored versions of his classic films, “Coming Apart” and “The Werewolf of Washington.”

“He always had a project going,” Nina Ginsberg said. “The saddest thing for me was he just bought a new camera. He wanted to make one more film in his life. As one friend of his said, ‘If I know Milton, he probably had another film after that film.’”

In addition to Nina Ginsberg, the filmmaker is survived by his brother, picture editor Arthur Ginsberg.