by Fred Eldridge

I was born in 1955 so, like many other Americans, television became a constant in my childhood. You’d think that as a result I would immediately be drawn to the medium. But I had no intention of entering the industry until college, when a friend raved about what fun he had taking Television and Radio Production. I took the class and was hooked! I changed my major to communications at the University of Colorado and joined the staff of CUTV, the on-campus production and post-production facility.

In spite of the incredibly low pay, that may have been the best two-year job I’ve ever had. I worked as a studio cameraman, but often went on remotes to shoot plays, lectures, soccer games or whatever needed to be covered. It was here that I learned how to set up and balance cameras, which would be the foundation I needed to be a colorist. I did some Freelance Cameraman work on the side of my full-time job, and managed to make enough money to make ends meet.

Eventually, the pay ran out, so I moved to Los Angeles and found work at a post facility called Editel. In 1981, I was able to join IATSE Local 695 as a tape operator; later, that jurisdiction transferred into Local 700. That turned out to be my foot in the door. After a year of graveyard work dubbing commercials and reruns of Celebrity Tattle Tales and other mind-numbing duties, I got a break and was made a telecine assistant.

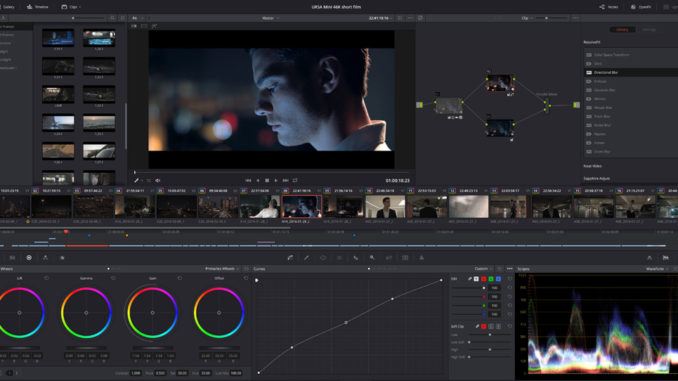

I spent my free time learning to use the equipment required to perform the work of the colorist: transferring film to tape. I was fortunate enough to work with an excellent colorist, Steve Bowen, who taught me a lot about color grading. We would put film up on a Rank Cintel Telecine (that converted the film image to an electronic one), which we would then color grade with a Dubner Color Corrector. By today’s standards, it was like trying to light a fire with flint and steel. We could only alter the three primary and seven secondary colors. I could also manipulate the size and position of the image, but there were no power windows, defocus or kilovectors for isolating specific colors.

After months of training and performing fairly simple film transfers––including the work picture for the Cheers pilot––I had the opportunity to color a foreign acquisition feature for Columbia Pictures. They liked my work, and soon I took over feature mastering for RCA/Columbia Home Video. For the next five years, I colored hundreds of titles, and worked with some great personalities along the way.

I believe that good colorists have the ability to put producers, directors, and DPs at ease. If you know what you’re doing, have a good eye for color and are adept at reading a DP’s lighting, you find you have the ability to see what they were trying to do “overall.”

Acclaimed director/writer Richard Brooks attended color sessions, because much of the work was a pan-and-scan of film that he had shot anamorphically. This required changing the composition of the frame, of which the director wanted complete control. Taylor Hackford attended the color session for White Knights because he had a very specific color scheme in mind. And Paul Mazursky came in to review the final color on a film because his DP was unavailable. These were fairly typical scenarios for feature transfers for home video at the time.

I occasionally worked on television shows, which I liked because the lighting was more suitable for the small screen as opposed to theatrical projection. A projector could throw more light through the image than I could, and the film stocks used then didn’t have the latitude that they do now. The line between lighting for TV and features has since become more blurred. The new digital cameras and film stocks allow DPs more freedom in the way they light.

I could match color on multiple cameras during dailies transfer so that there was little or no color correction needed after the show had been assembled. That got me more TV shows and––I’m not gonna lie––the TV schedule (Christmas break and slow summers) really agreed with me too!

I had the good fortune to work on the ER pilot and spent the next 15 years doing all but three episodes of the series, a once-in-a-career experience. And I worked on almost every pilot and series produced by John Wells Productions during that time.

I believe that good colorists have the ability to put producers, directors, and DPs at ease. If you know what you’re doing, have a good eye for color and are adept at reading a DP’s lighting, you find you have the ability to see what they were trying to do “overall.” This enables you to roll into a scene without a lot of guesswork. I’ve found that if people let me help, I can. A sense of humor doesn’t hurt either.

Even though I grew up on black-and-white television, color became my way of life. I think that coloring is much like editing in that you can teach people the fundamentals, but they either have a talent for it or they don’t. My career has been long and varied and I’ve certainly had my ups and downs. But it’s been fun and, what the hell, I’m still watching TV!