by Selise Eiseman

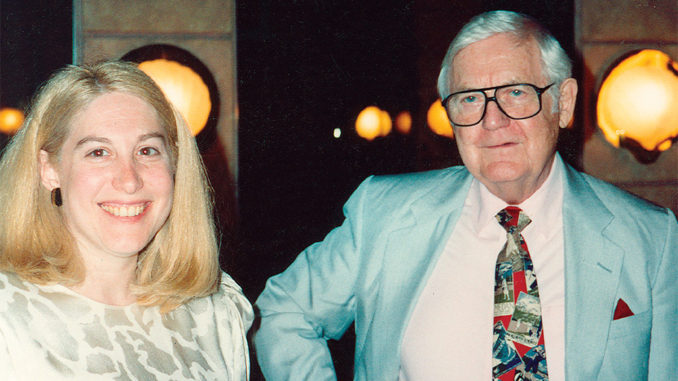

Robert Wise was always a hard worker–whether he was lugging film cans across the RKO lot, syncing up reels of sound, looking through the trim bins for that one particular shot to make a scene play, getting the best performance from an actor, staying on budget, or any of the myriad other jobs and positions he filled in his 72 years in the industry. I got to know Bob late in his life when he was making fewer films but always hoping to direct that 40th one (which he finally did in 2000 with A Storm in Summer). Back in the late 1970s, Bob endowed the Directors Guild of America (DGA) with the money to start a Special Projects department, which was a dream of fellow director and guild national board member Elia Kazan. Bob was the chairman of the Special Projects committee and worked equally as hard to share educational and cultural activities with DGA members, the academic community and the industry public. I worked with him closely, as I headed that department through most of the 1990s. He never said no to a request, even when he was too busy, but rolled up his sleeves and got to work. I imagine that he was like that when he started out in the business in 1933, carrying those film cans for RKO.

Flashback

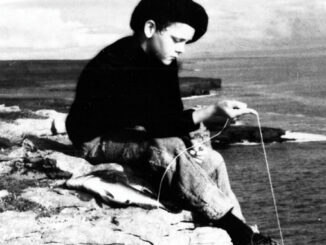

Growing up in Connersville, Indiana, Bob could never get enough of movies; he sometimes saw four a week. Films entertained him and transported him to far away lands and circumstances. As a big fan of Doug Fairbanks, Sr., he went to see one of Fairbanks’ films one day and simply forgot about the time. About half way through a repeat showing, he felt a heavy hand on his shoulder. It was his older brother David, who was sent to bring him home.

It was David who also brought him to his new home in Hollywood when their father lost his business after Bob’s first year at college. David, an accountant at RKO, got Bob a job at the studio, lugging cans of films for $25 a week. From the cutting room to the shipping room to the projection booth, Bob got his first behind-the-scenes taste of filmmaking.

Segue

During this time, he befriended the head sound effects editor, T. K. Wood, who let Bob observe him work syncing sound on Fred Astaire films. Fascinated by this work, Bob was made an apprentice to Wood on Of Human Bondage (1934). Wood soon promoted him to sound effects editor on The Gay Divorcee (1934), The Informer (1934) and Top Hat (1935), and music editor on Alice Adams (1936), although he was not credited on any of them. Bob worked hard and learned quickly. At a tribute to Fred Astaire at USC in 1985, Bob recalled that it was a wonderful period of his life because he had such respect for Astaire in particular, as well as for the very special quality of those Astaire and Ginger Rogers films.

Wood taught him a very useful piece of advice that influenced his later work as a director: “Raw film is the cheapest component of a motion picture.” During that time, Wood suggested they tinker with some film cans they discovered in the vault from Ernest B. Schoedsack’s (co-director and producer of King Kong, 1933) trip to the South Pacific. This became a ten-minute short, A Trip Through Fijiland. RKO showed its gratitude with a $500 bonus for each of them, and Bob received his first screen credit, for the story, in 1935. Bob watched film editors at work as if they were makers of magic. He said that since he never had any place to go, he would spend all his time in the cutting room. But after four years of serving as a sound assistant, he persistently asked to move to the picture side.

First Cut

Bob was always curious to learn even more and observed the work of film editor Billy Hamilton, whose rule was, “Always make the scene play when you’re cutting it, even if it isn’t exactly what the director had in mind when he shot it,” Bob recalled.

Hamilton taught him and took an interest in pushing him ahead as fast as he could learn. Bob was soon doing the first cuts, and Hamilton insisted that he be given coediting credit on such 1939 releases as 5th Ave. Girl and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. After what amounted to a six year apprenticeship in post-production, Bob finally edited his first film, Bachelor Mother, also in 1939.

Mise-en-Scene

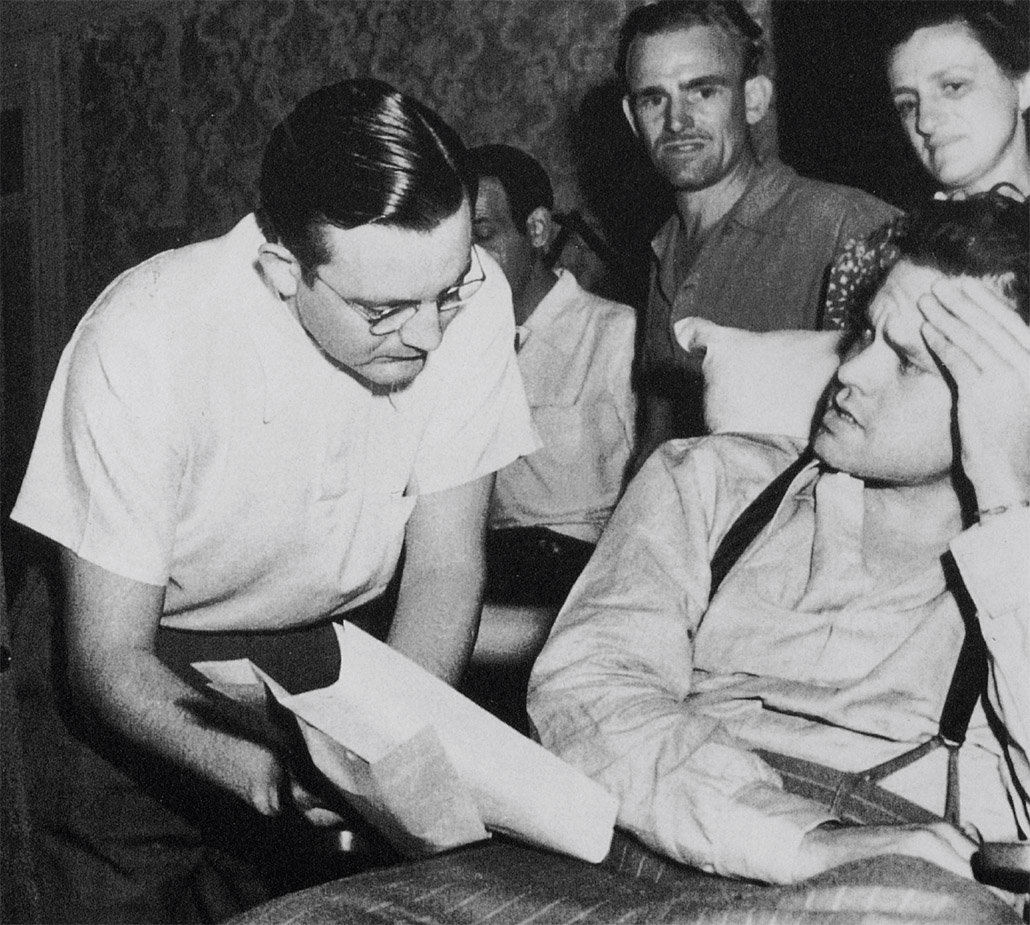

Late in 1940, at the age of 26, Bob got the job of editing the first feature of radio and television legend Orson Welles. Citizen Kane would turn out to be the editing assignment of a lifetime.

In the foreword to Fiftieth Anniversary Album of Citizen Kane by Harlan Lebo, Bob told his side of the story: “In August 1940, I had just finished editing My Favorite Wife when I got a call from my boss, Jimmy Wilkinson, head of the film editing department at RKO. `You know, this Orson Welles–he’s making what he calls tests for his new picture, Citizen Kane,’ Jimmy said. `The studio has finally realized that he’s actually filming footage for the film itself.so they gave him the go-ahead to make the picture. Another editor has been working on the tests,’ he continued. `But now that the motion picture is actually in production, Welles would like somebody else. You’re available, and you’re about Welles’ age, so why don’t you go and talk with him about editing his film?'”

As Orson shot, Bob edited the film along the way, he recalled. They collaborated in much the same way that Bob worked with other directors at the time. “Each day we would review the rushes together; Orson would then describe what he wanted to accomplish with a particular segment, and I would take notes and go back into the editing room to cut the scene,” Bob said. “I worked with my assistant, Mark Robson, to assemble the footage, and then Orson would review what we had done. While he had a good idea of what he wanted from Mark and me, Orson never hung around the cutting room to watch us work or direct the editing.”

In discussing the film’s opening newsreel sequence in Raymond Fielding’s 1957 article in Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television, Bob said he “used 127 pictorial shots cut at a speed to match the swiftly paced, rhetorical commentary, titles of white letters on black background to augment the narration, a profuse number of wipes which gave a definite rhythm to the progress of the film, a montage of official looking newspapers and headlines that further emphasized the feeling that Kane had been an actual person, and iris effects–little used since the days of silent films–to stress specific portions of individual shots.” Bob commented to Fielding that he even went so far as to drag the original film over the cement floors in the editing area to add scratches to period scenes, which were to appear to have been taken from well-used archives.

The classic text on film editing, Karel Reisz’s The Technique of Film Editing, devotes eight pages of description and critique of Kane‘s breakfast table sequence about “whips” and “flash-pans,” and getting the rhythm just right. At a screening for the 50th Anniversary of Citizen Kane held at the DGA in 1991, Bob was queried about his relationship with Welles and said, “I do feel that I learned something from Orson in the manner of pace, energy and dynamics in film. I think he was a master at it.” About his contribution to the film Bob claimed, “Most of the visual look was conceived by Orson and [cinematographer] Gregg Toland. I put that together; strung it together and worked it out in terms of the timing and the pacing of the film. My association with Orson was very close.” Bob was nominated for his first Academy Award for film editing on Citizen Kane.

Rough Cut

Bob’s relationship with Welles continued with the director’s next film, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). When Welles went to Brazil as part of the Good Neighbor policy, Bob met him in Miami and showed him his edits. However, when communication ceased, Bob had the task of recutting the film after a disastrous preview at the studio’s request. He did what he was asked, taking Welles’ wrath for destroying his masterpiece. Bob was caught in the middle between the filmmaker and the front office over Ambersons. “This happens very many times with an editor,” Bob commented. “If there’s a difference of opinion between the director or producer and the front office, the editor is going to find himself on the spot.”

Bob claimed that he learned a sense of structure from working with Welles and Garson Kanin, adding, “It’s not unduly common that editors move on to directing, but very often there’s an editor who’s meant to move up. I think it’s a fairly natural step because you’ve already been exposed to so many facets and elements of film.”

Director’s Cut

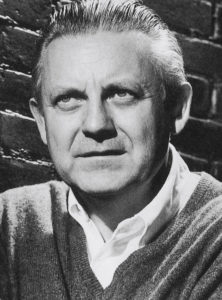

In 1943, Bob got the chance to direct after he asked to direct one of the small “B” pictures. He was editing The Curse of the Cat People (1944) when executive producer Sid Rogell called him to lunch on a Saturday across the street from RKO. When asked to replace the director who was behind schedule and had used up the entire $200,000 budget halfway through an 18-day schedule, Bob initially hesitated. Then he was told that if he didn’t take the job now, someone else would on Monday morning. Bob called it “jumping in the pool and told to sink or swim.” He had ten days to finish the film and as a result of its box office success, was signed as a contract director at RKO until the fall of 1948.

By making the transition from editing to directing, Bob learned that working with live actors on the set was completely different from handling their filmed performances on the Moviola. He quickly learned that it was not necessary to give them too many specific directions and compared the director’s role to that of a critic, saying, “You’re sitting and judging as an audience, responding to what the actors are giving. You think about how you’re going to stage it—but also how it will be enhanced in postproduction.”

The main distinguishing trait of Bob’s style as a director is his extraordinarily lucid sense of rhythm–an outgrowth, no doubt, of his many years as an editor. The arrangement of shots within scenes and the strict correspondence between sequences are of such symmetry and purpose that his films are veritable textbooks on the possibilities of film editing.

In an interview in Harper’s Bazaar in 1971, Bob told Natalie Gittelson, “You can take the boy out of the cutting room, but you can’t take the cutting room out of the boy.” He also told her, “When you grow up in cutting rooms, you know the importance of the last little trims.” She then asked him what it is that makes masterpieces? “The pace of the scenes, the accent of the scenes, the flow of the story.movement, tempo, hitting points,” he responded. “You’ve got to keep the forward movement going.” Gittelson commented that Bob “uses the craft at his fingertips, but an artist’s intuition moves his hands.”

Optical Effects

Bob frequently worked with producer Val Lewton’s unit at RKO, which was affectionately referred to as “The Snake Pit.” They turned out inexpensive, but unusually sophisticated thriller and horror films. He directed Mademoiselle Fifi (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1945), and continued to direct for other producers in different units at RKO, helming A Game of Death (1945), Criminal Court (1946), Born To Kill (1947), and Mystery in Mexico (1948). Bob directed his first “A” picture, the western Blood on the Moon in 1948. Production chief Dore Schary stood behind him as the production budget increased and the studio thought about replacing him for a name director. Finally, in 1949, Bob directed The Set-Up, which closed the decade and his long tenure with RKO. He had become increasingly sophisticated in manipulating an audience’s emotions so “they could never escape.” Bob did this by using all the editing techniques and advice that he learned from his mentors. The Set-Up was a bold experiment with screen narrative—72 minutes in real time in the life of a fading boxer. Bob was dissatisfied with the way that editor Roland Gross cut the fight scenes, so he came into the editing room and re-edited it himself.

Montage

Bob Wise was part of the last generation of directors trained under the studio system and he directed almost every film genre except animation. Many critics discuss his protean quality and versatility. Bob was always trying to expand his horizons and, in the 1950s, directed 18 films that explored many themes and sharpened and perfected his filmmaking techniques.

With the success of I Want to Live! (1958), he was allowed to become a producer-director and was no longer tied to a long-term contract with the studio. He continued to work as hard as he could and to participate in all aspects of his productions.

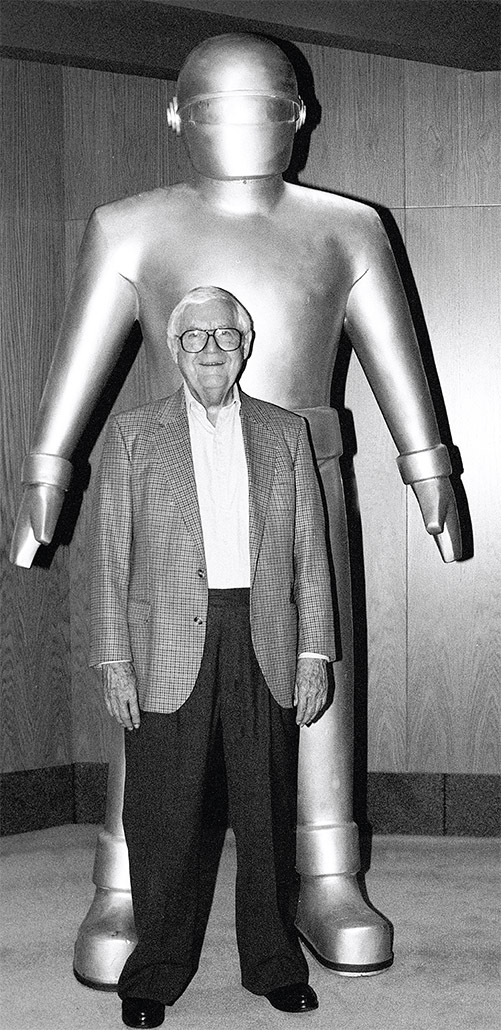

In the 1960s, Bob produced and directed four spectacular road show features—West Side Story (1961), The Sound of Music (1965), The Sand Pebbles (1966) and Star! (1968). In the 1970s, he both produced and directed several large as well as small films—The Andromeda Strain (1971), The Hindenburg (1975) and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) representing the former, and Two People (1973) and Audrey Rose (1977) the latter.

Bob was a film storyteller who was able to translate into cinematic terms the stories of others and reflect on the human condition. In Sergio Leemann’s 1995 book, Robert Wise on His Films: From the Editing Room to the Director’s Chair, Bob stated, “Even though I don’t make so-called personal films, they are personal to me in what they express about matters I feel very strongly about–such as social justice, equality and the need for tolerance. I’m not a man who has just one theme to express through his art. I have different interests and I like to try different things.

“My first reaction when reading a piece of material is if it grabs me as a reader,” he continued. “The second thought is if there’s an audience for it. The third is what is the theme, or the by-product, as I always call it. I hesitate to use the word message because that sounds like a soapbox. I feel that whatever the filmmaker has to say in a film should come out strictly in terms of the story itself and the characters. I’m very careful not to do scripts which talk about what the message is.”

Robert Wise never said no to a request, even when he was too busy, but rolled up his sleeves and got to work.

Bob always stressed that one needed to learn one’s craft, and know the three Ps: Patience, Persistence, and Perseverance. “The lessons I learned as a kid at RKO were–and still are–invaluable; that apprenticeship prepared me,” he said. “There’s no way I could handle this without that training, and of course, that training took time.”

Flash Forward

The last time I saw Bob, he was eating lunch at one of his favorite hangouts, Islands on Beverly Drive, across the street from his office in Beverly Hills. I had a chance to reminisce with him about the past and was delighted that I had the chance to share over 20 years working for this man who still remembered his humble beginnings and always made everyone feel at ease.

I had taught a summer school class on his films, helped with the publication of Leemann’s book on him and watched as he was honored by many times by the DGA, the American Film Institute, the American Cinematheque, and, of course, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In fact, the night the academy celebrated The Sound of Music on February 3, 2003—with six of the children who portrayed the Von Trapp children present and now grown up—was a very special night. I would never pass up an evening with Bob Wise and will always cherish his insights on filmmaking and the sheer humanity in his films—films that he shared with us all. We will miss you, Bob!

Selise Eiseman is a film professor, screenwriter and former Executive Officer of Women in Film. She worked with Robert Wise as the National Special Projects Officer at the Directors Guild from 1990 to 1997 and taught the class “The Films of Robert Wise” at Loyola Marymount University in 1994.