by Kevin Lewis

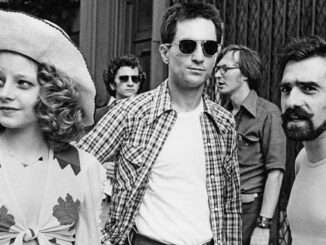

Sixty years after its premiere in June 1954 in Japan, of all places (New York and Los Angeles followed in July), On the Waterfront is still regarded as a seminal film because of its immense influence on acting. In fact, director Elia Kazan created an American acting style in both theatre and film based on the Method Acting pioneered by Constantin Stanislavski. Kazan was a primary influence on director Martin Scorsese. Marlon Brando — in both On the Waterfront and the earlier A Streetcar Named Desire (stage, 1947; film 1951) — was a touchstone for generations of stars from the late 1940s to the present day. To name a few: James Dean, John Cassavetes, Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel, Paul Newman, Rod Steiger, Johnny Depp, Sean Penn and Al Pacino.

Today, On the Waterfront is most famous for the scene between Marlon Brando as disgraced prizefighter-turned-mob-stooge Terry Malloy and Rod Steiger as his brother and corrupt waterfront official to Johnny Friendly, played by Lee J. Cobb. Brando’s plea — “I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am” — is instantly recognizable as a classic line, one of the most famous in movie history.

The film earned eight well-deserved Oscars: Best Picture, Best Director (Kazan), Best Writing, Story and Screenplay (Budd Schulberg), Best Actor (Brando), Best Supporting Actress (Eva Marie Saint), Best Editing (Gene Milford), Best Cinematography (Boris Kaufman) and Best Black-and-White Art Direction/Set Decoration (Richard Day). Steiger, Cobb and Karl Malden were also nominated as Best Supporting Actors for their unforgettable performances, as was Leonard Bernstein for Best Original Score of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture.

Real-life events created a contemporary aura around On the Waterfront upon its release.

However, the film itself, though beautifully made, is a simplistic melodrama of a tragic theme, especially when compared to the original Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Sun articles from 1948-49 by Malcolm Johnson, and the politics of New York and New Jersey, both of which inspired the screenplay. It was a miracle the film was even produced, considering the tortured history of the film script and the actual waterfront scandal, which may ultimately have been responsible for the film becoming a box-office hit.

Johnson’s articles “Crime and the Waterfront” and his book Crime on the Labor Front (1950) were optioned for the movies by director Robert Siodmak and Joe Curtis (a nephew of Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures) for the Monticello Film Corporation with a script by Schulberg in June 1949. Joseph Ryan, President of the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA), sabotaged the film’s production in 1951, when Schulberg completed the script, by writing to William Randolph Hearst, Jr., alerting him that Schulberg had been named by screenwriter Richard Collins as a Communist before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

When Monticello’s option ran out and the material reverted to Johnson in 1952, Schulberg bought the rights from him and asked Kazan to change his then project to Schulberg’s waterfront corruption script. Kazan agreed, since his previous project with Arthur Miller, called “The Hook,” about the murder of longshoreman organizer Peter Panto in 1939, never saw the light of day. The ILA’s Ryan also sabotaged that project for Columbia’s Cohn, with the help of Roy Brewer, head of the Hollywood branch of the IATSE. Brewer demanded that the mobsters be changed to Communists in the scripts, which Miller refused to do. Ryan’s ploy to deny his mob connection was to denounce dissident longshoremen as Communists.

Ryan’s power with the ILA faded after a longshoremen’s strike, led by Father John M. Corridan, the activist Jesuit priest, in 1951. Though New York and New Jersey politicians and police looked the other way at the murders and corruption, Johnson’s articles embarrassed New York City District Attorney Frank Hogan enough to initiate investigations and ultimately indictments of the ILA, and its president.

The articles had initiated a sham waterfront investigation by New York City Mayor William O’Dwyer in 1950, which enraged Governor Thomas Dewey and District Attorney Hogan. In 1953, the Waterfront Commission was created, which exposed the Gambino and Genovese mob control of the waterfront on both the New York and New Jersey sides of the Hudson River. George Meany of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) expelled Ryan and the ILA in 1953.

Real-life events created a contemporary aura around On the Waterfront upon its release. The script itself is melodramatic and solves all social problems within two hours. Stephen Sondheim was perceptive when he reviewed the film for Films in Review in 1954: “A medley of items from the Warner gangland pictures of the thirties, brought up to date.”

In the film, Malloy’s girlfriend Edie (Saint) — whose brother was killed because he was going to testify against Friendly (the model for Ryan) — and Father Barry persuade Malloy to testify. His brother (Steiger) is killed, and Malloy testifies. The film ends with Malloy being beaten up before the longshoreman, who supported him in his decision. Curiously, Kazan simplified his other Oscar-winning assignment, Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), the same way. The director had said that Darryl F. Zanuck, the producer of Gentleman’s Agreement, believed that all social problems could be solved if the romance was resolved — which is exactly the denouement of On the Waterfront.

On the Waterfront has been associated with the HUAC testimony of both Kazan and Schulberg as friendly witnesses, so the film is viewed by scholars and critics as a metaphor and justification for informing on associates. Kazan and Schulberg named names of former fellow travelers and Communists in 1951 and 1952, but Schulberg, in his introduction to the 2005 book On the Waterfront: The Pulitzer Prize-winning Articles That Inspired the Classic Film and Transformed the New York Harbor by Malcolm Johnson, states, “There was no mention of making a film to justify [Kazan’s] HUAC testimony.” Both Kazan and Schulberg at different times were involved with the waterfront project before their HUAC appearances.

What held up the release until 1954 was the refusal of Fox’s Zanuck and Columbia’s Cohn in the early 1950s to produce the movie. Zanuck wanted no part of the film, even though Kazan was his contract director at Fox. Cohn, as noted earlier, killed both the Miller script and the Monticello production at the demand of Ryan and Brewer. It was British producer Sam Spiegel of Horizon Pictures who eventually produced the project, which was released through Columbia. By that time, the Waterfront Commission had spilled the beans on the mob’s connection to the ILA. The film, which was shot in black-and-white, cost $820,000 with the participation of Hollywood’s hottest star, Brando. Frank Sinatra was originally to be the star and was furious when he was replaced by Brando.

There were more headaches for Columbia and Spiegel. Anthony DiVincenzo, the longshoreman who was the actual whistleblower before the Waterfront Commission, sued and won a settlement from Columbia because he was neither credited with being the real-life model for Malloy, nor compensated. Schulberg not only interviewed him, but took down his testimony at the Waterfront Commission hearing. Siodmak, the director who originally optioned Johnson’s writings, sued Spiegel for copyright infringement and won a reputed $100,000 as a settlement. Interestingly, Father Corridan, the real-life model for Father Barry, became a close friend of Schulberg, who wrote the foreword to Allen Raymond’s biography of Corridan, called Waterfront Priest, in 1955.

On the Waterfront is significant because it was the first New York-based movie (the whole movie was shot in Hoboken, New Jersey) to win the Academy Award for Best Film Editing. Milford, who had previously won his first Oscar for co-editing Lost Horizon (1937) with Gene Havlick at Columbia, moved to New York after World War II to pursue his career.

Kazan wanted a gritty, Italian Neorealist look to the film, which was realized by the editing and cinematography. After years of creating seamless, Hollywood editing, Milford adapted perfectly to the documentary-style editing, which added realism to the Method acting. His editing captures the action but does not interrupt the acting. The scene where Malloy walks with Edie along the slummy neighborhood and takes her glove — which he plays with while talking to her — is not interrupted by inter-cutting. It is often cited in acting classes as one of the most inventive improvisational sequences in film, and Milford had the dramatic and emotional sense not to interfere with the playfulness of the moment.