by Michael Kunkes

Thomas Alva Edison once said that he was always afraid of things that worked for the first time. He must have been taken aback in 1877 when his first working prototype of the Phonograph, well, worked. In 1893, Edison’s chief technician, William K. Laurie Dickson, devised the Kinetoscope–an instrument that would do for the eye what the Phonograph did for the ear–which soon came to be known as moving pictures. That same year, Edison created the Kinetophone, his first attempt to combine sound and picture, with simultaneous recording and reproduction of sound. It was decidedly not a success the first time, and kept the legendary inventor out of the sound picture business for 20 years. But the Kinetophone was the ancestor of a steady line of emerging technologies-film, recording, reproduction and amplification-that through trial and error would converge to create the technology of optical, monaural sound.

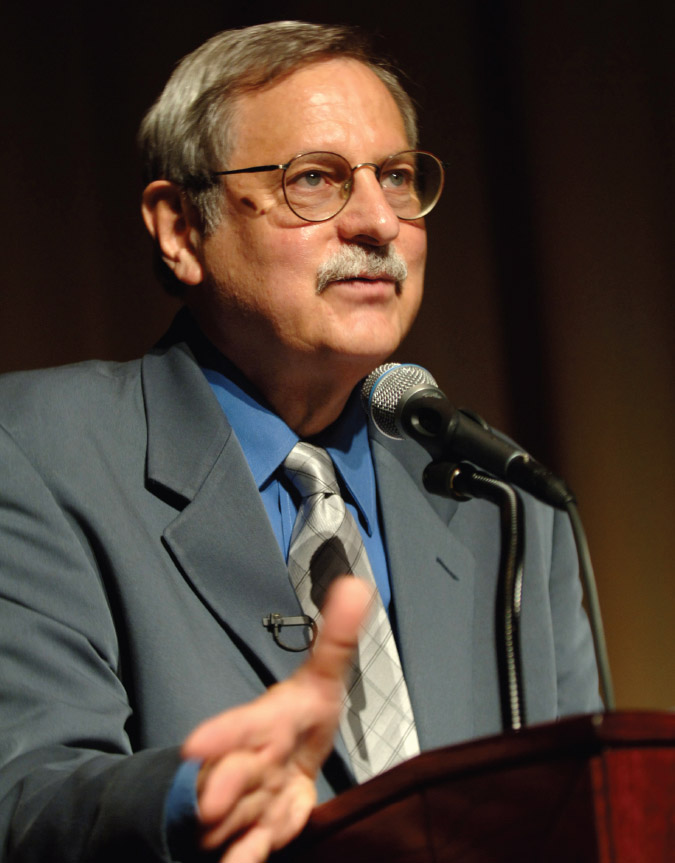

This fall, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) celebrated that convergence at the academy’s Linwood Dunn Theatre in Hollywood with “A Century of Sound,” a threehour program presented by AMPAS’ two-year-old Science and Technology Council. Hosted by Robert Heiber of Chace Productions and presented by UCLA’s Film and Television Archive preservation officer Robert Gitt, the program considered the beginning of film sound from the late 1890s up to the mid-20th century. According to Gitt, a lot has changed since the program was first presented in 1993 by the AMIA (Association of Moving Image Archivists). “At that time, the last word in sound was two-track optical matrix Dolby stereo, and I can’t get over the change in just a dozen years,” he said. To emphasize the academy’s preservation mission, all film clips were experienced exactly as originally seen–with pops, crackles, scratches, noise, splices and hiss all intact–and without digital restoration or clean-up. “It was important that the audience experience the sound as it was,” Gitt added. “We in the Science and Technology Council think that it’s important to remind everyone of how we got to where we are today and how the lessons of the past will hopefully point to the future.”

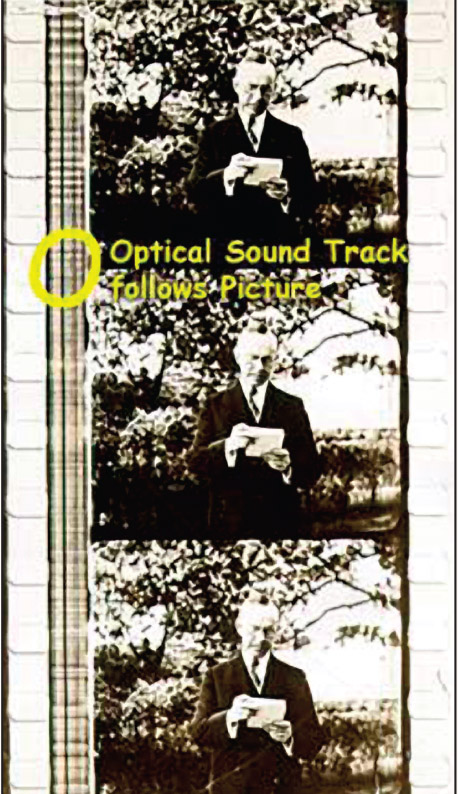

One of the biggest treats was seeing the optical tracks alongside the clips. “We printed the clips in a way that departs from the normal way optical tracks are printed,” Gitt explained. “Normally, optical sound is printed 20 frames before the picture to compensate for the fact that picture goes through the projector gate intermittently, but sound is picked up continuously. Any sound projected on the screen along with the picture would then be out of sync with the actors.” To compensate, Gitt had all the analogue optical tracks re-recorded to magnetic sound, without going through multiple photographic generations or electronic copying. “I wanted people to be able to see the actors but also to simultaneously see the modulation, he added.

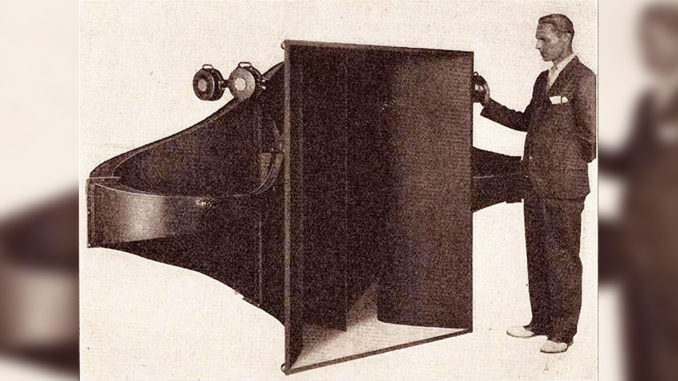

Though the program focused largely on American developments, Europeans played a large role in sound’s early history. France’s Leon Gaumont introduced the Chronophone in 1902, which used large boards to reflect and reinforce the sound being recorded by the huge phonograph horns. He also developed a compressed air device, called the Elgephone (after his initials) for reproduction and amplification. And in 1903, German Oscar Messter used electrical circuits to lock the camera, phonograph and projector motors together to create an excellent synchronization system.

Back in America, things were getting less scientific and more silly as future Paramount founder Adolph Zukor introduced Humanovo (similar to Actologue and Ta-Mo-Pic), in which troupes of live actors stood behind the screen and actually mouthed the words of the onscreen performers.

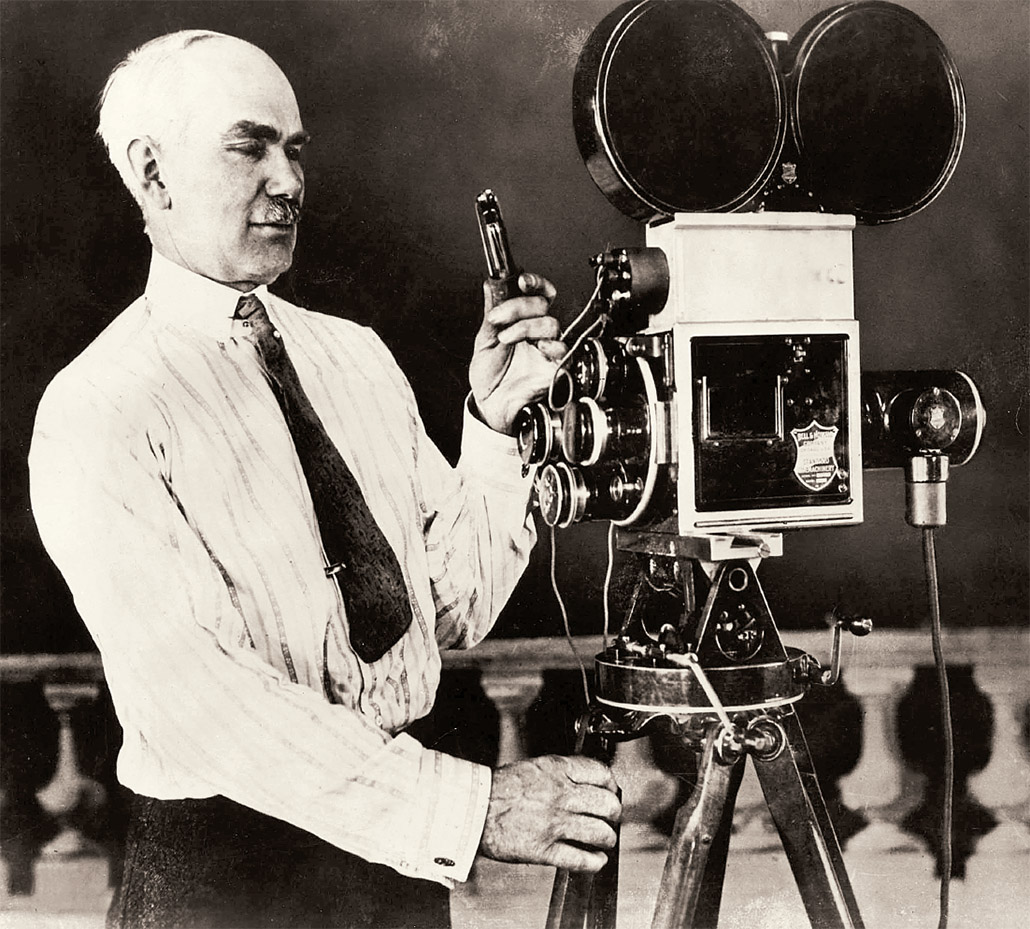

In 1913, Edison returned to his ill-fated Kinetophone. A crude recording horn allowed the phonograph to be placed outside of camera range so that both sound and picture could be simultaneously recorded, with sound grooved onto huge 78 rpm discs that could last for six minutes of running time. Playback was achieved by a series of pulleys and a long belt that linked the onstage phonograph with the projection booth. The Kinetophone actually was briefly in vogue during 1913-14–until a fire in the Edison lab destroyed the equipment, along with Edison’s sound aspirations. The Kinetophone was the culmination of a long line of early sound-on-disc experiments that included Vivaphone, Electrograph, Phoneidograph and Cameraphone.

Sound-On-Disc

The next breakthroughs began at Bell Laboratories, which in 1913 purchased the rights to the audion tube, invented by Lee de Forest in 1906. The audion made it possible for the first time to amplify weak electrical signals and marked the beginning of the electronic era. Bell engineers improved the vacuum seal on the audion and invented high-quality condenser microphones, as well as loudspeaker telephone horns that were used for the first time at the 1920 Republican convention. The company also forever replaced the recording horn by devising an electrical cutting head that used a stylus, which vibrated in an electrical field in response to the amplified signals from the microphone.

At that point, Bell and its Western Electric subsidiary, led by Stanley Watkins, married the electronic cutting stylus to a special, constant-speed motor attached to a movie camera that drove both the turntable and projector to ensure perfect sync. Despite banks of tubes, storage batteries and numerous attenuators, a grand total of eight watts of sound were generated, and frequency response was limited to 4300 cycles. But the sync was perfect, the sound could be amplified to fill a large auditorium and up to 1,000 pressings could be stamped off each original master wax disc.

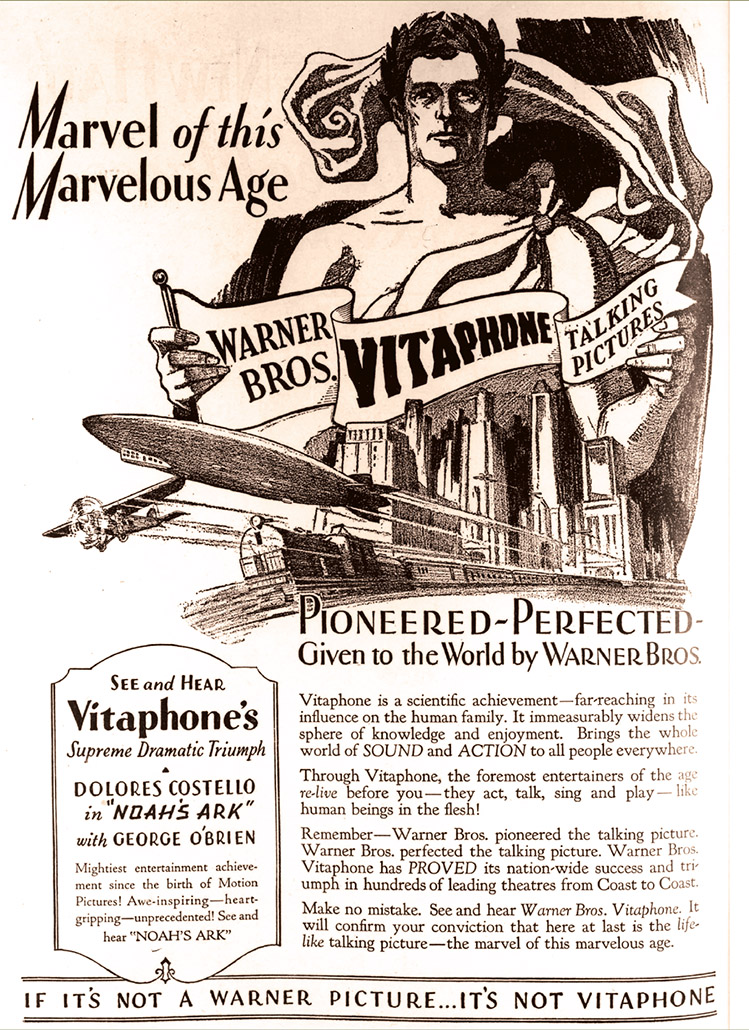

The only problem was that Hollywood studios and exhibitors by this time had become somewhat resistant to sound, partially due to the costs of retooling, and partly because of what at the time were legitimate concerns over losing vast audiences for the universal language of silent film. For better or for worse, no one was interested in the new system, which was christened Vitaphone. Until, of course, Warner Bros. entered the picture.

The story of Vitaphone is well known today. Samuel L. Warner championed the process, struck a deal, and in the fall of 1925 moved a crew into the old Vitagraph Studios in Brooklyn to produce Vitaphone shorts, while Watkins set about wiring Warner theatres for sound. Two dates in movie history are inexorably linked to the Vitaphone. On August 6, 1926, Don Juan, starring John Barrymore and Mary Astor, opened with a synchronized orchestral accompaniment, and on October 6, 1927, The Jazz Singer opened in New York. Warner, however, worked himself to death and passed away the day before the latter opening, but he set the industry on a path from which there was no turning back.

1923. Courtesy of AMPAS

Sound-on-Film

The development of sound on film literally mirrored the timeline of sound on disc, except that sync and amplification were less an issue than portability and sound quality. Simply put, optical sound was photographed, not phonographed, by varying the light going through the film according to the signal coming from the microphone.

Over time, two ways were created to modulate that light. One was the Variable Area Track, in which the overall brightness of the light went from stark white to pure black, with a shutter changing the width of the light beam being photographed onto the film. The other was the Variable Density Track, which maintained the same beam width but instead created a series of various shades of gray from black to clear and back again.

Optical sound’s roots go back to the 1884 experiments by Alexander Graham Bell and Sumner Tainter, which used a beam of light modulated by a jet of black ink coming from a nozzle attached to a sounding board to create the first spiral (as opposed to Edison cylinder) recordings. By 1910, Eugene Lauste, a French engineer and onetime Edison employee, succeeded in photographing and reproducing sound on film, using both Variable Area and Variable Density Tracks. He developed a telephone-like microphone that generated weak electrical currents, causing a pair of electromagnets and a string galvanometer to vibrate a wire with a small mirror attached. A beam of light bounced off the vibrating mirror to expose a pattern on the film representing the original sound modulation.

Meanwhile, back in the States, de Forest had also turned his attention to film. Supported by two young inventors, Theodore W. Case and Earl I. Sponable, he developed Phonofilm, which used a fluctuating glowlamp called the AEOlight to produce a Variable Density soundtrack. By 1924, Phonofilm had 20 outfits giving roadshows in theaters, featuring stars of the day such as singers Eddie Cantor and Abby Mitchell and comedians Joe Weber and Lew Fields.

The first Variable Area Track system emerged in 1928 as Photophone, a joint venture between General Electric and RCA, resulting from Charles Hoxey’s experiments with vibrating mirrors to record radio broadcasts in 1920. Photophone used the galvanometer, which had a tiny mirror vibrated by fluctuating magnetic currents. As the mirror rocked back and forth, a series of light and dark lines was produced across the entire width of the track.

But it was the Case and Sponable Phonofilm system that gained the honor of being the first theatrically successful sound-on-film system. William Fox formed the Fox/Case Corp. and rolled out the renamed process, Movietone, in January 1927 at New York’s Sam Harris Theatre. Movietone soon proved more durable and portable than Vitaphone, (though at first, neither process freed the motion picture camera from its sound proof booth) and was used to film 1928’s In Old Arizona, the first all-talking sound-on-film picture, and also the first sound picture to be photographed almost entirely outdoors.

Ultimately, however, most studios adopted Western Electric’s Variable Density recording, including MGM, 20th CenturyFox, Paramount, Universal, and Columbia. Warner Bros., RKO Radio Pictures and Republic Pictures used RCA’s Variable Area recording. By the end of 1929, order began to emerge from the chaos, and over 4,000 theatres had been wired for sound by Western Electric’s ERPI (Electrical Research Products, Inc.) and another 1,200 by RCA. Thousands of projectionists had to train to learn motor-driven projectors, optical sound heads, vitaphone turntables, amplifier panels, volume controls, loudspeakers and faders from one projector to another.

With sound now a fixture, the industry could turn to other matters. Old, noisy carbon microphones were eliminated completely, and the early and bulky Western Electric condenser mics with the vacuum tube pre-amps in the base were redesigned and made smaller. More sensitive and dynamic moving coil mics became available, and RCA developed a ribbon velocity microphone that was perfectly suited for music recording.

At theaters, the single-driver horn loudspeaker was replaced by new types of two-way loudspeakers with multi-cellular horns for improved frequency response and more uniform dispersion of highs and lows. ERPI introduced a new wide range sound system, installed by “The Decibel Man,” as the publicity at the time called your friendly ERPI serviceman. And by the 1950s, Altec (the successor to Western Electric) and RCA were bringing out vastly improved loudspeakers, along with higher quality projector sound heads and amplifiers.

As the quality of the films themselves improved, dealing with noise became critical, especially during a film’s quieter moments. Western Electric introduced “noiseless recording,” a way of biasing the light valve to reduce the amount of light being passed though the track during MOS (without sound) moments, thus greatly reducing hiss and allowing dirt, scratches and film grain noise to be edited in the reproduction of Variable Density Tracks.

Science and Technology Council Copyright AMPAS

RCA introduced a mechanical shutter into its sound recording gear that marks off most of the clear area where the Variable Area Track is largely unmodulated. And both systems began to use duplex, or dual bilateral recording, where two tracks are side by side, each a mirror of the other. It proved a good solution, and as late as the 1960s, Warners was still using duplex tracks for its mono releases. By 1950, mono recording and playback had advanced about as far as they could go, with the advent of magnetic recording, stereo and widescreen. Bell Labs had experimented with broadcast stereo in 1933 and Western Electric developed fourtrack stereo in 1940, but those efforts were aimed at phonograph records, not the cinema.

“Compared to current technology, optical sound had a narrow dynamic range, as well as a limited frequency response that ranged from 50 to only 8000 cycles,” Gitt explained. “Still, early sound was very intelligible and often quite pleasant to listen to as the 20th century neared its midpoint.

“But it took thousands of talented and dedicated men and women to bring about the gradual perfection of sound, he acknowledged. “Most of their names, we will never know.”