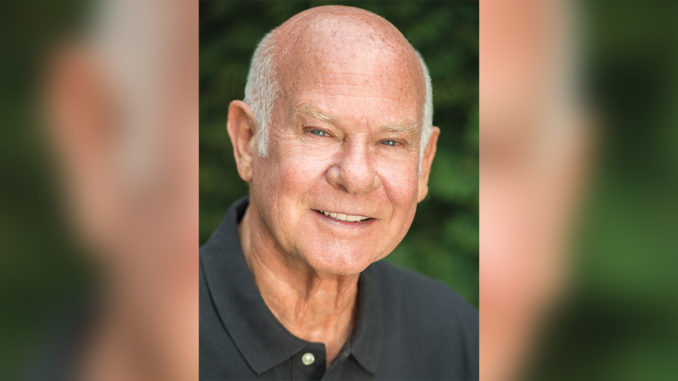

by Mel Lambert • portrait by Wm. Stetz

Helming a re-recording crew during the preparation of an intricate motion picture soundtrack takes a unique combination of technical capabilities, people skills and an appreciation of sound and imagery — plus a healthy sense of humor. For many who know him, Donald O. Mitchell exemplifies all of these qualities and more, and is a worthy recipient of the Editors Guild’s prestigious 2013 Fellowship and Service Award, which will be presented to him at a ceremony scheduled for October 5.

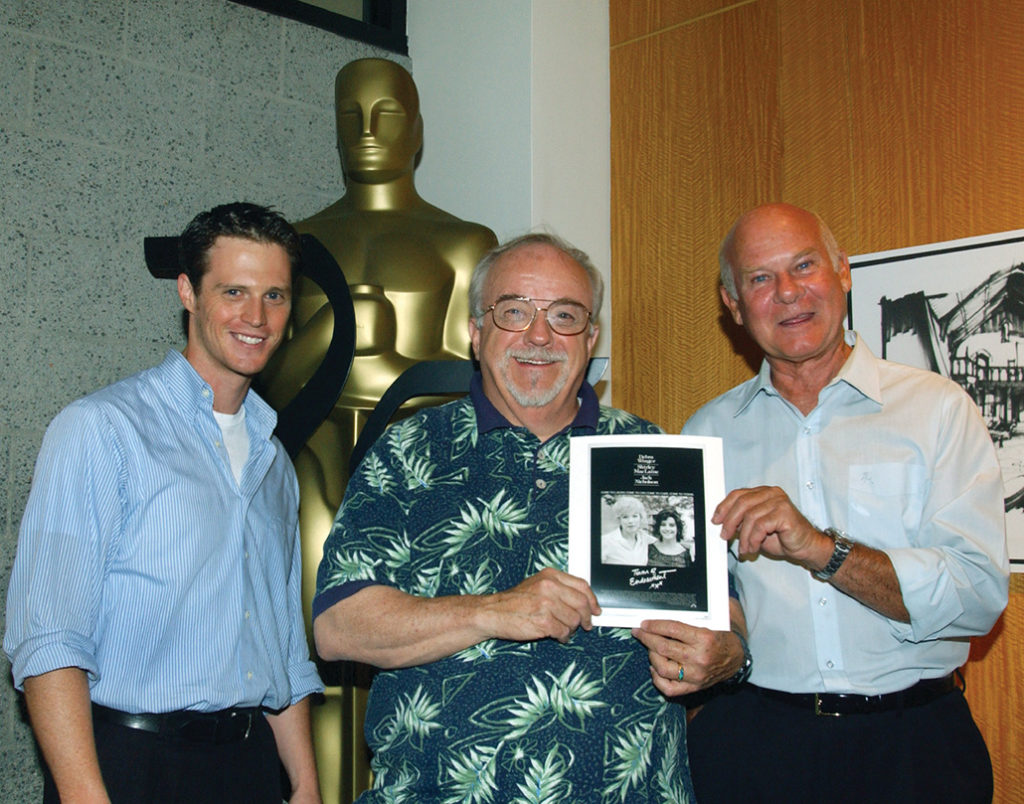

Starting, unusually, as a draftsman at 20th Century-Fox in 1955, Mitchell spent the following four-and-a half decades in the film and TV industry, including many years at Warner Hollywood Studios’ Stage D, as well as a brief sojourn at Warner Burbank Studios. With fellow mixers Gregg Rudloff handling sound effects and Elliot Tyson overseeing music, in 1990 Mitchell won an Academy Award for Best Sound for Edward Zwick’s Glory (1989), and has been nominated for 13 more in the same category: The Paper Chase (1973), Silver Streak (1976), Raging Bull (1980), Terms of Endearment (1983), Silverado (1985), A Chorus Line (1985), Top Gun (1986), Black Rain (1989), Days of Thunder (1990), Under Siege (1992), The Fugitive(1993), Clear and Present Danger (1994) and Batman Forever (1995). Between 1973 and 1998 — the year of his retirement — he worked on nearly 120 films.

Despite a teenage interest and a planned career in architecture, in the mid-1950s, Mitchell joined the Fox studio drafting department before moving to “loading mag dubbers, handling recording duties and then limited engineering — repairing, but not necessarily running a console,” he recalls. “One day my boss came to me and said, ‘You’re mixing dialogue today.’ And that was it — Go! It was a session for one of Aaron Spelling’s shows; we did them all: Charlie’s Angels, The Love Boat and many others. I also probably mixed at least 50 percent of the M*A*S*H TV shows.”

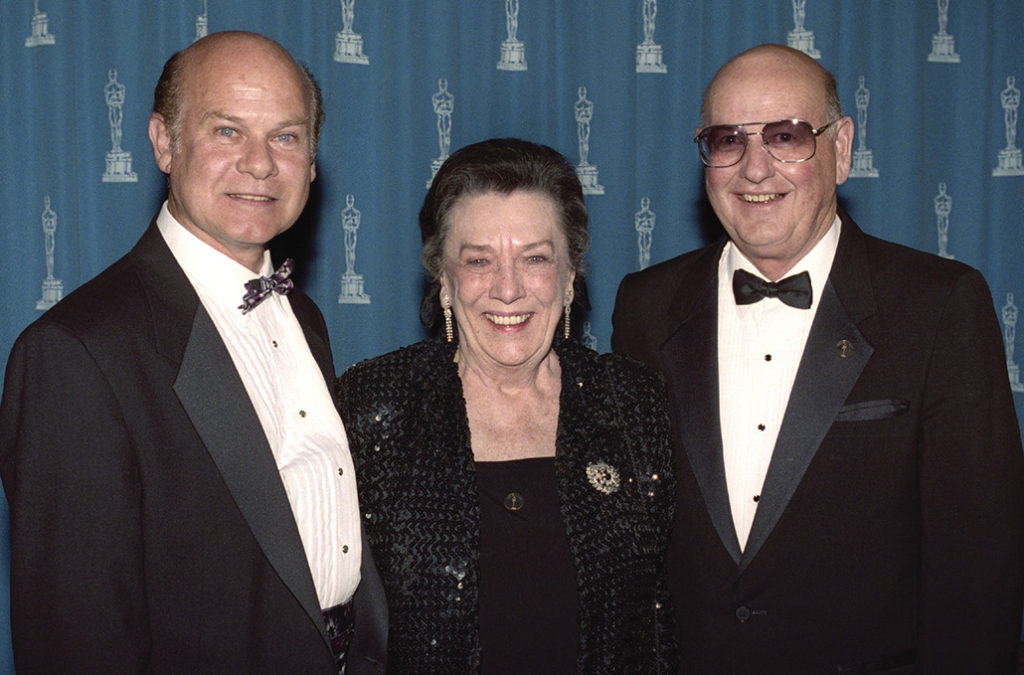

Photo by Long Photography. Courtesy of AMPAS

When Mitchell first went to Fox, the studio was producing landmark films like The Sound of Music (1965), Hello, Dolly! (1969) and other big musicals. “It just blew me away what was happening on their stages,” he says. “How wonderful it all was; I was star-struck from day one. My heroes at that time were Harry Leonard, who worked on The Day The Earth Stood Still [1951], Curly Thirlwell, Douglas Williams and the legendary Murray Spivack, who worked on King Kong [1933], Spartacus [1960], Patton [1970], The Sound of Music and many more. I like to think that I had an ear for sound; I admired the works of the masters.

“In 1973, I did my first film at Fox — The Paper Chase [1973] — handling dialogue re-recording,” he continues. “Director James Bridges was great to work with; it was an enjoyable, fun and interesting project, although something of a white-knuckle ride for my first film!”

Mitchell is diplomatic about his decision in the late 1970s to move from Fox to the Warner Hollywood facility, the former Goldwyn Studios lot on Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood. “To put it nicely,” he states, choosing his words carefully, “Goldwyn was more interested in quality sound work. It was an opportunity for me to work [at a facility] and do better projects.”

Mitchell’s Oscar for Glory came as a surprise. “Personally, I never thought that any project I have worked on was award-worthy, or would go in that direction. It never crossed my mind. The Glory soundtrack with Gregg and Elliot was the very best we could do. Lon Bender was supervising sound editor and sound designer on the film; he did a fabulous job, which made Glory as good as it was. Lon totally made us look good!”

The re-recording mixer considers Raging Bull (1981) with director Martin Scorsese to be his most challenging film, “mainly because of the fight reels and not wanting to have just the regular sound of punches. There had been a lot of fight films and they pretty much all sounded alike; we really didn’t want to go there. Supervising sound editor Frank Warner cut animal sounds for enhanced drama and human effect, which crossed into score. Martin Scorsese was very patient. He knew what he wanted and was willing to wait until you found it.”

In terms of his most enjoyable film project, “Top Gun[1986] with director Tony Scott was a high-energy film that was also a lot of fun — and a great sound job. Also Joel Schumacher, working on both Batman & Robin[1997] and Batman Forever [1995], cracked us up! He was a good, all-around guy, and delightful to work with; very easy-going with a great sense of humor. My other favorite, fun projects were La Bamba [1987], directed by Taylor Hackford — a wonderful man — and The Fugitive, directed by Andrew Davis and co-produced by Peter Macgregor-Scott — both of whom kept us amused on the re-recording stage.”

A cherished memory came during the recording of Jim Carrey as the Riddler’s ADR lines for Batman Forever. “At first, Jim was very reluctant to come in on a Saturday morning, but soon realized that ADR was a creative process,” Mitchell reveals. “The production sound was poor because it had been recorded inside the cavernous Spruce Goose hanger in Long Beach; it was very reverberant with an unpleasant echo, even when the camera moved in for close-ups. Jim did an amazing job of fixing that eight- or nine-minute scene toward the end of the film, because he re-created the entire scene. He pretty much re-voiced the entire reel.”

Courtesy of Greg Russell

At Warner Hollywood, Mitchell worked mainly on Stage D, a large, theatre-sized room with 110 seats in front of the console. “It produced good sound and was very representative of what was out in the field,” he offers. “You could mix a film on that stage, take it to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, for example, and it sounded the same. Stage D was one of the nicest stages in Hollywood. It had one of the first automated Harrison PP1 analogue consoles, later with Neve Flying Faders.”

Mitchell calls technical support at Warner Hollywood “second to none, thanks in no small measure to John Bonner [formerly sound director at Fox Studios and then director of special projects at Warner Hollywood until his death in 1996] — the man — and senior vice president of post-production Don Rogers, who was probably the best man to work for. I pretty much owe my career to Don and John, two of the greatest guys in the world. Curt Behlmer took Don’s job when he moved to Warner Burbank; they were both cut from the same cloth: competent, able men.

“For music and sound effects mixers, I always look for nice people who know what they are doing and don’t walk into the room with their own agendas,” he adds. “After all, mixing a film is a team effort. I like something in between a serious and a humorous working environment on the stage. A little humor is always nice to have around, but we are spending an awful lot of the studio’s money doing some really nice work, so we can’t fool around too much.”

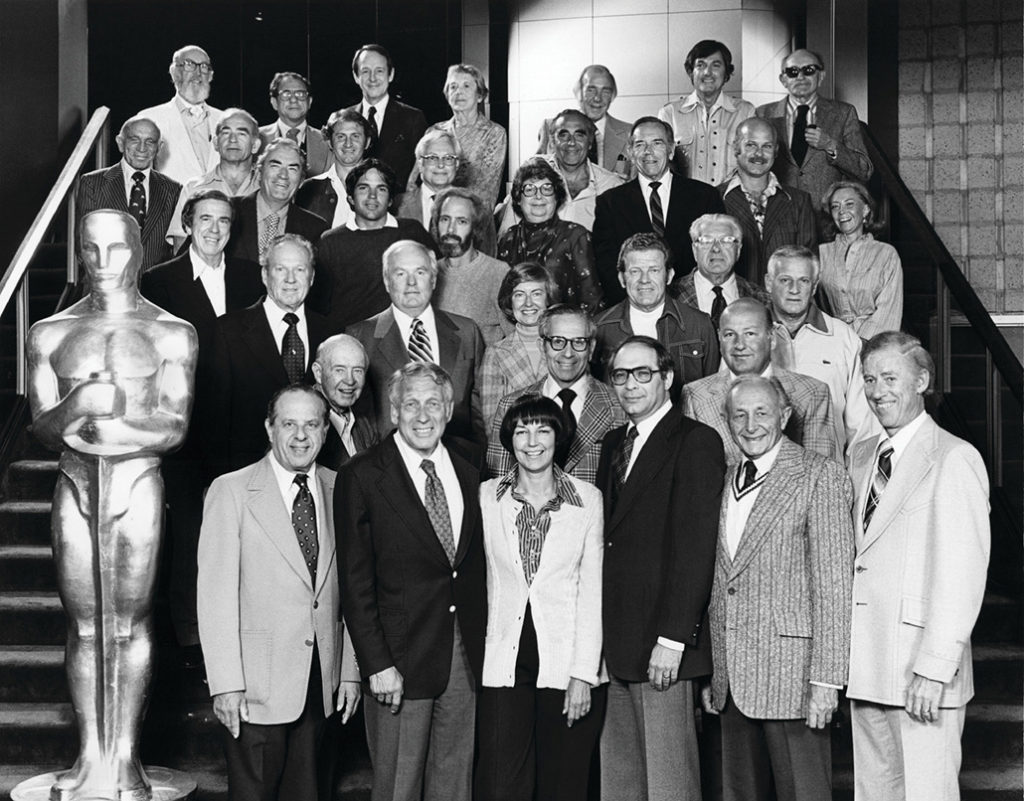

Courtesy of AMPAS

The mixer liked to do his own pre-dubs. “In fact, I don’t know how guys work with somebody else’s pre-dubs,” he confesses. “But these days, they have to because of the prevalence of two-mixer teams and accelerated schedules. Legible cue sheets are always a great help — something that you can see easily in the dark!” The dialogue mixer has worked with a number of successful effects and music mixers, including Frank Montano, Rick Kline, Michael Herbick, Greg Russell, Kevin O’ Connell, Elliot Tyson, Mike Minkler and Gregg Rudloff.

Preparation and flexibility are always the keys to success, according to Mitchell. “We would start pre-dubbing right onto reel one,” he says. “If it was the first day with the director, you might run through the whole thing and get his views about how he wanted his movie to sound; if he was staying around, you didn’t need to do that. You had to be totally flexible; to go where you need to be. Your pre-dubs also had to be flexible so that on the day of finals, the director can have what he wants, and you don’t have to go back and take a pre-dub apart. I liked lots of options — the more the merrier!”

When fader automation came to the mix stage, things began to change, according to Mitchell. “It made pre-dubs a lot easier, because things could just sit on marks and you didn’t have to pay attention to them,” he explains. “In the beginning, before Flying Faders, you’d have pre-dubs all over the place and they had better be pretty good and pretty accurate. We would pull at least a dozen mag dubbers and often bring extra consoles into the room; consoles would be all over the place. We had outboard music consoles all the time, depending upon how deep some of the pre-dubs would be. And you needed pretty good notes so that you knew what was going on.”

Photo by Long Photography. Courtesy of AMPAS

Regarding his mixing philosophy, Mitchell says, “Dialogue is king. Personally, I don’t like dialogue off the walls; I don’t like pretty much anything coming off the walls except subliminal textures and ambiences. As soon as you are aware that the speaker on the wall is working, then I think that’s wrong. Even with a fly-by of a helicopter that goes by the front and then comes off the wall, I’ll sit there and think, ‘Yeah, they put it into the surrounds.’ I don’t know if every audience thinks that way, but I do and it bugs me. It often pulls me out of the movie. A film happens in front of me; music belongs a little bit in the surrounds, with ambience in the surrounds. But that should just be filling up the room; you should not be aware that is happening. If you are aware, then it’s too loud!”

Mitchell moved to the Warner Burbank facility in 1994 “because they opened a new room there [Stage 2, equipped with a Solid State Logic SL-8000 with film-style modifications].” He did one or two films there and then returned to Warner Hollywood, where he saw out his re-recording career. “Coming back to Warner Hollywood was just coming home to what I knew,” he says. “I was just more comfortable on Stage D. At Burbank, I was working on a small dubbing stage. I didn’t want to leave Stage D, which was an immense room. They just needed somebody to come over and open the new room for them.”

As a re-recording mixer, Mitchell was a member of IATSE Local 695, the Sound Technicians local. Less than a year before his retirement in November 1998, he and his fellow post-production mixers in 695 were brought into the Editors Guild, on January 1, 1998.

As many of his friends and colleagues are aware, Mitchell’s greatest love is sailing. In his spare time, he built a 50-foot fiberglass-bodied boat — later christened the Orion — within his backyard in Van Nuys, California, about 20 miles from the Pacific Ocean. “If you are into boating then you dream about boats,” he explains. “It has always been a hobby. Orion was completed toward the end of my time at Warner Hollywood Stage D, and then trucked to the Marina. It took around 20 years to build it. After all, I had a full-time job! I covered it up for around five years because I was too busy with other things. It’s fiberglass because I knew that a wooden boat wouldn’t survive the Valley heat for all those years; it had to be glass or steel.”

An active member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) Sound Branch Executive Committee for a number of years, Mitchell served three terms on its Board of Governors. “I was totally committed to the Academy’s aims and aspirations,” he states. “One term I spent on the Board was with sound editor Kay Rose and, at that time, the Academy was desperately trying to reduce the award ceremony’s airtime, and they were looking seriously at the Sound Branch. Kay and I were responsible for diverting that idea at that time.”

Photo by Greg Harbaugh. Courtesy of AMPAS

According to Mitchell, the Academy wanted to move the Sound Editing and Mixing awards to the separate Scientific and Technical Awards Ceremony — “and give us five seconds of airtime, like they do the SciTech people on the Oscars broadcast,” he continues. “Yet everybody knows that without the sound people, the motion picture industry would not survive. So kudos to Kay for helping avert what I consider would have been a catastrophe of taking the Sound awards off the awards show. It was insane!”

Mitchell is the first to concede that after 45 years, “I don’t really miss the work — it was a great run for me, but it’s done. I still enjoy films [and remains an active member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Sound Branch], but when I hear a mix that I disagree with, then I want to go back to work! But really I’m happy to just watch the movies; I now focus on the end result and not the process.”

For the most part, the mixer feels that post-production hasn’t changed much. “We still try to get a great soundtrack on the screen, and automation helps, of course,” he offers. “We now have two-man crews working with a group of other mixers, which means that they are working with other people’s pre-dubs, which makes it really difficult. And, once in a while, that shows up in the finished product. It’s not as good as it could be. Digital technologies — dubbers and workstations — made our life easier. I liked the enhanced fidelity and not having to worry about generational losses, plus the ability for total reset to reset everything.”

What makes a good mix to Mitchell’s ears? “My criteria of a good mix is that you can hear everything, there are no distractions, and the soundtrack keeps you in the movie. Everything Andy Nelson does is wonderful; everything that Steve Maslow does is wonderful. And Greg Russell is a great music mixer. When I go back and review my soundtracks, I always wonder, ‘What was I thinking?’ And I want to go back and fix them. But maybe everybody feels that way?”

His best advice to a newbie looking to pursue a career as a re-recording mixer? “Have an open mind and be flexible,” Mitchell says. “And show up each day on time. Always speak your truth as you see it. All in all, I was totally happy with what I was doing. I don’t have any regrets, and I don’t think that I really ever did.”

Editor’s note: To read more from Don’s admirers, go here.