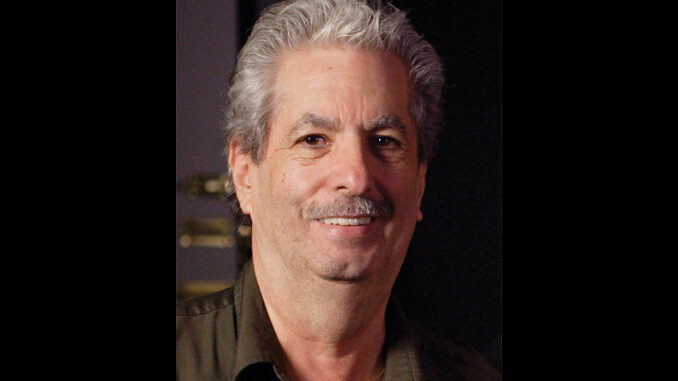

by Marco Zappia

A ”Jack-of-all-trades and master of none” is what I thought of myself until I turned 30. That’s when my wife, Carole Ann, found an ad for an engineering job at CBS. Knowing nothing about the broadcasting industry, I was reluctant, but with the help of my degree from the Western Electronic Institute and some last-minute cram sessions at the library, I was hired as an engineer in the videotape department.

It was 1968; variety shows, game shows and religious shows were shot and edited on two-inch videotape. I was amazed how videotape was edited in those days. They used a Smith Editor consisting of a microscope, a splicing block with a special bar, a sharp razor and a solution loaded with alcohol and powdered iron shavings.

In 1969, I helped install the EECO 900 Editing system––a new and innovative system by which editing could be done between two machines using time code recorded on one of the tracks on the videotape. It was a real breakthrough in videotape editing, and I was assigned to train the editors. They insisted that I assist each of them until they learned the system. Each editor at CBS (some of the top in the business at that time) had their own way of editing, and I learned from each of them.

Because of the quality of two-inch tape, we still made six to eight physical splices for changes that we couldn’t make electronically, in order to keep from dubbing the show down a generation. Three years later, while I was assisting editor Bill Kendall on Hee Haw, he decided to leave the show. I was moved over to the editing chair in 1971 and, after the first year of editing, I won my first Emmy Award. When that show was cancelled, I requested to edit shows that no one else wanted to edit––because I knew those were the shows from which I could learn the most.

I also assisted on the first four-camera sitcom shot on videotape, All in the Family. After the first season, the editor left the show and Bob LaHendro, the AD, wanted me to edit because he knew I could do the job. The director, John Rich, was tough, but working with him did more for my career than anyone else. John taught me how to pick the best performances; he became my mentor and good friend. One day, he asked me to blend the laugh across the edit point that was cut abruptly when we changed performances. In the 1970s and ‘80s, there was only one audio track on videotape, so audio couldn’t be recorded separately and blended.

I came up with the idea to record past the edit point to let the entire laugh go by. When I went back to make the picture edit, I took a CBS label, folded it in half and held it between the tape and the audio erase head. At the exact right time, I quickly pulled the label out and— voilá!––the laugh blended. Whenever you work with talent like John Rich, who push you and your equipment beyond your limits, it drives you to become better at your craft.

In 1978, I went to work for CFI. They were an IATSE signatory and, because of my ten years of experience, I was able to join as an editor. My first experience editing on a nonlinear system was with Rich again on MacGyver, using the Montage III. It allowed random access to all material by utilizing 17 super-beta VCRs with the same material on all 17 beta tapes.

In 1994, I tested the Avid (only a single camera editing system back then), and worked with Avid and my assistant, Jeff Bass, to adapt it to edit multiple cameras. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, I was cutting as many as five different series at one time; three assistants organized all the material and I would go from room to room doing the first and second cuts. When we had minor notes, my assistants––Jeff, Kevin Mullich and Keith Gore––finished the cuts and got the show ready for the online process.

Throughout my career, I worked with some of the best directors, producers and technical artists in the industry: people like John Rich, Norman Lear, Michael Jacobs, Matt Williams and so many more. I started in the industry when they were cutting two-inch videotape with a razor blade––and it’s hard to believe that today you can cut a film at home on a lap-top computer!

I share all these anecdotes and insight in the memoir that I’m currently writing, “The Smartest Guy in the Room.” Forty years, 19 Emmy nominations, and numerous wins later, I’ve learned that a good editor must strike a delicate balance between technical know-how, inventiveness, creative ability and social grace.