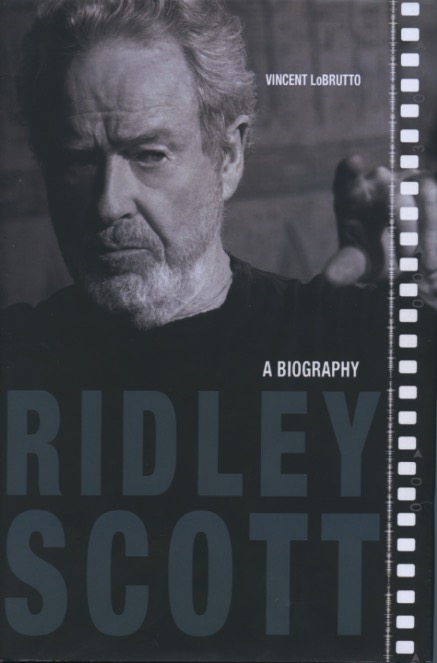

Ridley Scott: A Biography

by Vincent LoBrutto

Screen Classics Series

University Press of Kentucky, 2019

Hardcover 267 pages $40

ISBN # 978-0-8131-7708-3

by Betsy A. McLane

Sir Ridley Scott’s extraordinary career in television and motion pictures is long overdue for a thorough historical and critical examination. Today, with books on almost every imaginable cinematic subject popping up regularly, the lack of definitive writing on Scott seems an odd omission. Vincent LoBrutto’s Ridley Scott: A Biography, takes a step toward addressing this lack, but unfortunately does not fully complete the necessary leap to become the book that will fill the gap.

As part of the University Press of Kentucky’s Screen Classics series (series editor Patrick McGilligan), Ridley Scott: A Biography joins a lineup that includes publications such as Joseph McBride’s essential Hawks on Hawks, Michael Sragow’s winner of the National Award for Arts Writing, Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master, and the more recent Hollywood Divided: The 1950 Screen Directors Guild Meeting and the Impact of the Blacklist (reviewed in CineMontage Q4 2017). The series, with over 50 titles on its list, varies widely in value of subject matter, research quality and insightful writing. LoBrutto’s offering scores high on the first of these, reaches solid ground on the second but disappoints on the last.

The author demonstrates great knowledge of Scott’s entire body of work, and references seemingly every available newspaper article, interview, review, production budget and box office number associated with the filmmaker. The bibliography consists mainly of books, but the wealth of resources consulted and footnoted is much more expansive, and it would’ve been a great service to researchers if these were included. Ridley Scott evidences endless hours of dedicated research and information compilation; the depth or this work is admirable.

The problem with the author’s research is that there are no primary sources — in other words, no new interviews with Scott or anyone associated with him or his films. Certainly, he has the reputation of being a deeply private man, so getting an official biographical interview with him may be impossible. There are, however many, many people who know and work with Scott. Some are lengthily quoted from secondary sources, yet it appears that LoBrutto sought out no unpublished material.

Examples of such collaborators include cinematographer, Steven Poster, ASC, a voluble interviewee who did additional photography on Blade Runner (1982) and was director of photography on Scott’s Someone to Watch Over Me (1987). He is mentioned, but neither he nor any cinematographer is interviewed. On The Duellists (1977), Pamela Power worked with Scott to edit one half the picture, while Michael Bradsell edited the other half and received the credit of supervising editor, as the director went back and forth from one editor to the other. As Scott’s first feature film following his highly successful career in television commercials, The Duellists was his effort at breaking out of the demands of a TV spot. LoBrutto quotes Scott in an interview that appeared on Flickeringmyth.com, saying, “The editors gave me a perspective on pace and kept me from falling into a standard commercial director’s trap — that is, from feeling that you have to have a payoff every 30 or 60 seconds.” Unfortunately there is not a proper footnote for this quotation, and the editors involved are not mentioned anywhere else.

There are also annoying errors in the book, beginning with titling it “A Biography.” The bare facts of Scott’s life are presented, but this is a career overview, not an examination of personal triumphs and tragedies, friendships, romances, marriages or children. Beyond a discussion of Scott’s extensive background in art and design, and a nod to how his early years influenced choices in subject matter, there is very little here that cannot be found online. The possible connections between biographical fact and film fictions that LoBrutto offers can easily be inferred from reading the entry on Ridley Scott in Wikipedia.com or watching online interviews with him.

To write that a man born in England the same year the Nazis invaded Poland, whose father (Colonel Francis Percy Scott) was an officer in the Royal Engineers, and whose much older brother (Frank) served in the British Merchant Navy, was influenced by the workings of war and the military is not a difficult observation. That battles become a theme of this director’s creative output only follows logically.

Mistakes that may seem minor become bothersome in the aggregate. About Blade Runner LoBrutto writes, “Being inducted into the National Registry by the National Film Board of America…” There is no “National Film Board of America” in the US. There is a “National Film Preservation Board,” which recommends (not inducts) films to the Librarian of Congress, who names her 25 selections to the Registry each year. Perhaps a small point, but one that could easily be clarified at www.loc.gov/programs/national-film-preservation-board/film-registry/.

It may be understandable that the author chooses to write out fully the name “Ridley Scott” each time he is mentioned, since there are other Scotts in the business. However, this makes for awkward reading, as do the many very short paragraphs, often about the Scotts’ businesses (with younger brother, the late Tony), that are randomly inserted throughout the text with little cohesion.

Scott’s brother Tony, who followed Ridley into television and commercials, worked with his elder brother as early as the latter’s Royal College of Art thesis film, Boy and Bicycle (1961, released in 1965). Ridley mentored Tony; they collaborated through their various production companies and, according to LoBrutto, spent most of their life in regular contact. He writes, “Throughout their lives they spoke to each other on the phone or in person every day.” No source is provided as proof of this fascinating and intense level of communication, and it is not mentioned until the book discusses Tony’s tragic death.

In Ridley Scott: A Biography, the reader is left in sorting through a great deal of interesting but fragmented information that does not gel into a truly chronological or thematic narrative. The extensive work evident here would have been put to better use in a “References and Resources” book that offers lists and cross-references the many resources that LoBrutto so diligently and excellently collects. Along with a more easily read and complete filmography, and more attention to fact checking, such a volume would be invaluable until an “official” biography with direct access to Scott is published.