by Peter Tonguette

Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) opens with a bang that befits its subject: the Vietnam War. As the Doors’ song “The End” dominates the soundtrack, the screen is overtaken with a fireball engulfing a mass of deep-green trees.

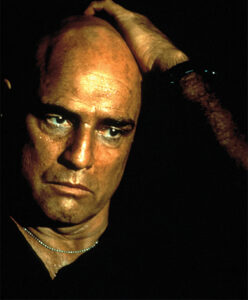

But while Apocalypse Now is set in a jungle battlefield, its actual terrain is the soul of Captain Willard (Martin Sheen). The plot closely tracks the book upon which Coppola and John Milius’ screenplay was inspired, Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness: Willard is directed to ferret out and then “terminate with extreme prejudice” Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), an officer of unsound mind who has stationed himself in Cambodia.

Following the film’s opening shot, we find Willard in a hotel room in Saigon, hungover and disoriented. Amplified by a series of dexterous, intuitive choices in picture and sound editing, the scene illuminates Willard’s inner self. The whirring of a ceiling fan resonates with the force of a helicopter, and dissolves shift from close-ups of Willard to artifacts of his personal life to glimpses of an inferno. In jump cuts, Willard is seen trying out karate-like moves, eventually shattering a mirror.

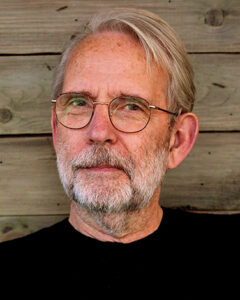

In short, the scene is deeply and profoundly strange — but that was not the original plan. It was August 1977. Coppola and company had recently come home to San Francisco from the Philippines, where the film’s 15-month production had taken place, bringing with them about 1.25 million feet (236 hours) of workprint. Having been engaged to serve as sound designer and re-recording mixer, Walter Murch, ACE, CAS, MPSE, was asked to join the film’s group of picture editors, which included Richard Marks, ACE, Gerald B. Greenberg, ACE, and Dennis Jakob. Marks and Greenberg had already been on the film for about eight months; later, Greenberg and Jakob would depart, and Lisa Fruchtman, ACE, would join the team.

For Apocalypse Now, Coppola envisioned a film that started conventionally and gradually grew “more surreal,” according to Murch. Thus, when the director convened a meeting with the editors to establish who edited what, he doled out assignments on unusual grounds. As Murch recalls: “Francis took us all out to lunch and said, ‘It’s a truth that anyone who works on Apocalypse Now goes crazy, so, of all the people sitting at this table, I’m the craziest because I’ve been working on it the longest. But in terms of editors, there is a progression here, because Walter is the newest, so he’s the least crazy.’”

Thus, Murch was assigned to edit the beginning of the film, from the opening to the famous scene in which a village is decimated as a recording blares Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries”; that scene was previously Greenberg’s responsibility. As Murch remembers it, Coppola said: “I want Walter to edit the first, let’s say, quarter of the film because that’s the most normal, and he’s the most normal.”

When faced with the footage of the opening eight minutes, however, Murch took a different tack. With no script for this scene to guide him, he turned to material not intended to be part of the actual film — including the opening shot and the footage documenting Willard’s drinking and karate moves.

“The slow-motion shot was taken simply to document what is still the largest practical explosion ever set off for a film,” Murch says. “And the drinking/karate scene was an improvisatory acting exercise to help recently hired Martin Sheen get up to speed with Willard’s character. But when Francis saw the dailies of this material, as profoundly different as they were, he felt that they could somehow be woven together into a kind of overture for the film, setting up the subjective intensity of Willard’s state of mind. This was the challenge Francis set for me, the so-called ‘most normal’ of the editors!”

He adds: “You were watching a man who was deep in some kind of nightmare of frustration (what we would now call post-traumatic stress) — not able to fit in back home, and stuck in a shitty hotel room in Saigon far from his goal, which was to get back into action in the jungle.”

What Murch sought — here and elsewhere in the film — was both density and clarity. “I’m always trying to find the balance point between these two contradictory values,” he says. “The audience has to feel, cinematically, the full density and impact of what this guy is experiencing, but at the same time, they have to understand what is going on.”

In total, Murch’s tour of duty on the film lasted almost two years, with his editing responsibility eventually encompassing the film’s first half, up to the sampan massacre scene. Then, in September 1978, he shifted to his original roles as sound designer and re-recording mixer, working in tandem with sound editors Richard Cirincione, Leslie Hodgson, Pat Jackson, Jay Miracle, Leslie Schatz, Maurice Schell, MPSE, and Les Wiggins; and re-recording mixers Richard Beggs, Mark Berger, CAS, Thomas Scott and Dale Strumpell. “It is the longest post-production of any film that I have ever been involved in,” he says.

Production had not been quick and easy, either. The shooting days numbered about 230, Murch says, though he was present for only two of them: a single weekend in March 1977, when he flew in from London for a conference. “I did breathe the air of the Philippine location and catch the mood,” he says. “It was shortly after Marty [Sheen] had had his heart attack, so the situation was fraught, but they were still shooting what they could.” Crises also included Brando’s more-overweight-than-anticipated appearance, a typhoon that took out the sets, and a major piece of recasting, when Harvey Keitel was swapped for Sheen.

“After three weeks or so of shooting, Francis realized that the intense subjectivity of the Willard character did not mesh with Keitel’s active approach,” Murch says. What had been an action- oriented film became more philosophical. “The film was recast with Martin Sheen; a number of key heads of departments left at that point, and a different approach was taken.”

A consequence of these crises: an inordinate amount of film. Due to uncertainty about the film’s ending, no comprehensive first assembly was ever prepared. If one had been, Murch says, “It probably would’ve been six or seven hours long at least.” Murch believes that the “drop-dead length” for most films is approximately 145 minutes, and Apocalypse Now was no different.

So, how to turn six (or seven) hours into two-and-a-half? Adding to the challenge was the hope — still lingering when Murch joined in August 1977 — that the film would be finished by December. Although he doubted that such a quick turnaround was possible, even with four picture editors working at the same time, he told Coppola he felt the only hope of making the deadline with a coherent story was to reintroduce narration spoken by Willard. “John Milius’ original script was written with narration, and the film was shot with that structure,” Murch remembers. “But when I asked about it in August, Francis said, ‘No, there won’t be any narration. We dropped that idea.’”

Taking matters into his own hands — or his own voice — Murch performed and recorded the jettisoned narration (which had not yet been re- written by Michael Herr) and laid it into the film. The results convinced Coppola. “It solved a number of problems that we were going to confront if we didn’t have the narrative voice,” Murch comments. “Willard is the eyes and ears through which you see this world, and as a largely passive lens; he is a silent passenger on the boat for most of the film. So, if you have a lead actor who doesn’t do much and who doesn’t say much, then there didn’t seem, under the circumstances, to be any other expeditious way than the narrative voice to get into what he was thinking.”

The idea solved certain problems, but it only did so much to speed up post-production. December 1977 came and went, and the calendar read August 1978 when Murch began focusing on sound (on which work had been done by others concurrently). Coppola hoped for a revolutionary four-corner, or quadraphonic mix, he remembers, with split surrounds to fly the helicopters around the theatre. But Murch held that a center speaker was needed for the dialogue, for a total of five tracks. “And then Francis said, ‘I also want people to feel the explosions rather than just hear them,’” he recalls. “So, I said, ‘Okay, then we’ll need six channels, because we’ll need a channel for infrasonic sound that will go down below the threshold of hearing.’ We called it six-track. It is now called 5.1 and is the basic standard audio format of the industry.”

Production dialogue and sound were scarce. “The briefing scene when Willard gets his mission is production dialogue, and once you get to the Kurtz compound, most of that is production dialogue,” he remembers. In between, though, “From the time you’re on the boat until the boat stops, I’m guessing 98 percent of it is ADR.”

But Murch embraced the chance to “replace everything.” New helicopter sounds were recorded, and existing library munitions sounds that often dated from the Korean War or earlier were not going to cut it. “Francis wanted the sounds to be accurate, in high-fidelity stereo, and when somebody fired an AK-47, it should be an AK-47 with real bullets in it,” Murch says. “We were able to get hold of these weapons and ammunition, and went to a remote location where we could shoot and do original recordings with all the right perspectives.”

Murch points to the battle on the Do Lung Bridge as the “bending point,” after which the sound becomes less naturalistic. “It starts out with the normal sounds of a battle going on,” he explains. “Then Willard gets off the boat and goes into the trenches and Lance [Sam Bottoms] comes with him, but Lance has dropped acid so, in a sense, we’re hearing the world through Lance’s ears.” Surreal substitutions were made: for example, machine-gun fire became rivet-gun sounds.

In the same scene, the soundscape is emptied with the emergence of a soldier called Roach (Herb Rice). “The idea behind Roach is that he echolocates like a bat; he can know exactly where somebody is by his voice or whatever sound he makes,” Murch says, and the character uses his ability to pinpoint a Vietnamese soldier. “So, at that point, all of the sounds start to disappear one by one, even though the battle is still going on visually, and you start to hear the world selectively, the way Roach hears it.” Viewers, he adds, must be in tune with the film by this point: “We’ve gotten the audience to a strange place where hopefully they’re willing to accept seeing explosions and not hearing them.”

Such an achievement is no less unlikely than a production rife with struggles, and a post- production chock-full of challenges, resulting in a 153-minute masterpiece. But Murch feels the struggles were, in a sense, fitting. “That resonates with the subject matter,” he says, “which is the difficult, difficult, anguished subject matter of American involvement in Vietnam.”