by Michael Kunkes • portraits by John Clifford

Ang Lee laughs! Moviegoers who go to see Taking Woodstock, two-time Oscar-winning director Ang Lee’s new movie expecting another angst-filled tragic romance will be disappointed. Taking Woodstock, which was released in late August by Focus Features, is a light, period ensemble comedy adapted from a memoir by writer/humorist Elliot Tiber, who, in August of 1969, was helping his parents run a dilapidated Catskills hotel, the El Monaco. He introduced the concert promoters, who had just had their permit in nearby Walkill, New York, revoked, to his White Lake neighbor, dairy farmer Max Yasgur, who had some rolling cow pasture to rent—and the rest, as they say, is history.

Taking Woodstock is not about nostalgia for a bygone time; it is not really even about the festival. It is a movie about the transformations that the characters in the cast go through leading up to and during those three days of fun and music 40 years ago. Scored by composer Danny Elfman, Taking Woodstock is two movies, musically. The first third is almost music-free while the film establishes the relationships between Elliot, his parents, the hotel and the townspeople. When music finally does enter the film, it is there to provide a bed of steadily escalating excitement, enhance a sense of place and time, and lend authenticity—much of which is the work of music editor E. Gedney Webb.

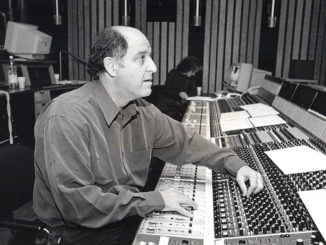

Webb, a musician and occasional composer, has been a music editor for 15 years, dividing his time between both coasts. After working on EDtv for Ron Howard in 1999, he relocated permanently to New York, a move that enabled him to work on both big films, such as Chicago (for which he shared a 2003 Golden Reel Award), The Good Shepherd (2006) and Soul Men (2008), and smaller indies like The Darjeeling Limited (2007) and The Nanny Diaries (2007). “I got a call from the film’s editor, Tim Squyres, because I had worked on Lasse Hallström’s The Hoax (2006), which was edited by Andy Mondshein,” recalls Webb. “That was another era-specific film, which took place in 1971. My musical roots are really in the period from 1962 until 1974; that’s really where the really great American songwriting took place. I read the script and thought it was a very powerful story, so this was a real lucky break for me.”

According to Webb, it was director Lee who largely took the musical lead on Taking Woodstock. “Ang was very specific about the score having a very period sound and style; he wanted it to sound like 1969,” he says. “There is a lot of musical phrasing in today’s pop music that has nothing to do with what music sounded like in the ‘60s, and Ang did not want that to happen; he is very specific about staying true to his vision and that meant staying true to the period—big time.”

Webb adds that composer Elfman was equally devoted to achieving authenticity in his gentle, acoustic score, and had several objectives on the movie. “First, he wanted to nail the acoustics of the era; secondly, since there is very little music in the first part of the film, the score had to provide the energy that would propel the film forward; and his third objective was to really connect and weave together the score and the variations of source music,” Webb reveals. “Even with Danny’s original music, you had to really pay attention to recognize it as a piece of score; he gave it a very organic feel, as if it were an acoustic piece written in 1969 by someone like David Crosby; one that had never been heard before.”

The film also included five era-specific songs––what Lee called “needle drops”––appearing at key points in the story. These included the Grateful Dead’s “China Cat Sunflower,” the Doors’ “Maggie McGill,” Crosby Stills & Nash’s “Wooden Ships,” Blind Faith’s “Can’t Find My Way Home” and Canned Heat’s “Goin’ Up the Country.” “These songs were played as score, because there was no onscreen source,” Webb explains. “I spent a lot of time listening to these songs with scoring mixer and recordist Lawrence Manchester in his studio. When we recorded the material, we could duplicate the original mic’ing as closely as possible and get a similar ‘60s sound without making it sound too current.”

Ultimately, though, Taking Woodstock is a movie of source music—and not just the kind that comes from a radio playing on a tabletop. Designed to blend seamlessly with the needle-drop tunes, a lot of that was provided by the “live” hippies—whether they were gathered on the lawns or swamps of the El Monaco Hotel or hiking along route 17B on the way to the festival. “We came up with a large bed of ‘musical hippie-ness,’ if you will,” Webb recalls. “We recorded all these people with bongos and guitars live, but I wasn’t happy with a lot of the sync, so I went back and re-created a lot of that audio, then cut it to really fit their fingers.”

For example, says Webb, at the end of the “S-Curve” sequence, in which Elliott hitches a ride to the festival on the back of a state trooper’s motorcycle, a musician plays a blues tune sitting on the roof of a car. “With the wild sound that we had, there was no way this guy was playing something bluesy with what his hands were doing, so we re-recorded that and really put it right in his fingers,” he says. “It was also important that the source music should appear to be in the same key as the needle drop, and some of the material was recorded in a key where shifting the pitch would have sounded too weird. If ‘China Cat Sunflower’ was in G and the guy on the car is playing in F sharp, it would have rubbed badly with the outgoing song, so we had to re-record the source in the key of ‘China Cat.’”

The ultimate source music in Taking Woodstock is the festival itself, which Elliot first hears wafting over the hill from Yasgur’s farm. According to Webb, the festival music serves largely as ambience and background, but increases in volume as Elliot gets closer and closer in his repeated attempts to get to the stage. “We tried to present the music in the order in which the acts appeared,” he explains. “At first, we had it mixed too low and preview audiences weren’t picking it up, so we had to do some fixes to raise the levels. Ang wanted people to just go with the flow of the story and the characters as opposed to being conscious of every new piece of music coming from the concert. If you happened to notice that Melanie was singing ‘Beautiful People’ during the scene where Elliot is walking up the hill, great––but the goal was to create a soundtrack and a film for both older and younger audiences.”

Although Taking Woodstock avoids harking back to Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 documentary film, there are a number of pointed homages in which Lee used the iconic split-screen techniques from the original documentary. Webb’s editing played a hand in creating the right tone and catching the right changes in two of those: one when the festival organizers are setting up their offices at the El Monaco, the second as the stage is being assembled.

“For the office scene, I had a Byrds-like 12-string track playing, and the second scene used a Vox organ, California party-like sound,” he explains. “In both scenes, I was trying to capture an energy rather than hitting specific beats. There was so much going on in the split screens, especially in the office scene, that if the music had been louder or more specific, you wouldn’t be able to hear the dialogue. The idea here was to take the emphasis away from the music, but keep the energy level and feel of 1969 present.”

Between score and source music, Webb delivered a total of 36 tracks to the final dub for supervising sound editor/re-recording mixer Eugene Gearty and re-recording mixer Reilly Steele at New York’s Sound One. “I had LCR stems of the whole score and had it split out all the way—multiple acoustic and electric guitars, bass, drums and numerous other tracks for the playback material, both in mono and stereo,” he recalls. “In addition, to emulate ‘60s-style recording, we did a lot of panning back and forth with the lead guitars, something Danny was constantly trying to match in his score. We also did not do a lot of finessing with the source material or spend a lot of time EQ-ing; we wanted to keep the sound close to what we were all used to. We only manipulated things when we needed to, but took some liberties with songs, especially during a long sequence of Elliot’s acid trip with the two hippies in a VW van.”

Summing up, Webb says that the overall role of music in Taking Woodstockwas twofold. “One was the deliberate absence of music to show the isolation of the Catskills in the summer while this family and town wrestle with events; second was how we continually built what became an avalanche of music that took the audience squarely into that era, right to the end of the film,” he explains.

“I think a lot of people are going to go to this film expecting to really hear a lot more music or see another documentary,” Webb continues. “But this is a factual story about a family and how they survive this historic event, which ends up coming into their backyard—literally. Ang’s philosophy was that America lost its innocence at the end of that weekend, and that was the goal we all worked towards.”