by Jack Tucker, ACE

I had the great privilege of meeting and spending some time with the legendary filmmaker Robert Wise. Over the years, I had spoken to him at the American Cinema Editors (ACE) Eddie Awards and other Hollywood events that he attended. He was very gracious to let me question him about films that had inspired me as a youth: The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Helen of Troy (1956) and The Haunting (1963). He shared his memories of the problems he had dealt with in making each of his films. A few years later, when I was the editor of CinemaEditor magazine, I asked him to write an article about the challenge of moving from editing to directing. This he did as a cover story for one of my issues.

Wise was truly a renaissance man of filmmaking. He is known for not pursuing any one genre, having done musicals (West Side Story, The Sound of Music), westerns (Blood on the Moon, Tribute to a Bad Man), science fiction (The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Andromeda Strain), dramas (Executive Suite, I Want To Live!), war movies (Run Silent, Run Deep, Destination Gobi, The Desert Rats), horror movies (The Haunting, Audrey Rose) and epics (The Sand Pebbles, Helen Of Troy). The common denominator of all of these films? They were all crafted by a master storyteller.

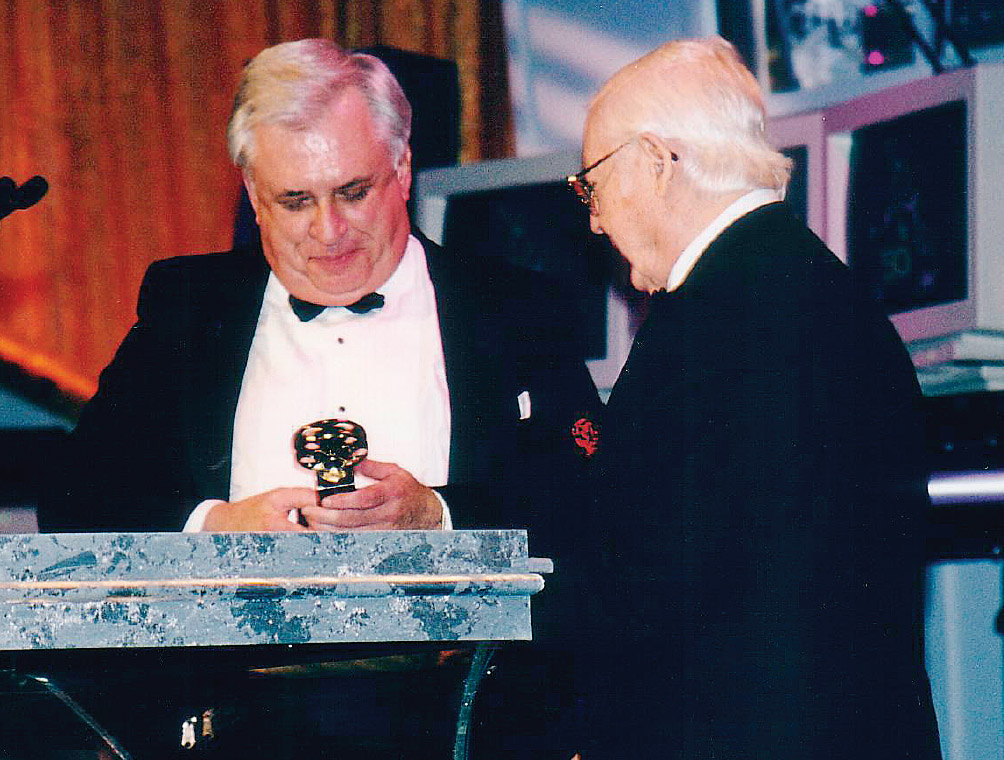

In 2000 I was doubly lucky in getting time to spend with Wise. First, I became the original recipient of ACE’s Robert Wise Award for Promoting the Art and Craft of Film Editing. The Award was conceived by Bonnie Koehler and Dann Cahn; I received it for my work on CinemaEditor. The Award has been given several times since, but I was the only one to receive it directly from the hands of its namesake. It was an inspirational moment for me.

Despite the acclaim Robert Wise achieved as a director, he never forgot his roots in the cutting room.

At about the same time I received a writing assignment to interview Wise. He had just completed his 40th film, a television movie for Showtime Original Pictures called A Storm In Summer (2000). I phoned him at his office and told him what I needed. He said, “Do you want to do this over the phone or do you want to come over to the house?” Of course I jumped at the chance to visit him. “When can I come,” I asked?

We arranged a time and I was there, eager and early. I blurted out, “This is going to be an easy interview. I’m a great fan of yours and I appreciate your extending this time to me to talk about your new movie.” We discussed the film and, since I knew it was his first time working with the new digital technology, I asked him what he thought of the Avid. “It was excellent,” Wise explained. “I found out that if you want to make changes immediately, you don’t have to go back to the Moviola and get the trims out and put it back together. Oh, I thought it was marvelous.”

I pointed out how the Avid had opened the door to increased micromanagement in the cutting room and the concern many editors felt about this. Wise responded, “That’s one of the negatives of it. I think the positives far outweigh the negatives. I feel that not only as a director, but as a former editor. The freedom you get is a big step forward.” He continued: “On A Storm in Summer, I worked with the editor as I always have. I watch his cut and give him notes. Then I leave him alone to do his work.”

At this point I felt confident enough to ask him the big question. “Mr. Wise,” I ventured, “what exactly was Orson Welles’ involvement in the editing of Citizen Kane (1941)?” He replied, “I’d run the rushes with Orson. He’d make his selections as to takes. I’d go back and put the sequence into first cut—a cut that I liked—then show it to him. Then we would have the usual give and take between director and editor: `Why don’t you stay back here a little longer?’ or `Go into the close shots a little later,’ the usual back and forth. That’s the way I worked with Orson. I’ve been asked many times if Orson didn’t come in the editing room and kind of direct the editing. He didn’t at all. I worked with him like I did with any other director and it worked out fine.”

There was always a great humanity in the films of Robert Wise. It came from the man himself.

He also remarked about the growing tendency not to view film on the big screen. “That’s a big mistake; you must see it up on the screen,” he said. “It’s a big difference.” Wise even elaborated about how timing is different on the Moviola than on the big screen. If it’s slow on the Moviola, it’s death on the big screen, he explained, recalling director Richard Wallace’s advice to him when he started directing: “Bobby, just one thing to remember—if it’s slow on the set, it’ll be twice as slow in the projection room.” I asked Wise how he got his start in editing. “I started in studio work in the shipping department of RKO Studios in the summer of 1933,” he said. “I worked my way up through the department as a sound effects editor, a music editor, an assistant editor, and I finally became an editor in 1938.” Who taught him to edit? “Billy Hamilton,” he was quick to acknowledge. “He was a marvelous man and a great editor. Billy taught me. He just brought me along so fast. I think the first picture I did with him was The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939). There was a little sequence of five or six angles, something like that, which I broke down for him. He used to come in and sit at the Moviola and look at the whole thing.

“He said to me, `Why don’t you throw that together? See what you can do with it,'” he continued. “So I stumbled my way through it. He came in and said, `Pretty good,’ and showed me how I could improve it. And within two more pictures, I was doing all the first cutting with him. Finally, I was doing so much of the work that he insisted I share credit with him. Then I went out on my own as an editor. I think the first one I edited on my own was Bachelor Mother (1939).”

I also accused Wise of scaring the hell out of me with The Haunting. “That scene with.,” I started to explain. “.the hands,” he finished for me. “Right,” I responded, “the hands.”

“I’ve had so many people say to me about The Haunting, `Mr. Wise, you scared the dickens out of me and didn’t show anything. How did you do that?’ All by suggestion.”

“Did you learn that from producer Val Lewton, the master of suggestion,” I asked?

“Val always said the greatest fear people have is the fear of the unknown,” Wise explained. Doing The Haunting was kind of a tribute to him because he gave me my break to direct. He was a marvelous man. I adored him.”

After his work on Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Wise was assigned to Lewton’s “B” unit that was making low-budget horror movies. They are considered to this day to be the finest films of the genre ever made. Beginning with Cat People (1942), Lewton produced a series of films done on nearly no budget, utilizing existing sets and noted for their use of suspense over gore to thrill their audience. Wise edited some of them and then moved up in 1944 to direct The Curse of the Cat People when the original director was let go.

Despite the acclaim Wise achieved as a director, he never forgot his roots in the cutting room. He said to me, “I always loved film editing. It’s a marvelous training ground for directors because you come in contact with all aspects of the film. If the company was shooting on the lot, I would go up and visit on the set–a little time in the morning, a little time in the afternoon–and get to know all the people. That’s what happened on The Curse of the Cat People. I knew the actors, I knew the cameraman; so when I had to take over, I knew everybody. I wasn’t going in cold.”

There was always a great humanity in the films of Robert Wise. It came from the man himself. He gave respect to his fellow craftsmen and he learned from them. He was fortunate to be mentored by two great craftsmen: Billy Hamilton and Val Lewton, not to mention Orson Welles and Richard Wallace. He cared about the work that he did and he gave it the reverence it deserved. The proof is in the many films he left behind for generations to discover.