by Rob Feld

While it can be said that many films are made in the editing room, documentaries, by their very nature, almost inevitably are. This can be particularly challenging to film editors when the project seems to have no end point.

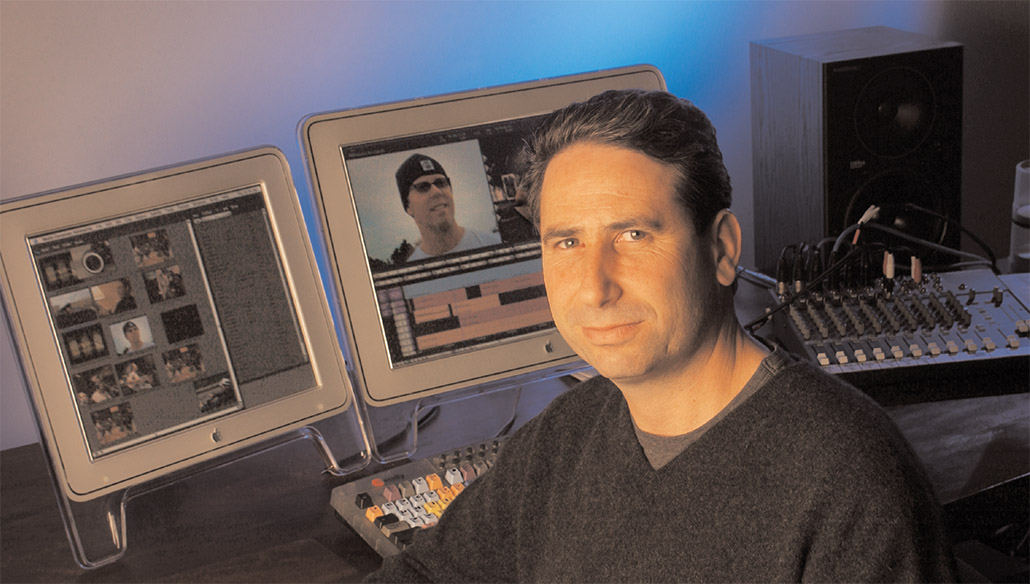

“Who would think it would be two years?” editor David Zieff asks incredulously after the summer release of Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, on which he worked exclusively from start to finish. The doc, directed by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, follows the three-year period during which members of the acclaimed heavy metal band Metallica faced the prospect of a break-up, went through group therapy and saw their lead singer enter rehab, as they simultaneously struggled to record their next album, Saint Anger.

Zieff, whose background includes such television sketch comedy shows as The State, Strangers with Candy and The Upright Citizens Brigade, as well as such documentary work as Michael Moore’s TV Nation and The Awful Truth, had worked with Berlinger and Sinofsky on the 1998 vérité TV doc Where It’s At: The Rolling Stone State of the Union. Zieff continued to collaborate with the directors on a variety of projects, and started working with the footage from Some Kind of Monster shortly after they had begun shooting.

Initially a documentation of the recording of a new album and the band’s therapy process, the project took a traumatic turn when Metallica’s lead singer, James Hetfield, disappeared for 11 months into a rehabilitation clinic for substance abuse, with no guarantee that he was returning to the band. The album, naturally, got put on hold, but the shooting of the doc continued.

“The process of putting a narrative together ultimately became about selecting from 1,600 hours of footage, mired in the minutia of these guys’ lives,” Zieff says. “I contend, on some level, that if you shot 1,600 hours of my boring life and did a bang-up job of editing it, it might actually become a compelling two-hour movie. But if you pick a subject of this kind—and Joe and Bruce have a magic touch for being in the right place at the right time, picking a three-year period which was unsurpassed in the band members’ lives—then you’re certain to be on the right track.

“It was a real challenge to establish and maintain some kind of focus,” he continues. “Nobody really had a sense of where the movie was going at the beginning. It was more a matter of putting together the things that felt right. One of the things we all agreed on––and that I derived from their work in the past––was honesty. Whatever we uncovered, be it ugly, happy, angry or sad, it had to be honest.”

The huge amount of material proved to be a technical obstacle as well. Zieff began editing the digital video (DV) on an Avid System Version 7.1, “which we pretty much blew up with the amount of footage we had,” he remembers. “It got to the point where we couldn’t open the Media Tool. We tried adding a second system to that set-up, and the tech people laughed. We had maybe a terabyte stored at that point. It was insane. PostWorks New York got involved and said, ‘While there may be some good news, we need to talk about the bad.’”

Zieff and his team made the switch to an Avid NT Symphony with a Unity server and spent two weeks re-digitizing around-the-clock on four satellite systems. At the time, the film was slated to be a reality series for Showtime, with multiple editors and systems involved, all linked by Unity. Ultimately, however, the series fell through and the doc continued to be plotted as a movie.

“It was a war of attrition,” Zieff says. “So I created a mantra to guide me: Find things that are self-deprecating. It resonates in a lot of my work. Self-deprecation is funny and human, and always reveals a side of somebody that you don’t normally get in the course of an interview. It translates into moments that are so natural and real that the audience instinctually knows them to be true.

“I wanted it to be entertaining, but I also wanted it to reveal something” – David Zieff

“Lars Ulrich being interrupted by his son, while pontificating about art, was a great moment,” Zieff offers as an example. “I might have cut the scene off at a logical earlier point but a small extension tells you so much more; while his theories on the creation of great artwork and its convergence with metal music may have profound implications, the fact that he’s a dad takes precedence. He can’t escape that.”

For Zieff, finding moments like that one not only would make the film compelling, but would provide him with guideposts as he carved away at the mass of material. “I think I’ve become something of an expert in giant amounts of footage,” he says. “It’s pulling selects, turning them into mini-sequences, mapping those sequences into a structure, and then winnowing down.”

Zieff’s approach differed from that of Berlinger and Sinofsky, who started with a four-hour cut and watched it over and over, winnowing out extraneous scenes and false connections along the way. Zieff, along with editing partners Doug Abel and Miki Milmore, however, preferred coming from the other direction. “We would prefer to put together a two-hour cut in an order that didn’t mislead, using the best scenes and the best connections, and then see what we were missing,” he explains.

This need to compress time created novel approaches to the structuring of the film. Zieff credits Berlinger with one such example: “I had cut a rockin’ four minutes of the Fan Day Jam scene. Doug and I had also cut a lot of material of the so-called “Fuck Meeting,” a heated argument, during which Lars yells the expletive directly in James’ face. Both scenes were important to the film but played rather long until Joe suggested inter-cutting them. The idea allowed us to reduce their length yet maintain their meaty parts, and when the friendly jam and the intense fight were joined, a third story emerged––their public face versus their private face.”

“The process of putting a narrative together ultimately became about selecting from 1,600 hours of footage.” – David Zeiff

Yet another big hurdle Zieff faced was the use of the band’s music in the film. “One of the biggest challenges was trying to use Metallica’s music as the score because it’s not the ideal music to imply deep sensitivity,” he says. “The music is of the power-chugging, blood-curdling, heavy metal genre. It paints with a dark, intestine-eating sort of brush. By carefully utilizing the early stages of their songs and by grabbing some of the musical doodling that goes on between recordings, I was able to score with a light hand at the times it was called for.

“Another challenge was to provide a primer on the complex album creation process and give a taste of all of the songs from the album,” the editor continues. “By parsing each phase of development–– from the initial idea through jamming, lyric writing, vocals, recording, editing and mixing––and applying them to parts of different songs, I was able to give the viewer the sense of having seen the whole process and having heard the whole album. I’m pretty proud of that.”

Zieff also has been very happy with the way in which the film has been received. “Of course I wanted it to be entertaining, but I also wanted it to reveal something honestly,” he says. “One of our main goals was to not make This is Spinal Tap!. It would have been really easy to abuse our access and amuse ourselves by drawing from some obvious similarities to that parody. We wanted to get deeper than that and find some universal meaning in it all.”

And that meaning is?

“Simply the message that it’s okay to go into therapy, no matter who you are, Zieff concludes. “It’s okay to have problems; look yourself in the mirror and deal with them.”