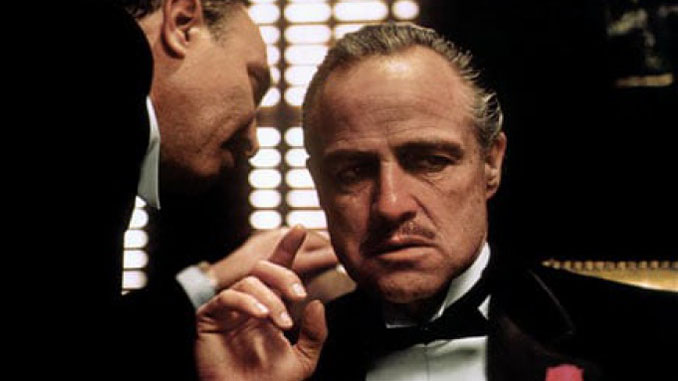

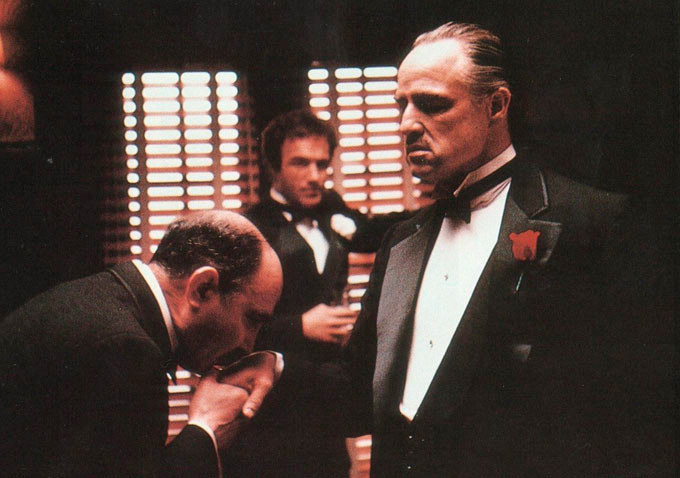

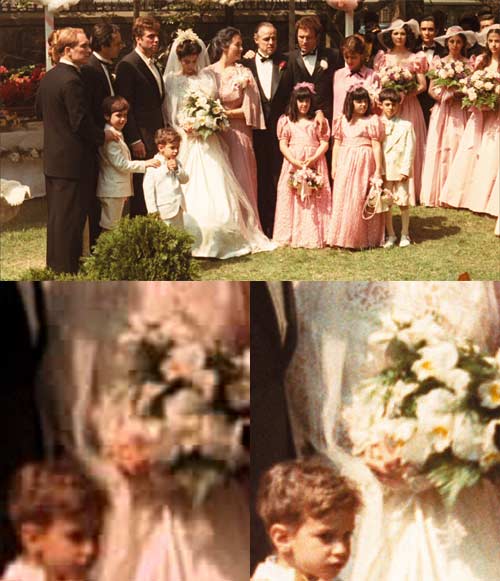

by Peter Tonguette • film stills courtesy of Paramount Pictures

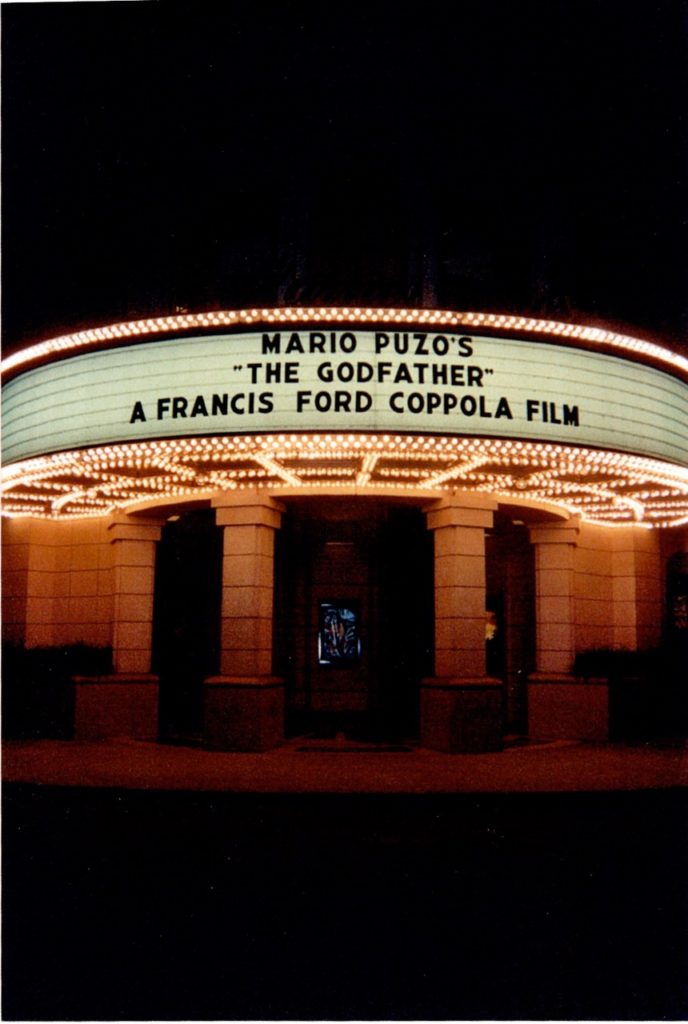

When Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather was released in 1972, the film was celebrated by critics. In The New York Times, for example, Vincent Canby called the frequently beautiful, always intense crime film “one of the most brutal and moving chronicles of American life ever designed within the limits of popular entertainment.”

Audiences were no less adoring. The Paramount release — featuring Marlon Brando, Al Pacino and James Caan as members of an extended family of mafiosi — was the top box office draw of the year, ranking ahead of Ronald Neame’s The Poseidon Adventure and Peter Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc?

Millions may have seen the movie, but, during its initial release, colorist Jan Yarbrough was not among them. “I don’t think I saw it when it came out,” Yarbrough says. “Lots of bits and pieces and scenes, but not the whole and complete and entire movie.”

Three decades after its release, however, Yarbrough was given the opportunity to study The Godfather more closely than any mere audience member. In 2006, the colorist was assigned to work on the restoration of the film at Warner Bros. Motion Picture Imaging in Burbank. Under the leadership of film preservationist Robert A. Harris, Yarbrough helped to restore the richness, depth and texture of the cinematography of Gordon Willis, ASC. As the colorist recounts it, the year-long process was painstaking.

“For a year prior to working on it, we researched and found every piece of image that exists on The Godfather in this world,” Yarbrough recalls. “Every element got inspected and reviewed. We looked at every piece and found the best images we could for every shot.”

A native of Southern California, Yarbrough had the goal of becoming a cinematographer himself when he was young. “I grew up with a father who loved photography, and early on, he put a still camera in my hands,” he explains. “I did a lot of darkroom work for him until college, and always enjoyed working on film prints and creating images. I thought I was going to go in and become a big cinematographer since I knew camera pretty well.”

However, upon entering Los Angeles Valley College, Yarbrough found that there were more opportunities to work with sound than pictures. “A lot of people wanted to become big cinematographers,” he says. “I always liked electronics, and electronics was my minor in school, so I did sound work.”

After transferring to the USC School of Cinematic Arts, from which he graduated in 1974, the colorist-to-be found work as a production sound recordist on independent films and television shows, but soon tired of the instability of freelance gigs. “Student loans came due, and I needed the comfort zone of having a consistent income, so I started looking for an in-house job,” says Yarbrough, who managed to secure a job in the videotape vault at the post-production facility TransAmerican Video (TAV) in Hollywood.

He parlayed the entry-level position into a job as a videotape operator. “I soon learned how to do video through Bill Buck and another mentor colorist by the name of Walt Coleman,” says Yarbrough. After working as a colorist at TAV for several years, he went on to Ruxton Ltd. and Starfax, where he worked on television shows that integrated images shot on film cameras with images from electronic video cameras. “It was all kind of the same thing: color-correction, whether it was on a video image or a film image,” he recalls. “We were taking the wide dynamic range and color palette of negative film and twisting it to match a very limited video image, making it look seamless to the client’s eye.”

For the past 24 years, Yarbrough has hung his shingle at Warner Bros. MPI, where he has worked as a digital intermediate colorist on such major new releases as Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Thirteen (2007) and David Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008). He has also worked on several high-profile restorations of classic films, including John Huston’s The African Queen (1951). “The company’s projects encompass both new films and restorations, but for some reason, all of a sudden word got out and restorations started to happen,” he explains. “And I ended up getting a good portion of them.”

Whether working on a new film, or an old favorite, his job remains the same — or al least similar. “On new films, the DP often doesn’t have time to do what he wants to do on the set, so we, as colorists, end up having to add depth, some shadow work and some highlight work,” Yarbrough reveals. “We have to do that, too, with the old films, but we also have to keep in mind what the original intent of the filmmaker was.”

Yet when Warner Bros. MPI embarked on the task of restoring The Godfather — as well as its acclaimed sequels, The Godfather: Part II (1974) and The Godfather: Part III (1990) — several principal behind-the-scenes artists were available to participate in the restoration process, including Coppola and Willis (who died in 2014).

“It started out as an effort with a lot of hands attached to it, and that always makes it difficult to know what’s what,” Yarbrough confesses. “In the beginning, they had invited the original timer, and they also brought in Allen Daviau, ASC, the well-known cinematographer.” He found the artists’ input to be valuable, but in the final analysis, he trusted what he found on film. “I’ve dealt with negatives since the age of five,” he says. “And I know what a negative is and isn’t telling me.”

In the case of The Godfather, the negative had mostly bad news to communicate to the colorist. “The Godfather is probably the Paramount movie, and from the beginning, requests would come from VIPs for a print to view at their homes,” Yarbrough relates. “Instead of sending a print that was already in the vault, common practice at the major studios was to create a new one-off print each time from the original camera negative. The negative over time accumulated an abnormal amount of damage that comes with a lot of physical handling and running on high-speed printing machines.”

Given the negative’s precarious state, Paramount undertook a search for everything from interpositives to prints to find the best versions of specific scenes or even individual shots. “We ended up replacing or piecing together 70 percent of the original camera negative,” Yarbrough comments. “A lot of our time was spent picking the right pieces, putting them in and making sure that it all flowed and worked properly.”

For some shots, the team retained some sections of the negative but had to add material from a different source for other sections. “We started noticing certain parts where they may have spliced in a few frames of a dupe neg to cover up previous breakage,” the colorist recalls. “There were a couple of shots where we actually took a portion of a frame from a different source and put that in to replace something that was, say, torn badly.”

During one particularly challenging shot featuring the exterior of a church, the right side of the frame was damaged, necessitating the addition of a different element. “With the kind of shrinkage that every film element goes through, I was able to take it, twist the geometry a bit and get the color to the point where the whole section was just beautifully matched,” Yarbrough remembers. “Things like that are just fun to do — and a good challenge. They’re a great reward when you can get them to look right.”

He also had to reckon with the characteristically dark cinematography of Willis, recalling, “Gordon had a different way of using a light meter. He purposely underexposed.” By the time Yarbrough encountered the negative, however, its individual organic color dye layers had begun to fade unevenly. “We were starting with an underexposed negative to begin with, and now had to deal with all of the deteriorating organic issues of an old piece of film,” he says.

Yarbrough used the tools available on the BaseLight color-grading system to retain the film’s deep blacks without shortchanging detail. “You can use one part of it to paint the picture the way you want it, then you can add specific correction layers where you can take the blackest part of the black and actually make it a little more black,” he explains. Black-blacks were a part of Gordon’s color palette.” The colorist also sought to even out — but not eliminate — the grain in the film.

Throughout the restoration, Yarbrough periodically checked in with Willis, who was then based on the East Coast and frowned upon traveling. “We’d send him a cassette every once in a while, have him look at it and then get his comments on it,” says the colorist, who speaks with admiration of the legendary cinematographer. “He had an image, and he knew how to get it. The gentleman was just a genius when it came to images.”

In the end, Yarbrough’s meticulous attention to the palette of The Godfather reaped rewards. In 2008, when the restored trilogy was released on DVD and Blu-ray, New York Times home video columnist Dave Kehr commented, “Mr. Coppola’s three films seem to have reclaimed the golden glow of their original theatrical screenings… The tight grain of the image, so important a component of Mr. Willis’s original low-light photography, has returned to particularly spectacular effect in the four-disc Blu-ray edition.”

“Paramount said it was the film that kicked off the restoration and preservation program at the studio,” says Yarbrough, who has continued to specialize in restorations, armed with tools and approaches he honed on The Godfather.

“I found new ways of doing things on that film that I never would have thought about doing for a good 10 years down the road,” he reflects. “I’m working on a restoration of The Goonies [1985] right now, and using similar techniques as I was back then.”