by Michael Kunkes

Not long ago, the job of recordist conjured up an image of a technician wearing a pair of headphones, listening with intense concentration before a reel-to-reel recorder or wiring up a patch bay. Now, in the present day of ProTools, Ethernet and virtual recorders, one of the oldest technical sound crew positions in the history of production is being severely cut back. Perhaps no other classification in the Guild is so caught in the middle between yesterday and tomorrow, with one foot in the analogue past and the other in the digital present, and a future that is still very much to be determined. The picture is not necessarily bleak, however; the same technologies that have led to cutbacks may also be creating opportunities.

While recordists (who became a part of the Editors Guild in 1998 when post-production members of IATSE Local 695 were transferred to Local 700) have been around since the earliest days of film sound, they have filled so many roles over the years—ADR, Foley, machine room and location sound among others––that a perfectly clear definition of the job has at times become difficult to pin down, with a couple of clear exceptions. The role of the recordist of today breaks down into two main categories: those who work on the dub stage, assisting the re-recording mixers with a variety of tasks; and transfer specialists, who mainly work on format interchange.

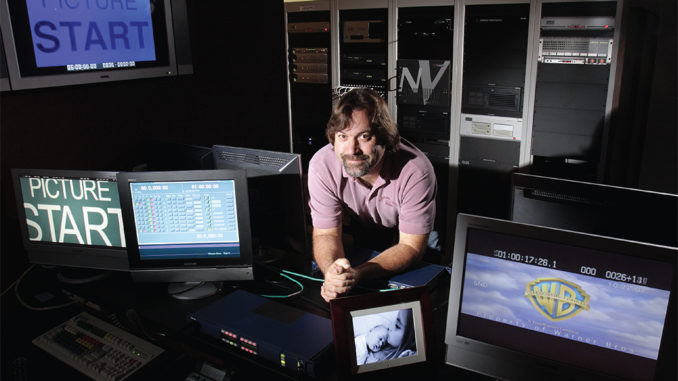

“Fundamentally, our job function has never changed,” says Eric P. Flickinger, a dub stage recordist at Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California. “We need to know what medium our clients are going to be supplying and what they need to walk away with. In this ProTools age, we must be able to take the tracks they are supplying us––be they 35mm mag, old optical tracks, quarter–inch tape or World War II wire recordings––and fit them into the machinery on the dub stage to give them exactly what they need, not just what they think they need.”

Dub stage recordists have to play a lot of roles today. They must be familiar with the console, be able to set up console automation before a session, deal with non-house mixers who may be unfamiliar with the equipment, set up the desk––even answer phones and keep the hospitality fires burning with coffee and snacks. “We are de facto assistant engineers,” adds Flickinger. “We are the first line of defense if engineering is off putting out a fire somewhere else. We troubleshoot the hardware and pass along any problems we find, but engineers do the repairs. That’s a clear distinction that needs to be made.”

John B. Trask, the son of the late production mixer Burdick (Brad) Trask, is a recordist at Universal BluWave Audio in the Digital Mastering Group. According to Trask, the job began to change around 1980, when motion picture and television technologies first began to merge. “Prior to that, it was all 35mm, big-purpose dubbing machines, inter-electrical synchronizers and big analogue recorders,” he says. “Then, audio post for video began to take place in a mixing room environment instead of an online editing bay, and time code and audiotape came together to form the NTSC 59.9 Hz standard, rather than the film world’s 60 Hz. Five years later, the personal computer came along, and people started to explore how they could adapt it for post audio applications. At that point, the rate of change began to accelerate.”

Those changes are still evolving today, as Trask explains. “Everything is gradually being changed over to the digital world, but about 75 percent of what we have is still analogue: 35mm mag, quarter–inch tape, half-inch video and others––called ‘legacy formats.’ It’s amazing how often we go back to the old analogue material, especially when working on foreign titles. We might go through the same show 20 times––for Flemish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Viet-namese, French, Latin Spanish and whatever else is needed. It never stays the same.”

Joe Bosco, another veteran recordist, started out as a loader at Hanna-Barbera in 1977, became a recordist in 1980, and worked at MGM, Universal and Meridien before moving to Disney. When he started on the dub stage, everything was on 35mm soundtracks, he explained, and there were usually three people backing up the mixers—two recordists (one, the “room chief,” in charge of the patch bay, and the other working the recorder) and a loader.

On the looping (now called ADR) stage in those days, there would also be a recordist and a loader, whose job was to run film loops. “It was much tougher back then,” Bosco says. “The ADR recordist start marked and logged every take to 35mm film, reloaded quarter–inch tape every half hour for backup and kept a log, monitored the mix to listen for and report any pops or other anomalies, EQ all the machines and check all the equipment. It would literally take 20 to 30 minutes to set up a two-inch recorder properly. The present is ProTools, and you can set up a 24-track session in two minutes.”

Bosco has a passion for preservation, which continues in his freelance work at DJ Audio in Studio City, California, where he is engaged in a meticulous––and proprietary–– manual process of preserving and digitizing old and deteriorating 35mm film and tape audio masters from major studio clients. According to him, there is a lot less work today for recordists––in part because of changes in the way studios view quality control and technological change.

“Today, management feels that client playback on the stage is QC as far as they’re concerned,” he adds. “They don’t care about making copies and monitoring them today the way they used to with film. Digital is a nice catchword, but unless tracks are converted properly when dropped onto MOs [Magneto Optical drives, such as Sony MiniDiscs], you will get ‘snivets and snats’––little electronic sounds that don’t belong there. It’s just something that sometimes happens in the digital world.”

“The nature of the job makes the recordist a liaison for the physical space,” adds Flickinger, who mainly works with Oscar-winning mixer Doug Hemphill and co-mixer Ron Bartlett on Warner’s Stage 9. “It’s more efficient to keep a person tied to a room and working with one mix team. Even though certain idiosyncrasies of dub stages will be slightly different, studios have designed their facilities to keep things very similar so that we can easily move from room to room.”

Unsun Song is on staff at Universal Studios Sound, working on Mixing Stage 6 with the mix team of Jon Taylor and Christian P. Minkler on recent movies such as Gone Baby Gone, Scary Movie 4 and Babel. Over her career as an ADR, Foley and stage recordist, she has seen a parade of formats—35mm, 24-track analogue, slews of DA-88 machines chained together, and Tascam MMR-8’s, a fixture on most dub stages until just the last year or so—have their day.

“While audio has boiled down to mainly recording and numerous file formats (primarily ProTools in 24-bit .wav), the number of picture formats continue to spiral,” Song says. “As recordists, we’ve had to become a lot more picture-savvy than ever. Picture has become a huge issue with this position in terms of all the different formats that come in and the quality we can achieve once they get digitized. We have to deal with the picture specs in addition to all the audio playback and recording for the stage. Humans are forgiving, but computers are not.”

Trask agrees. “The film world is about sync; if it looks right, it’s fine,” he says. “But with computers, the tolerances are much tighter. I’ll get a six-track dubbed show, and the sync pops will be out of sync by 1/25 of a frame. That’s fine for the dub stage, but not close enough for digital camera standards, so I have to go back and make sure all these elements conform to the standard that’s required for the format, without affecting the actual picture down the line.

“Recordists can troubleshoot and report problems, but they are not supposed to make value judgments and change anything on the audio,” he adds. “A recordist’s concern is that the audio––no matter what the format––conforms to the standard of that format with respect to levels, signal quality and sync. That insures that he passes on the best possible product to the next user, be it editor, mixer or client.”

The recordists interviewed for this story agree that their job has changed radically. Tape machines and patch bays have disappeared entirely from dub stages, and machine room racks now are filled with computers, storage media and routers, not recorders. How has it changed? “That depends on what your perspective on the job was,” responds Flickinger. “If your job was to monitor the tape machine and the repro head, that job’s not there anymore.

Perhaps no other classification in the Guild is so caught in the middle between yesterday and tomorrow, with one foot in the analogue past and the other in the digital present, and a future that is still very much to be determined.

If your job is to make sure the process on the stage is flowing and the clients walk away with what they need, it’s the same job. The tools are just different. You’ve got to deal with the fact that there is no longer any physical media in front of you. You have to be able to understand, organize and distribute data you can’t put your hands on, as well as staying current with technology. In this day and age, there is no room for error as far as losing data goes.”

Marlon Saunders also works as an archival recordist at Sony and, like Trask, is second-generation Hollywood, thanks to his dad, Jim Saunders, a re-recording mixer at Warner Bros. for 30 years, and now a Guild Field Representative. Saunders, who began his career as a Foley recordist, works with a variety of audio––“sometimes even cassette tapes”––and records them into ProTools before placing them on Sony’s server for later repurposing.

“Advancements in technology have caused a lot of the manpower that was once required to become not so necessary,” says Saunders. “In the old days, we’d have to physically place audio mag reels on a cart and wheel them around the lot from destination to destination; now, we are taking ProTools digital files and e-mailing them all over the world. Yes, things have changed.”

“It’s becoming more and more obvious that whoever becomes a recordist will need to have a good working knowledge of ProTools, consoles and signal flow––and also be very organized,” Song explains. “But ultimately, so much of it is about proper communication with the client. It’s not the QC job it used to be, when recordists would sit with their headphones and listen to the mix. Today, we have to deal with so many aspects of the stage operation. The job has grown quite a bit.”

Flickinger feels that at least on the dub stage, the employment picture for recordists is stabilizing. “True, there are no more projectionists, loaders or room chiefs in the machine room,” he concedes. “But at this point, the process fully involves everyone who is still here.”

“It would behoove all of us to not only keep up with, but get ahead of, the technology,” Saunders concludes. “I hope and pray that several of the current recordist positions survive, but if some of them are not around in ten or even five years, I will not be shocked. I’m always looking for opportunities to upgrade my current skills as well as add new skills, so that in the event my current position goes away, I don’t go away with it. That should be the mindset of everyone in this business.”