by Edward Landler

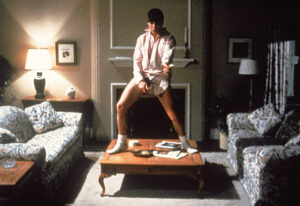

In the summer of 1983, Risky Business opened to healthy box office returns and launched Tom Cruise’s rise to superstar status. Despite respectable reviews, it was pigeonholed at the time as just another of the era’s teen sex comedies stressing raging male hormones. Over the years, however, the satirical bite of writer-director Paul Brickman’s trenchant views on the triumph of material values in the American dream has only become sharper.

The film traces the acceptance of these values over a crucial week in the coming of age of high school senior Joel Goodsen, portrayed by Cruise. With his parents away for a week, he is left on his own in their upper-middle-class suburban house to face two great challenges — getting into Princeton and getting laid. But seeking out prostitutes for sex leads him out of his sheltered world into a spiral of crises that will deeply affect his future actions.

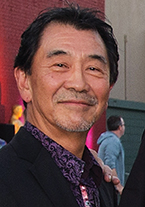

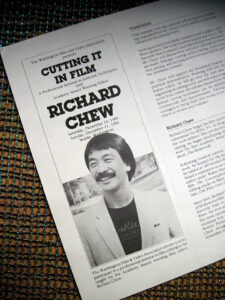

Marking the 30th anniversary of the movie’s release — and reflecting its continuing relevance — the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences included Risky Business in its Oscars Outdoors Summer Series in July, 2013, on the 10,000-square-foot lawn across from the Linwood Dunn Theatre in Hollywood. To introduce the screening, the Academy reunited both cast and crew members, including filmmaker Brickman, producer Jon Avnet, actors Rebecca De Mornay and Richard Masur, music editor Curt Sobel and picture editor Richard Chew, A.C.E.

The film begins with credits over a slow-motion traveling POV across the nighttime Chicago cityscape seen from an elevated train, with its dream-like atmosphere augmented by sound effects and music. The first credit after the main title and the names of leads Cruise and De Mornay reads, “Edited by Richard Chew.” According to Chew, Brickman and Avnet chose this way to acknowledge his contributions to the film before credit placement on features came to be mandated by industry contracts.

Viewing Risky Business confirms that this up- front prominence for the editor credit is more than justified. Enhancing Brickman’s script and blending the cinematography of Bruce Surtees, ASC, and Reynaldo Villalobos, Chew devised a fresh and unique cutting style for personal narrative to bring the viewer into a fluid identification with the film’s protagonist. From the opening dream sequence through Joel’s waking reality, a steady editing rhythm of visuals engages the audience directly in how Joel sees this critical week unfold — just as the process of film editing itself mimics how the mind pieces together its perceptions.

It is no surprise then when speaking affectionately of the movie, Chew notes the great Spanish filmmaker and surrealist Luis Buñuel’s observation: “Fantasy and reality are equally personal and equally felt, so their confusion is a matter of only relative importance.”

Chew, having shared an Oscar for his work on Star Wars (1977), came to Risky Business right after editing his first comedy, Richard Benjamin’s My Favorite Year (1982). About interviewing for the job with Brickman and Avnet, he says, “They liked the feedback I gave about the script and felt I was in sync with Paul’s vision. I was impressed with his naturalistic humor, which did not depend on punch lines. During shooting, I saw how he enhanced his writing by how he composed shots.”

Principal shooting in Chicago took place from July through September of 1982 while Chew was cutting in Los Angeles. As the dailies came in, he realized that a key scene — Joel and Lana, the prostitute played by De Mornay, having sex on the Chicago ‘L’ train — did not convey the sensuality Brickman desired. The footage showed the actors in stylized and passionate — but abstract — poses inside a static train car with a blue screen window.

Chew recalls, “It was arty, cold imagery; not erotic. I suggested that we create a visual metaphor for the sexual climax in the train sequence. To illustrate, I cut together a series of second-unit shots of train exteriors going by from various angles and distances — left, right, left, right — with each getting shorter until we see the spark at the end of the last train shot. I wanted it to feel sexual.”

In the original screenplay, Chew points out, Joel and Lana are described as passing through a station turnstile and the rest of the sequence simply states: “Unrestrained passion against a window of exaggerated romantic imagery (to be devised).” Brickman hadn’t yet thought of how to design the sequence. In the editing room, he liked the visual climax that Chew had created, and began to plan how to add more dramatic foreplay.

During their Christmas break, Brickman wrote new action to fit between Joel and Lana going through the turnstile and the later sequence of train shots Chew had cut together. Then Brickman shot the new scenes on an ‘L’ actually moving through Chicago at night. To heighten the anticipation, the director scattered some passengers around the train car. As they exit at each succeeding stop, Joel and Lana’s passion heats up.

Leading to the act itself, Chew adds, “Paul covered Joel and Lana sparingly — singles on each, some inserts and a side angle two-shot. During editing, we slowed down their movements gradually with each cut as they come together. We used multiple skip-printing to go from normal motion at 24 frames per second to slowing the action to 48 frames per second. In 1983, we had to figure it out on paper. My first assistant editor Howard Heard, now a picture editor, mapped out an optical printing scheme of how to slow the action cut-by-cut until Lana sits on Joel’s lap.”

For the next section where she is on his lap, Brickman wanted to use parts from three different takes but didn’t want jump cuts to join them. Chew remembers, “It dawned on me that since earlier shots had the train lights flickering periodically, I could use short fades to black to join the three shots as if the lights were merely blinking. This way I created the illusion of continuous action.” Building now to both literal and metaphoric climax, the scene finally cuts to the sequence Chew had put together months earlier.

Although music is featured prominently in the film, surprisingly the only music specified in the original script was Jeff Beck’s guitar riff from “The Pump.” The rest of the music came up on the set while shooting or emerged during the editing process.

Choosing Tangerine Dream to compose the main score happened accidentally. Second assistant editor Albert Coleman, now also a picture editor, often listened to the German electronic band in his room next to where Chew was working. The sound of the music caught Brickman’s attention. Chew says, “Paul liked what he heard and replaced the temp music cues with Tangerine Dream cuts. The more we tested them behind our cut scenes,

the more Paul and Jon became convinced that Tangerine Dream should compose our score.”

In the spring of 1983, Brickman, Avnet and music editor Sobel went to Germany where they recorded the score at the band’s studio. They returned with cues designed for specific scenes as well as wild-card “stingers” — short phrases that could be placed anywhere to boost certain scenes.

During final editing, the director, producer and editor all felt they needed a lead-in to Joel’s voiceover describing the opening dream. With the new score establishing a dreamy mood, they wanted a dramatic background for the main credits. “We thought of using the discarded traveling night shots of the Chicago skyline intended for the blue screen background of the erotic train scene. We would now use them as background for the titles,” says Chew.

“I made multiple frames of those moving shots to create a slow-motion effect that would evoke Joel’s emerging sexual desire and foreshadow the train scene later on” he explains. “Coupled with sound effects and music, they became an erotic dramatic device.”

The final cut was finished by the summer of 1983, but a major conflict over the ending of the film surfaced between Brickman and the Geffen Company, which was financing the film. The filmmaker’s ending showed Joel and Lana in a posh restaurant with an emotional distance between them. The company insisted on an upbeat ending that would cut away from the restaurant earlier and show the two on their way to have another night together.

Reluctantly, Brickman agreed to shoot the alternative scene and let test screenings determine which ending to use. Chew says, “At the test previews, the Geffen ending got a slightly higher score and the movie was released with it. Paul was disappointed that his original ending was dropped.” In 2008, a remastered 25th anniversary DVD of the film was released that included both endings and, at the Oscar Outdoors screening this summer, the film was finally shown to a large audience with Brickman’s original ending.

“I’m very proud of my connection with this picture and value dearly the creative collaboration with Paul Brickman and the support of Jon Avnet. You need trusting relationships to make a good film and, in this case, we were all fortunate with the film’s success,” says Chew, who went on to edit Brickman’s Men Don’t Leave in 1990.

Chew concludes, “I’m still friends with Paul. I wish he would have made more films, but at the end of the day, he wasn’t comfortable with the compromises necessary in Hollywood. He’s his own man. That’s why I love him.”