by Peter Tonguette

As a Foley artist, Nancy Parker, MPSE, is tasked with creating the sounds of major life events for characters on-screen. “I go to work and I may perform open-heart surgery, or I may saddle, bridle and ride a horse,” she says. “Every day is different, and coming up with the sounds and the energy for each cue is a rewarding challenge.”

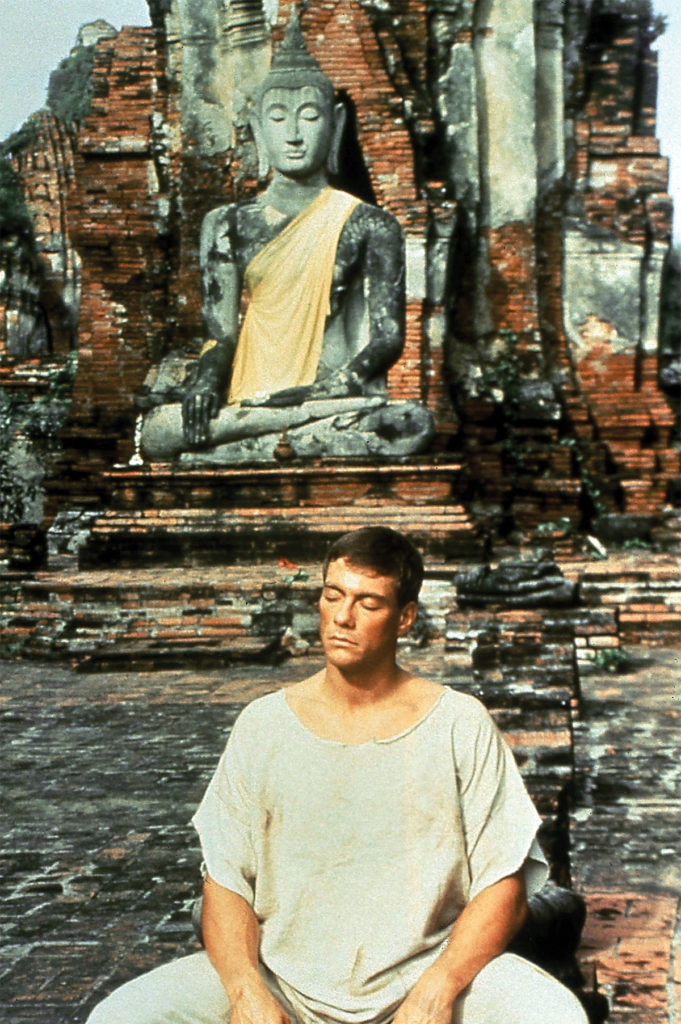

For one of her most significant early films, however, Parker had to ask herself: What does a kickboxing match sound like? In 1989, she was assigned to work with fellow Foley artist James Fisher on the hit film Kickboxer. The globe-trotting action thriller stars martial-arts-maestro-turned-actor Jean-Claude Van Damme as Kurt Sloane, a kickboxing trainer who ends up partaking in the foot-heavy sport himself.

Co-directed by Mark DiSalle and David Worth, the film was successful at the box office when released by the Cannon Group in late summer. After all, remember what John Cusack called kickboxing in Cameron Crowe’s Say Anything… (1989): “the sport of the future.”

In the film, Van Damme did the on-camera kicking and boxing, of course, but to simulate the sounds of the fighting, the production turned to Parker and Fisher — and a side of beef. “We brought it onto the Foley stage for me to hit with my fist, a gloved hand, a stick or a club to create the sounds for the blows to the body,” she remembers. “They would want different things for each part of the body: the shoulder, the chest, the hip, the back. It was fun — and brutal.”

A native of San Gabriel, California, Parker grew up with an interest in fashion. Her mother was the Discovery Charm School instructor at the Sears in Pasadena and head of the department store’s Fashion Team Board. “She’d take me to work and I’d help dress the models for fashion shows and get to do some mannequin modeling,” says the Foley artist, who later found work at a boutique on Rodeo Drive. By then, however, Parker had studied film at Saddleback College and knew she wanted to break into the industry.

“A producer walked into the boutique and instead of saying, ‘Can I help you?,’ I said to him, ‘I want to work in the film business,’” she confesses. “Luckily, he was a producer who introduced me to Dino Conti, Dino De Laurentiis’ right-hand man.” Parker learned that De Laurentiis would soon be producing a remake of John Ford’s The Hurricane (1937) in Bora Bora. “My parents happened to be going to Tahiti on their 25th wedding anniversary,” she says. “I explained to them that I must join them on their trip because I was determined to get a job on the film.” As soon as she arrived, she managed to secure a meeting with De Laurentiis. “He said, ‘I have a lot of problems,’” Parker recounts. “I said, ‘Well, if you have a lot of problems, you need me.’” She joined the film, eventually titled simply Hurricane (1979), as a costumer.

Upon returning to Southern California, Parker began working with Sound Trax, a post-production house run by Jeremy Hoenack. As an account executive, her job was to steer projects to the company, but in the process she received an education in filmmaking. “I was introduced to post-production sound — the sound effects, cut effects, Foley and ADR — in his little studio,” she relates. “He said, ‘This is what we provide on films after principal photography.’”

Parker brought in Mel Damski’s Yellowbeard (1983), a comedy starring Graham Chapman, Peter Boyle and Marty Feldman, and began to learn to do Foley on the swashbuckling film. “I’d have to find props, so I went in my parents’ garage and found a golf ball retriever in my dad’s golf bag, and I used that to help with the telescope,” Parker says.

The experience proved revelatory. Now, when Parker visits a dentist’s office, she listens for the sounds generated by the tools. If she hears the rustling of jewelry on someone nearby, she wonders what kind of bracelet the person is wearing. “I’m always listening,” she comments. “It kind of made it cool for my whole life.”

After leaving that job, Parker ran a casting company in Santa Barbara, and also produced corporate communication films and commercials in San Francisco, but longed to return to the creativity she had found on Foley stages. “I was fortunate to find two Foley artists, Alyson Dee Moore and Patsy Nedd-Doski, who were looking to train someone they could work with,” she explains. “It was just like I struck gold at that point.”

In 1987, she teamed with Moore and Nedd-Doski to work on episodic television and miniseries, including the Western Lonesome Dove (1989) and David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks (1990-91). “We would go to all the great Foley stages all over town — Ryder, Disney, Directors Sound — which we need more of now,” Parker reflects. “We brought our bags of shoes and specialty props. Alyson and Patsy made room for me in the Foley world, for which I am so grateful.”

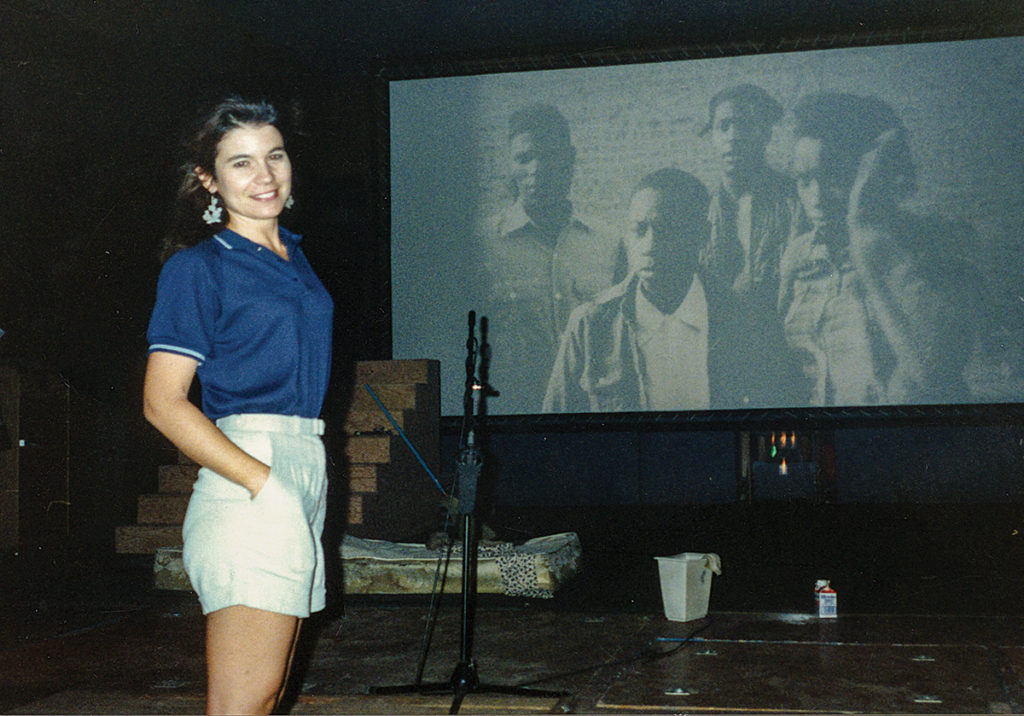

A Mother’s Courage: The Mary Thomas Story.

Yet Van Damme also had a part to play in Parker’s career evolution. After meeting Fisher at Glen Glenn Sound (later Todd-AO), where she, Moore and Nedd-Doski were then working, the Foley artist received the assignment to work on Kickboxer. “I was just a year or two in,” Parker comments. “I was lucky to have the opportunity to work on an action film like Kickboxer.”

During the Foley session on the film, she collaborated for the first time with Foley editor Karola Storr. “We clicked,” Parker recalls. “It was extremely significant to work on that show with her. She was just a champion of Foley in sound.” As Storr sat with the re-recording mixer in a booth, she would use the talkback button to communicate with Parker about the meaning behind a particular cue. “We’d be working on a cue with someone handing money through a jail cell,” the Foley artist says. “Karola would say, ‘Nancy — bribery!’ And I just went, ‘I got it!’ She made it contagious; I just wanted to be really good.”

She and Fisher divided their duties on Kickboxer, but Parker knew she wanted to be responsible for recording many of the body hits. “You kind of split up the characters right down the middle, like, ‘I’ll do that guy and you do him,’” she explains. “But I just wanted to get into the crux of the show and create these sounds. I said, ‘Let me jump in and do those hits; this looks like fun.’”

To help the Foley artist generate the sound of a fist — or, in the case of many scenes in Kickboxer, a foot — hitting skin, a side of beef was needed on the Foley stage. “They would bring it in,” Parker recounts. “Then, of course, you’d have to get fresh meat the next day.” More complex, of course, was deciding the sound of one hit versus another. “The main thing in the movie was kickboxing,” she explains. “So, what does the foot sound like? The foot sounds different than the hand. And are they barefoot? You want to make each sound different so that they are distinguishable: ‘Okay, they just hit his shoulder, so there’s some bone there…’”

Cannon Film Distributors/Photofest

Under the guidance of Storr, with whom she would work on several later projects, Parker walked away from Kickboxer with her eyes — and ears — opened. “Karola focused so much on the nuance and the value of sound, and how it can bring out the character and the story,” she says. “I really thought, ‘I’m not here on the stage. I’m on the screen.’ You have to be that person.”

Even if that meant imitating an action star like Van Damme: “With Jean-Claude Van Damme, you just want to be big,” she comments. “Even though I’m five-foot-nothing, I have to come up with that energy, and I did. There’s a way to do it.”

Although Kickboxer was Parker’s first foray into the action genre, it was not her last. She later served as a Foley artist on such action-driven films as Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003), The Bourne Supremacy and Spider-Man 2 (both 2004). “I always enjoy doing some kind of a tussle, even if it’s not quite the punch but the jerking back and forth,” she explains. “It’s energy, and you get your aggressions out.”

And Parker, whose love of Foley continues on projects at Universal Studios, Warner Bros. and Sony, also made another movie starring Van Damme, 1990’s Death Warrant (collaborating with Foley artist John Post; Storr again was the Foley editor). “That was more of a prison movie, but he’s always fighting,” she says. “I was lucky because Karola worked quite a bit, and having that relationship, she knew what I could handle and was willing to give me those chances.”

Years after both films, Parker met Van Damme face-to-face when she was doing the Foley on an animated project at a studio in Burbank. “He was looping there,” she remembers. “I told him, ‘Oh, we worked on Kickboxer,’ and he said, ‘Oh my God, that’s great!’ I had one of the kneepads that I used to keep my knees protected if I was doing something on the ground, and he signed it for me with a drawing of himself. He’s a pretty good artist.”